Forlag: Pax, Princeton University Press, Pluto Press, Octopus (Norge, USA, Storbritannia, Storbritannia)

(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

When I saw them snow-covered a few years ago The Atlas Mountains from a rooftop in Marrakesh, in the south Morocco, I suddenly came to think of the descriptions of Leo the African (ca. 1485–1554). Or al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan al-Fasi, as he was originally called when he was born in Granada, Spain. Like most Jews and Muslims, he and his family had to flee across the Mediterranean and to Africa when the Inquisition banned them in Catholic Spain from August 1492.

And that was where Leo the African came, to the mountains of present-day Morocco. He began studying in Fez, a little further north, at al-Karaouine University – founded as a madrasa (school) by the Muslim woman Fatima al-Fihri (d. 880) in the year 859. By the time of Leo the Afrikaner, the school had expanded with a library – which is considered to be the world's oldest.

As an adult, he wrote the famous Description of Africa (1526) – which in the following decades was published in Italian, French and English. In the first part of his description of Africa, Leo the Afrikaner depicts precisely these snowy Atlas Mountains, which at their highest point rise more than 4000 meters above sea level.

Profitable books

Now in the 21st century, most people ski there: They rent downhill skis and take the ski lifts to the top before sliding down, as they were on Kvitfjell. But in the 1500th century, Leo told the Afrikaner about how he had enough of surviving when he and some sheep herders had to spend the night in the mountains for three days due to continuous snowfall.

The Edo people built outer walls – four times as extensive as the Great Wall of China.

After this experience, he then depicts, in part 7, his journey south: through the Sahara and further down to the legendary Timbuktu, in present-day Mali. There he discovers that it is books that are the most profitable to trade with: “Here is a great multitude of doctors, judges, priests [imams] and other learned men, who are very well paid by the king. And here manuscripts or written books are brought out from the barbarian states [ed. note: present-day Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia in North Africa], and these books are being sold for more money than any other commodity. "

Leo Afrikaneren here indirectly mentions the Emperor of the Songhai dynasty, Askia Muhammad (1443–1538). Muhammad facilitated education and literacy by supporting the Sankore Madrasa – also known as the "Timbuktu University", founded in the 1300th century.

Mansa Musa

Leo the Afrikaner was not alone in describing the bookstore and the enormous cultural treasures in "Sub-Saharan Africa", as it is called today. In Europe, readers were well acquainted, for example, with the most famous emperor of Mali, Mansa Musa (1280–1337). Money Magazine named Mansa Musa five years ago the richest person in the world: This emperor controlled almost half of the world's available gold deposits, with the gold fields in Bambuk (Senegal) and Bure (southwest of Bamako, on the Mali / Guinea border) – and with access also to gold mining in Lobi (Burkino Faso) and Akan (Ghana / Ivory Coast). When Mansa Musa passed through Cairo on his way to Mecca on a pilgrimage in 1324, he had so much with him gull and wealth that the gold standard in the Mediterranean region was devalued for a decade. No wonder Mansa Musa was drawn in 1375 as the most prominent figure in the world, then raining from the Atlantic Ocean to the Chinese Sea, in the "Catalan Atlas" (Abraham Cresques, Mallorca).

On his way back from Mecca, Mansa Musa bought a huge number of books with him, which led to a new intellectual golden age in the Sahel region. Not only did they import intellektuell to in Mali empire books, they wrote them themselves as well. The scholar Muhammad Baba (d. 1606) wrote about morphology, lexicography, law and poetry – on Arabic. His student Ahmad Baba (1556–1627) wrote no less than sixty works, including on ethics. Baba argued against the slavery of blacks as such. To this day, there are thousands of ancient manuscripts in private homes in Mali and Mauritania – in addition to those in more official collections. Common to the manuscripts is that they are still waiting to be translated and made available to a global audience.

Caravans of Gold

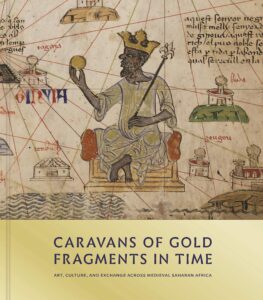

Even more examples of books and intellectual work in West Africa can be found in the new magnificent book Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchanges Across Medieval Saharan Africa (Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University / Princeton University Press). The book is based on an extensive exhibition tour that ended in North America in November 2020. The illustration on the front page is by the aforementioned Mansa Musa, from the aforementioned Catalan atlas.

