(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Experts on Artificial Intelligence (KI) is mainly divided into two camps: Those who feel confident that machines will pass humans in intelligence in a relatively short time and who fear what consequences this will have for humanity, and those who feel confident that machines can never become more intelligent than us and therefore believe there is little to fear.

Author Melanie Mitchell definitely belongs to the latter category.

Mitchell is a professor of informatics at the University of Portland and has worked with analog thinking, complex systems, genetic algorithms and cellular automata (mathematical modeling). She has several books and publications behind her, among other things An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms (1996). She claims that even though a machine has managed to make itself unbeatable in chess, it does not suffice for anything else.

I think she seems too laid back in her views. It is true that what is easy to learn for humans is difficult for machines, but the opposite also applies. The biggest problem, on the other hand, is that machines and humans have trouble understanding each other. It's hard for us to understand why intelligent machines strive for something that even small children can handle as easily as nothing – such as distinguishing between a dog and a cat in a photo.

We humans tend to overestimate the intelligence of machines and to underestimate them

our own.

Computers are lightning fast to learn the rules of different games, but have great challenges in explaining why they do as they do in a way that we can understand. It's hardly understandable to the machine either. But when we look at how fast computer science has evolved, little can be excluded in the future. The book is far too small about the fusion between man and machine.

Explanation Problem

A person can easily explain why they chose to walk in the park rather than wash the house. But how can a machine explain why it chose a specific feature on the chessboard and not one of the trillion other options? It can't. Nor does it understand that it has won, or what it means to "win". Nor can it enjoy the victory. We can therefore dismiss it as "unintelligent".

But idiots can be more dangerous than smarties. So the fact that a machine is stupid does not prove that it cannot be dangerous in the future.

"I'm terrified. Simply lifesaving. ”Douglas Hofstadter

Since the speed of development has been so enormous in this area, it is of course easy to believe that it involves the machine's rapidly gaining power. Maybe too easy. In the 1980s he became a computer scientist and physicist Douglas Hofstadter asked if he thought a machine could ever become a world champion in chess, which he clearly answered no. When he realized how wrong he had been, the horror took him: In a meeting with Google engineers sometime in the 2000s, Hofstadter said: "I'm terrified. Simply lifesaving. "

Adventurous development

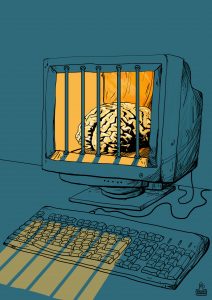

The 1970s development of various machines' skills describes Mitchell as an adventure. Now the adventure has become really in a way that few could imagine, and you can describe this as the relationship between telling an adventure and being part of the adventure itself. Being part of an adventure is probably fun, until you realize that man has the role of Red Hood, while the machine is like the wolf – and that the adventure has actually come true.

Asked: "How scared should we be about KI development?" Mitchell replies: "It's natural to be scared when we watch movies and read science-fiction books about KI development. But this is pure fiction. "

But she also mentions that we are still far from being able to achieve the state of "general artificial intelligence" [systems that can be trained up to virtually anything, ed.], Also called "The Alignment Challenge".

Mitchell is more afraid of stupidity taking over than of intelligence itself. I myself believe that the point is not there, but in what the phenomenon does with us, because whether we call it stupidity or intelligence, it does not matter if the phenomenon threatens our existence.

She answers unequivocally: "In any rate of near-term guesses about AI superintelligence, winning over humans should be far down the list."

Let me just say that an expert like Ray Kurzweil thinks something completely different. For example, Kurzweil predicted (in the book The Age of Intelligent Machines, 1990) that a computer could beat a human being in the future, which happened seven years later when IBM's Deep Blue beat Kasparov, the then world champion at chess.

Fake media

"We need to be aware of the inherent limitations of the new systems, unless we end up overestimating them," Mitchell writes. Although I think Mitchell seems too carefree in terms of how fast machines can evolve and how quickly we can lose control of them, she has many good points. One of the main points is that we humans tend to overestimate the intelligence of machines and to underestimate our own – it is we who are dangerous, not machines. First and foremost, humans should fear their own possibilities, because by the time the machines really get dangerous, it may be too late.

She expresses some concern about how the machines could be used. In particular, she fears the complications of our use of machines within what is called fake media: text, images, audio, and videos that can be manipulated in a way that ordinary people are unable to see.

She also warns against the unethical use of algorithms. Again; primarily we should fear ourselves, not the machines. But the problem is that the boundary between humans and machines is about to be blurred.