(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Recently, I visited my grandmother to say goodbye before traveling with family to settle in the United States for half a year. At one point during our visit, she told me that it could be that she died while we were away. I didn't think about that anymore, because my grandmother occasionally says that she will probably die soon. That her birthday is probably the last. That it's not good to know if she's here next year. But when we gave one last goodbye hug in the door, she began to get water in her eyes, her voice cracked over, and eventually she cried a little. I've never seen my grandmother at 92 years cry before.

In the days that followed, I wondered why she was crying. Was it the idea that we should travel and thus live distant from her for half a year's time? I doubt. Because we don't see each other so much anymore; there can hardly be a greater deprivation. Was it just a real fear of dying that met her at that moment?

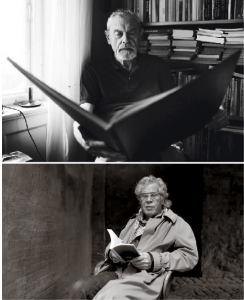

The non-private. That night, as I had said goodbye to my grandmother the other day, I started reading 90-year-old Torben Broström's new work At the edge, which carries the subtitle The memories of another living. The work is certainly also reminiscent of lived life, but it bears only occasional on the personal, anecdotal antithesis. Rather, Broström's book is grounded in his many years of work as a literary critic. Since 1956 Brostøm has been associated with the newspaper Information as a critic, and it is quickly felt that he continues to think, live and use literature daily. Maybe the continuous cultural consumption is the recipe for a long and happy life? However, Brostrøm never gets that explicit. Unlike a lot of the other memorials of the time, Broström's text is apparently non-private. It is only sporadically about Brostrøm himself and almost always about Brostrøm in relation to something other than himself. Especially in relation to the literature, which of course he has dedicated to the love of a lifetime and to the knowledge of a lifetime. Virtually all of the short sections of the memorial volume contain a range of literature from near and far: Montaigne, reflecting on our common notion of life; Rilke's death scenes; Rifbjerg's last words.

The repetition has almost been a working credit with Leth, and with old age it also becomes an existential basic condition.

No red bow. Some sentences have it stuck with one. And while reading Broström's work, I come across a particular phrase that author and physician Tage Voss expressed in an article in Politiken a few years ago. The then 94-year-old Voss said something bastardly in the style of: "There is nothing good about growing old!"

So depressing, Brostrøm expresses himself far from it. Yes, Brostrøm also points out all the flaws with squeaky body, heaviness and the need for rest, but he also has many good things to say about life's closing chapters. The bustle is replaced by a completely different pace that allows you to spot the "irreplaceable value of the moment". How the downy branch of the deer bark invites a friendly touch, or how the beachfront is a universal meeting place where land, water and sky come together.

The book is a collection of sudden whims, detached reflections. Here is no red loop to tie the story of life together and fortunately for it. In this way, Broström's small work finely simulates the existence of arbitrary events and fragmentary nature.

Leth lives. The feeling of being in the company of a literary mosaic reverberates in another aging person's recent writing, Jørgen Leth's text collection But I'm here, after all. Whether the age of the mere 80-year-old birth has freed up time, as it seems to be at Brostrøm, is hardly the case, because Leth has continued on many projects. There are both the poems, the films, the Tour-de-France comments, the lyrical performances and of course the whole Latvian way of life: opening your eyes, keeping your curiosity and inviting the case within. And then there are the repetitions that do not diminish over the years. The repetition has almost been a working credit with Leth and with old age it also becomes an existential basic condition. Now Leth can rightly consider and rethink whether he is bothering to get up. Should I do something? Should I go out or stay inside? It might sound like this:

Leth lives. The feeling of being in the company of a literary mosaic reverberates in another aging person's recent writing, Jørgen Leth's text collection But I'm here, after all. Whether the age of the mere 80-year-old birth has freed up time, as it seems to be at Brostrøm, is hardly the case, because Leth has continued on many projects. There are both the poems, the films, the Tour-de-France comments, the lyrical performances and of course the whole Latvian way of life: opening your eyes, keeping your curiosity and inviting the case within. And then there are the repetitions that do not diminish over the years. The repetition has almost been a working credit with Leth and with old age it also becomes an existential basic condition. Now Leth can rightly consider and rethink whether he is bothering to get up. Should I do something? Should I go out or stay inside? It might sound like this:

“Now it is 10.45 and I have just been sitting and sleeping over the computer. Do not bother to go out. Don't bother staying here. 10.49: the same. Have slept again. Notice I'm getting dressed to go out. But do not bother. Daylight filtered into gray film. Drink some water from small green plastic cup. The time now is 10.56. I'm sitting here. Thinking of getting up and going out. My left hand rested a moment ago heavily on the keyboard. Now no more. It's 10.59. "

Life itself. It's about living life. How life is lived and how it is studied. What you see when you open your eyes and observe life. But Leth is not merely observant. He is also a participant. He constantly produces thoughts and words, and he acts. At the same time, observation itself is part of production because it becomes the focal point of a text like this.

As such, old age is not the central theme of Leth. But, of course, age comes along as an indispensable shadow in life. One can easily read age into the text and sit and find traces of what age does by Leth. How he fears falling as he walks up a hill. How it works in the thighs. But I'm not sure it will make the text better. So I choose not to. Instead, we should probably stick to life itself. Leth is angry in the morning. He is not much for the empty day. All the options and choices. But once the coffee is consumed and individual actions begin to give the day content, the mood rises. Leth is still alive.