One of the main points of the book is something I first understood when I sat on the roof terrace in Marrakesh, with a view of the Atlas Mountains in the east and the Sahara desert in the south. I suddenly thought of the journey Leo the Afrikaner made south 500 years ago. Suddenly I realized that there is no abyss between «north of Sahara»And« south of the Sahara »anyway, as our language and our mental divisions of the continent want it to be. In eastern Africa, the meaninglessness of such a dichotomy becomes especially clear, as the Nile's constant movement towards the sea binds the people of the river together from Ethiopia via Sudan to Nubia and Egypt – with the "eastern desert" of the Sahara on both sides.

But also in the western part of the desert this continuous contact between south and north shows itself. Here there is no river, but rather the Sahara which becomes the link. After all, there is a reason why dromedaries are called "the ship of the desert." Tuareg dromedaries as cultural and economic vessels.

Almoravid Empire

One concrete historical example of this connection between south and north of the Sahara is shown by the Almoravid dynasty. This empire was created by the imazigh people ("Berbers") a millennium ago, and the leader Abu Bakr (d. 1087) founded Marrakesh in 1062. At the beginning of the 1100th century ruled AlmoravidEmpire an area from the border with France in the north via Andalucia, in present-day Spain / Portugal, across the Strait of Gibraltar and down the coast and through the desert to the Niger River and the Senegal rivers in the south. In other words, a region of 3000 kilometers in the longitudinal direction, over desert, land, sea and mountains. Both the Mediterranean and the Sahara served here as cultural links.

In a region of 3000 kilometers, both the Mediterranean and the Sahara served as cultural links.

Interestingly, the connections take in Caravans of Gold us even further south than Timbuktu. The book documents the ongoing cultural and economic contact by following the Niger River from Djenne and Timbuktu (in present-day Mali) via the Songhai Empire and down to the Ife and Igbo cultures (present-day Nigeria), near the mouth of the Guinean coast. Half a millennium ago, the Leo Afrikaner knew these areas well: he interestingly portrayed the cultural life also in the caravan city of Agadez (today a UNESCO city in Niger) and Kano in Hausaland (in today's northern Nigeria).

And then we are down by the area of the enough culture, which originated 3500 years ago in central Nigeria, on the east side of the Niger River. Copper mining was initiated nearby (Azelick in Niger) already 1000 years before our era. And there are incredible cultural products enough – the culture can point to from this time – terracotta figures and high quality ceramics. In the book we also see examples from the advanced burning technique with bronze that the igbo-ukwu people created about a millennium ago, based on raw materials in their immediate vicinity.

Recent research shows that the igbos developed their bronzetechnology independent of others – and it is at a more advanced level than was achieved in Europe both before and after. Somewhat later, the igboas of the Ile-Ife Kingdom (Yoruba), on the west side of the Niger River, developed a unique shaping technique from the 1200th century: the faces of various individuals were recreated as portrait sculptures in bronze, or rather brass.

Common to the cultural heritage from both enough, igbo and ile-ife is that it was only around World War II that information about these cultures was "rediscovered" and better known in the world's research environments. At first, European researchers could not believe that such cultural products could arise by themselves in the middle of Nigeria. Yet research is only in its infancy. And it will take a long time to change the general picture of Africa. The continent seems to have been hit by the greatest "cultural lag" of our time, to use William F. Ogburn's term.

Robbery of the British Empire

Another of the river cultures of today Nigeria was the Benin Empire, or Kingdom of Edo – at the mouth of the Benin River, near Niger and the Gulf of Guinea. This empire lasted from the 1100th century until the British in February 1897 burned down Benin city, which should not be confused with the current state of Benin.

A 15-kilometer-long inner wall built of earth and clay surrounded the city center. The Edo people also built outer walls totaling 16 kilometers, 000 times as extensive as the Great Wall of China. The Benin Walls have been named the world's largest modern building by the Guinness Book of Records. When the Portuguese captain Lourenço Pinto arrived in the city of Benin in 4, he wrote that the city “is larger than Lisbon; all the streets are straight and they go as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially the king's house, which is richly decorated and has beautiful columns.

The Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris alone has over 70 African objects, the fewest legally acquired.

Today, this region of Nigeria is perhaps best known for the "Benin Bronzes", the naturalistic bronze and brass statues created from the 1200th century onwards. Due to the British looting in 1897, today an estimated 10 of these works are scattered in 000 different museums, galleries and collections around the world. Dan Hicks, who is an archeology professor at the University of Oxford and curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum. In addition, there are the many unknown private owners of the Benin bronzes. Museums and people in rich countries still make good money on Benin art: Sotheby's in New York, for example, sold a 1600th-century oba bronze head a few years ago for $ 4,7 million. The money went to a gallery in Buffalo, New York.

Benin art is today scattered for all winners. And it's all due to a deliberate and planned robbery by the British Empire in February 1897, just before the celebration of Queen Victoria's 60 years on the throne that summer. As early as the early 1890s, the British had planned to invade the city of Benin. Just before the Victoria anniversary, the British came up with an excuse. They called it all a "punitive expedition." In reality, a systematic looting and burning of the city of Benin took place, which can be equated with the Roman destruction of Carthage in North Africa two thousand years earlier.

All the world's loot

But now it is enough, argues the aforementioned professor Dan Hicks: The world's museums can not live on a life lie, then both they and we rot objection. In November 2020, Hicks came up with a torch of a book: The British Museums. The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution (Pluto Press). The main title is strikingly good: it does not say The British Museum, but The Brutish Museums – «the brutal museums». Because when you walk around "The British Museum" in London, you are just struck by the following: How strikingly little "British" there is to show in the museum. The main part consists of all the world's stolen goods, or objects that one does not quite manage to explain how came into the museum's possession. The Benin bronze is just one of several examples of illegally acquired property. Possibly the museum can be called "The British Booty Museum", the British booty museum.

Hicks is clear on where he stands. His workplace is also the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, which has the world's largest collection of Benin bronzes. Ironically, he himself makes a living from researching the stolen goods from 1897. He then also begins the book by quoting an English translation of the Swedish author Sven Lindqvist's pamphlet "Gräv där du stod" (1978). Dig where you stand. Hicks begins his research and digging where he himself is, at his own workplace.

Hicks argues in the book that it is necessary to relinquish ownership of colonial loot, as has been the case for the last couple of decades with the Nazis' robbery of art into Jewish hands. The Benin Bronze is not "only" a war booty with tens of thousands of cultural treasures, the ship from West Africa and to Europe almost 125 years ago. The Benin bronze is also part of a larger robbery that takes place every day the museums open their exhibitions, Hicks writes.

Cultural History Museum in Oslo

The list of which museums in the world hold parts of the stolen goods – the Benin bronzes – is also listed Ethnographic Museum in Oslo, subject to the University of Oslo. In an appendix to the framework note «Global collective responsibility», to the Ethnographic Museum's board meeting on 17 April 2020, I read that museum director Nielsen in 1920–23 bought Benin bronze figures (head, mask and rooster) from the Umlauf Museum in Hamburg. As if the Germans had legally acquired the art of Benin. According to the museum's own overview, they have only had one changing exhibition of Benin art, in 1952. Clearly it is in Norway as in the rest of the world: Irreplaceable art treasures are stored in basements and warehouses. Not only can you not document that you have obtained the taxes in an honest way, you hide the stolen goods away as well. The Cultural History Museum in Oslo has as many as 55 objects, only a fraction has been made available. The museum does not even show it digitally. On the front page of its website, the museum still writes:

"The growth of the collection was, as in other European countries, greatest at the end of the 1800th century and the first decades of the 1900th century. It was assumed that colonization and industrialization would eradicate much of the world's material diversity, and museums felt the urgency of saving as much as possible. "

Ruled The Ibo People, In Today's Nigeria, 1504-1550 – The Portraits Were Created At That Time)

This is the definition of money laundering. The untruth that African art is safer in Europe than in Africa is not only shown by the fact that European and American museums have sold African art for millions of kroner to private collectors in recent decades. Hundreds of Benin bronzes in Liverpool were bombed to pieces by the Nazi regime during World War II.

