(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Studies show that modern Iranians are not very diligent book readers. The Internet and smartphones have increasingly removed Iranian readers from the book. Book reading now occupies only 13 minutes of the day for an average Iranian, a range that is alarmingly low. Based on Book House of Iran, the most trusted non-profit organization and source for books and publishing, 7575 book titles were published in May 2017. That is 27 percent less than the year before. After the capital Tehran, it is the two most religious cities in Iran, Khorasan and Qom, which huser most publishers.

This cultural crisis has been debated by cultural workers ever since the Islamic revolution in 1979, when the sharp increase in the population was expected to result in similar growth in book publishing and reading. Many authors blame the economic development and politics of the Islamic Republic, but cultural explanations are probably more obvious: The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance has its policy of removing, adjusting, and modifying parts of books if they believe something is in conflict Islamic values. The red lines are particularly linked to religion, sex, the priesthood and civil liberties that are banned in Iran.

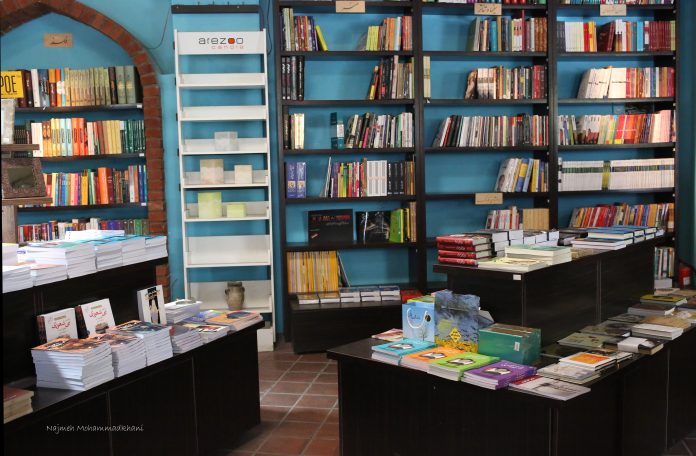

Foreign bestsellers. The Tehran International Book Fair is held annually in May, and is a very important cultural event that attracts crowds of enthusiastic Iranians. This year's fair had half a million visitors every day. However, this overwhelming participation is not a good indication of what the book's terms are in Iran, or with Iranian readers. Visiting the book fair is too much entertainment in itself rather than an opportunity to get acquainted with recent publications.

Concerns in daily life prevent Iranian writers from flourishing.

It is interesting that foreign, translated novels and other books make up the bulk of the bestsellers in the Iranian book market. Foreign authors may appear to be more important and respond better to the taste of Iranian book readers. Last year was the biggest bestseller in Iran Me Before You by Jojo Moyes. In the next two places came Asshole No More, written by Xavier Crement, and The Forty Rules of Love: A Novel of Rumi by Elif Shafak. Iranian lyricist and storyteller Mohammad Kazem Akbariani believes that Japanese Haruki Murakami is more popular than the country's own writers among Iranian readers. The reason he believes is the weakness and lack of creativity of Iranian writers rather than the weakness of Iranian readers. According to him, the concerns of daily life prevent Iranian writers from flourishing. Not many people have writing as their main job.

In an interview with Alef news channel, Iranian sociologist Masoud Farasatkhah described the various causes of the book crisis. He believes that the book has been downgraded to just one object, a commodity and an industry, and is not seen as a source of knowledge and recognition. It is degraded as an individual commodity rather than a collective mental resource. Today, books are unable to play a role in the collective spiritual sphere. Many book publishers affiliated with the government enjoy special privileges, and publish books to gain recognition.

In order to improve the conditions for books and reading in Iran, it is crucial that the policy of monitoring and censorship change.

Farasatkhah is completely in line with other sociologists and cultural workers who claim that the poor living conditions are one of the most effectively weakening the book's status in Iran. For example, the growing poverty among the Iranian middle class is a major contributor to reducing the book's position. Farasatkhah also clearly states that it is the government's policies, legislation and guidelines that contribute most to the crisis of the written word. Censorship and government authority make the book market poorer. He also noted that many of the books on the market have been translated, revealing distrust of Iran's own authors.

Impatient readers. As smartphones have become more common, Iranians spend far more time than ever in an endless world of free-flowing information and data. Recent statistics show that Iranians spend between five and nine hours each day in cyberspace via their smartphones, and the average Iranian owns one and a half mobile phones. This, of course, has made it more difficult for Iranians to devote much time to books. A wide range of varied information is easily accessible at the touch of a button; information that is abbreviated and compact, an abundance of entertainment and fast accessibility. This increases the distance between books and the everyday life of impatient readers. On the other hand, cyberspace also opened up opportunities for Iranian writers who did not get their books approved by the censorship agencies. In recent years, a large number of unauthorized books have been published online by authors located both outside and within the country's borders.

The book's weak and vulnerable status internally in Iran hinders dynamic international rivalry. Reza Amirkhani, an Iranian novelist, has declared his 15-year struggle to enter the international book market for failure. Amirkhani believes that Iran's breach of the Bern Convention, which is for the protection of literary and artistic works, also harms cultural exchange. This is unfortunate for Iranian writers in the international book market. Iranian author Hossein Sanapour has said that respecting the Bern Convention can help resolve the book crisis in Iran; The turnover of books will then increase, translators will get well paid, and thus the quality of the translations will be better. At the same time, foreign translators will be more willing to translate books from Persian, and this cultural interaction will grow and have a positive impact on the book market in Iran. With today's situation, many publishers and translators are asking for permission from foreign authors to translate and publish their books. For example, Ofoq Publishing acquired its first rights to publish a foreign work in 1997, although strictly not permitted by Iranian law.

The terms of books in Iran have fluctuated with political, economic and cultural changes. It is no secret that a population's reading rate is important for cultural and social development. Reading nations can accelerate their civilization development. Tolerance and mutual understanding are consequences of a high reading rate among the population. In order to improve the conditions for books and reading in Iran, it is crucial that the policy of monitoring and censorship change. It should be removed, or at least made more author-friendly. Iranian media such as television, radio and the press need to pay more attention to culture-building practices, and to inspire and encourage people to read more. Good reading habits need to be internalized early, in schools and kindergartens. Last but not least, reading books should ideally at least replace parts of the web browsing among Iranians, as development and progress never come from unreliable and fake knowledge from applications and social networks. Books are genuine and reliable.