(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

The story begins quite dramatically on the plateau of Tibet, where an unusually bad warning causes the enthusiastic cries of monks and pilgrims to be silenced. "This has never happened before," says Erika Fatland's local guide stunned.

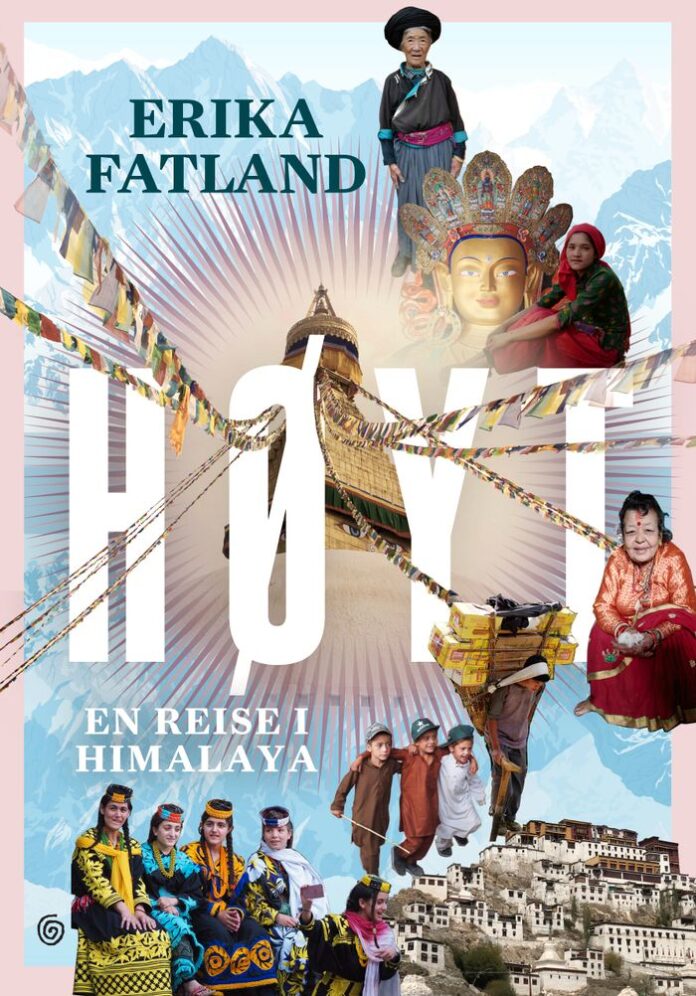

This is not where Fatland's travels begin, but this is where the story in Loud. A Journey in the Himalayas opens. Over more than 600 pages, we are taken from Kashgar to Lahore to Yunnan, across the fabled mountain range with its numerous peoples and customs living under the pressure of international conflicts, unpredictable climate, national ambitions, mass tourism and technological change.

The Kashgar Chapter

"Where does a mountain, a mountain range, a journey begin and end?" Fatland asks initially, and while Morgenbladet's reviewer believes that the question is not perceived as very urgent, the author uses it giftedly to describe the complexity of the Himalayas from geological and geopolitical perspectives as an entrance to understand the whole following travelogue.

"No matter what definition you choose, no one will claim that Himalayas begins in the ancient Silk Road city of Kashgar in the Chinese province of Xinjiang, ”as Fatland humorously notes, but it is nonetheless where her journey begins, because Kashgar is where she must seek the magic pass of the Chinese state machinery to travel through the border regions. Even to get into God's house one must have the papers in order, it should soon turn out.

Fatland considers the others, but just as much himself.

The Kashgar chapter is full of whimsical descriptions of China's oppression of the Uighurs and Chinese middle-class tourism in all its absurdity – an absurdity that Fatland nicely describes is the same for any form of mass tourism combined with state chauvinism. High is consistently characterized by precisely this quality: Fatland considers the others, but just as much himself. She observes at once alienated and embodied the places and the people she meets, but without elevating herself to the natural observer, as so many Western adventurers have done. It is a journey where she tries to understand what she sees, but also what she brings.

There are limits…

Unselfishly, she admits on some of the first pages of the book that it was Donald Duck's "many escapades in 'Langvekkistan'" that originally fueled her burning desire to one day go on an expedition in the Himalayas. Fatland has researched extensively and far-reachingly in both historical and current accounts of the places she travels through – and generously shares this knowledge throughout the book – but at the same time recognizes that there are limits to what one as a traveler can understand, no matter how sincere one tries.

"What would I have gotten if I had not known what I knew?" she asks herself in the border town of Kashgar, where she can not talk to the locals without her mere inquiry would put them in danger of the authorities' sanctions, and follows up: «And what got Am I really with me? ”

These are two questions that many a traveler – whether the purpose of the trip is private diversion or of a work nature – should ask themselves, but often neglect. From my own reportage journeys, I know how porous the boundary is between insight and misinterpretation. And that this applies to both places that you know in depth and places that you have very few prerequisites for understanding. Fatland's sincere skepticism about his own ability to combine research, observation, gut feelings and human knowledge is exemplary.

Under cross-pressure from international conflicts, unpredictable climate, national ambitions, mass tourism and technological change.

High is at once impassable like the mountain range itself and easy to read with its wealth of wonderful, disturbing, bizarre and touching little stories in history: Like the stories of and from Western adventurers and colony administrators she has fished out of the archives and weaves into the travelogue. Like the many strange conversations she has with people she meets on her way and with her various interpreters and guides. For example, Ahmed in the village of Odigram in the Pakistani Swat Valley, who turns out to be writing a doctoral dissertation on the Norwegian anthropologist Fredrik Barth. Or the Chinese interpreter Apple, whom Fatland inadvertently gets driven to tears by asking too many questions. About Tibet, about Hong Kong, about equality.

"Why are you asking about all this?" Apple angrily asks back, accusing Fatland of asking about things she already knows the answer to, or about which she already has a clear opinion. Fatland denies that this is her agenda, but one senses that she quietly and between the lines is also considering whether Apple might still have a point.

Travelogues

With High Erika Fatland has shown that travel stories are a genre that can provide real insights – both for the traveler and for the reader. And that it does not have to follow the old colonial schema, where it is given in advance who is watching and who is being observed, although it is still given that only a small minority can make the journey and report on it afterwards, while the vast majority are referred to as the hospitable recipients of people with multiple resources. Nevertheless, it is both an enlightening and literary pleasure to follow Fatland's attempts to get closer to Langvekkistan – still with a child's open mind, but with an adult's analytical abilities.