Museum of Black Civilizations

Hicks seems to be the first from Oxford University and the Pitt Rivers Museum to make a clear statement. But in France, the debate was raised from the top already in 2017: then President Emmanuel Macron appointed a commission consisting of the experts Felwine Sarr (Senegal) and Bénédicte Savoy (France). Their Sarr-Savoy report came in November 2018, with the English title «The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics». There they argue that the stolen and illegally exported art of colonial times, from which Africa in particular has been affected, must be returned to the countries from which it was taken. At least that the countries are given ownership of their own cultural treasures.

From the middle of the 1600th century, DenmarkNorway began to build forts and colonies on the "Danish Gold Coast". Here, Danes and Norwegians also enslaved 110.000 West Africans.

The new Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar, Senegal, which opened in December 2018, is one example of a new and modern African museum where the objects can be better displayed in their proper element. Many would probably have agreed more that it would have been absurd if the Chinese or Russians had invaded Norway and taken it with them The Oseberg ship, and then exhibited the Viking ship in Moscow or Beijing. This is the reality for African art today: An estimated 95 percent of the preserved art is outside Africa. In the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac in Paris alone, there are over 70 African objects, the fewest legally acquired.

Already a year before the Sarr-Savoy report, President Macron said in a speech at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso: "I can not accept that a large proportion of African countries' cultural heritage is kept in France." He stated that by November 2022 he would facilitate the temporary or permanent return of African cultural heritage to Africa. How much will actually be returned, however, remains to be seen. In December 2020, a decision on return was up for vote in parliament, where a disagreement arose with the Senate.

We'll see how it goes. The bureaucracy is slowly grinding. And a number of European museums fear for their existence – it is as if the lie of life is taken from them. But the debate does not seem to want to go away. Art is art, and theft is theft. Colonization pain, and thus will also real decolonization pain.

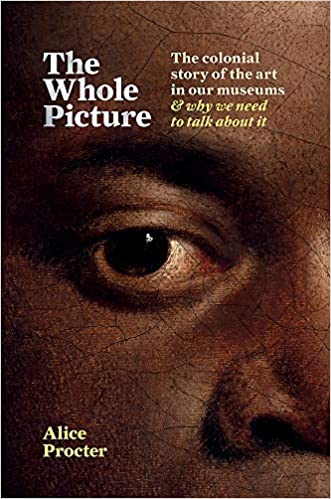

The bread of one is the death of another

At the beginning of 2021 and the new decade, I am also sitting here with last year's book from Australian-British Alice Procter. In recent years, she has arranged "Uncomfortable Art Tours" in London, where she demonstrates the colonial past and the little-told stories, this which the official museums conceal. IN The Whole Picture: The colonial story of the art in our museums & why we need to talk about it (Octopus / Hachette) Procter shows via 22 concrete works how the wounds of the past have not yet healed. Museums' works of art are often both more complex and more contemporary than we realize.

I will think back to my trip to Marrakesh in present-day Morocco – the city that for centuries has been a link between Scandinavia and Timbuktu. The stories about Mansa Musa and all the gold in West Africa did their part so that Norwegians and Danes also sought refuge on the Gold Coast, as the coast outside today's Ghana was aptly called. From the middle of the 1600th century, Denmark-Norway began to build forts and colonies on the "Danish Gold Coast", close to the Akan Goldfields. Danes and Norwegians also made 110 West Africans here slaver, and then send them on ships across the Atlantic to inhuman sugar plantation work on three Danish-Norwegian islands in the Caribbean. History has thus woven a red blood-stained thread from the traditional West African wealth to the newly acquired wealth in Denmark-Norway over the past three centuries. In fact, sometimes the saying goes that one's bread is the other's death.

I'm thinking too Kano and the advanced cultural civilizations along the Niger River down to the Gulf of Guinea in Nigeria. Half a millennium ago, Leo the Afrikaner not only wrote that he was impressed by the abundance of grain, rice and cotton in Kano, in today's Niger. He was just as impressed with the rich merchants and the civilized people. The houses and its walls were built of a type of lime that obviously impressed the visitor from the north. The snow on the Atlas Mountains is still there. But it is preferably the books that call.