(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

The first time I realized the power of documentary film was when I was editing my first film, The Quiet Mutiny. In the comment, I referred to a chicken my crew and I met while patrolling with US soldiers in Vietnam.

"It must be a Vietcong chicken – a communist chicken," said the sergeant. In the report he wrote: "Enemy observed."

The moment of the chicken seemed to emphasize the horror of the war – so I included it in the movie. It may have been unwise. The commercial television regulatory body in the United Kingdom – at that time the Independent Television Authority or ITA – had asked to see my screenplay. What was my source of the chicken's political affiliation, I was asked. Was it really a Communist chicken, or could it have been a pro-American chicken?

Of course, this hesitated for a serious purpose. Then The Quiet Mutiny was shown by ITV in 1970, US Ambassador to the UK, Walter Annenberg, a personal friend of President Richard Nixon, complained to ITA. The complaint did not concern the chicken, but the whole movie. "I intend to inform the White House," the ambassador wrote. Oh my.

The cover story was that the BBC had a responsibility to protect "single elderly people and people with limited mental intelligence".

The Quiet Mutiny revealed that the US forces in Vietnam tore themselves apart. There was open rebellion: summoned crews refused to follow orders and shot their officers in the back or killed them with hand grenades while sleeping.

None of this had been in the news. What that meant was that the war was lost and the messenger was not appreciated.

The head of ITA was Sir Robert Fraser. He contacted Denis Forman, who was then program director at Granada TV, and had an apoplectic seizure. He was scolding, and Sir Robert described me as a "dangerous social enemy."

What worried the ITA boss and the ambassador was the power of a single documentary: the power of facts and the witnesses, especially young soldiers who told the truth and were treated with benevolence by the filmmaker.

The BBC and the government. I was a newspaper journalist. I had never made a movie before, and I was in great debt to Charles Denton, an overflow producer from the BBC, who taught me that facts and evidence right into the camera and to the viewers could certainly be revolutionary.

This undermining of official lies is the strength of the documentary. I have now made 60 films, and I do not think there is any similarity in power in any other medium.

In the 1960s, a brilliantly gifted young filmmaker, Peter Watkins, made The War Game (war game) for the BBC. Watkins reconstructed the aftermath of an imaginary nuclear attack on London.

In the 1960s, a brilliantly gifted young filmmaker, Peter Watkins, made The War Game (war game) for the BBC. Watkins reconstructed the aftermath of an imaginary nuclear attack on London.

The War Game was banned. "The effect of this film," said the BBC, "has been considered too intimidating for the broadcast media." The then chairman of the BBC was Lord Normanbrook, a high-ranking official close to the prime minister. He wrote to his successor, Sir Burke Trend: «The War Game is not a propaganda film: It is intended to present pure facts and is based on thorough research in the official material… but the subject is frightening, and showing the film on television can have a significant impact on the audience's attitudes to the policy of nuclear deterrence. "

In other words, the power of this documentary was to warn people of the real atrocities of nuclear war and to make them question the very existence of nuclear weapons.

Government documents show that the BBC secretly conspired with the government to ban Watkins' film. The cover story was that the BBC had a responsibility to protect "single elderly people and people with limited mental intelligence".

Most of the press swallowed this. The ban on The War Game ended Peter Watkins' career in British television when he was 30. This remarkable filmmaker left the BBC and the United Kingdom, and furiously launched a worldwide campaign against censorship.

Even now disproves Year Zero the myth that the general public does not care, and that those who do are affected by "compassion fatigue".

Telling the truth, and deviating from the official truth, can be risky for a documentary filmmaker.

In 1988, Thames broadcast Television Death on the Rock, a documentary about the war in Northern Ireland. It was a risky and daring measure. Censorship of reports about the so-called Irish Troubles was very extensive, and many of us in the documentary industry were actively warned against making films north of the border with Northern Ireland. If we tried, we were dragged down into a swamp of adaptation.

Journalist Liz Curtis calculated that the BBC had banned, changed or delayed about 50 major television programs about Ireland. There were, of course, honorable exceptions, such as John Ware. Roger Bolton, producer of Death on the Rock, was another. Death on the Rock revealed that the British government sent death squads from SAS abroad against the IRA: They murdered four unarmed people in Gibraltar.

A vicious smear campaign was launched against the film, led by Margaret Thatcher's government and the Murdoch press, especially the Sunday Times, with Andrew Neil as editor.

It was the only documentary that had ever been the subject of public inquiry – and the film's facts were confirmed. Murdoch had to pay damages to one of the film's most important witnesses.

But that did not stop there. Thames Television, one of the most innovative broadcasters in the world, was deprived of its license in the United Kingdom.

Did the Prime Minister demand revenge on ITV and the filmmakers, as she had done with the miners? We do not know. What we do know is that the strength of this one documentary lay in the truth, and that it, like The War Game, marked a highlight in filmed journalism.

Did the Prime Minister demand revenge on ITV and the filmmakers, as she had done with the miners? We do not know. What we do know is that the strength of this one documentary lay in the truth, and that it, like The War Game, marked a highlight in filmed journalism.

The people's medium. I believe that documentaries are spirits of artistic heresy. They are difficult to categorize. They are not like big fiction. They are not like big feature films. Still, they can combine the sheer strength of both.

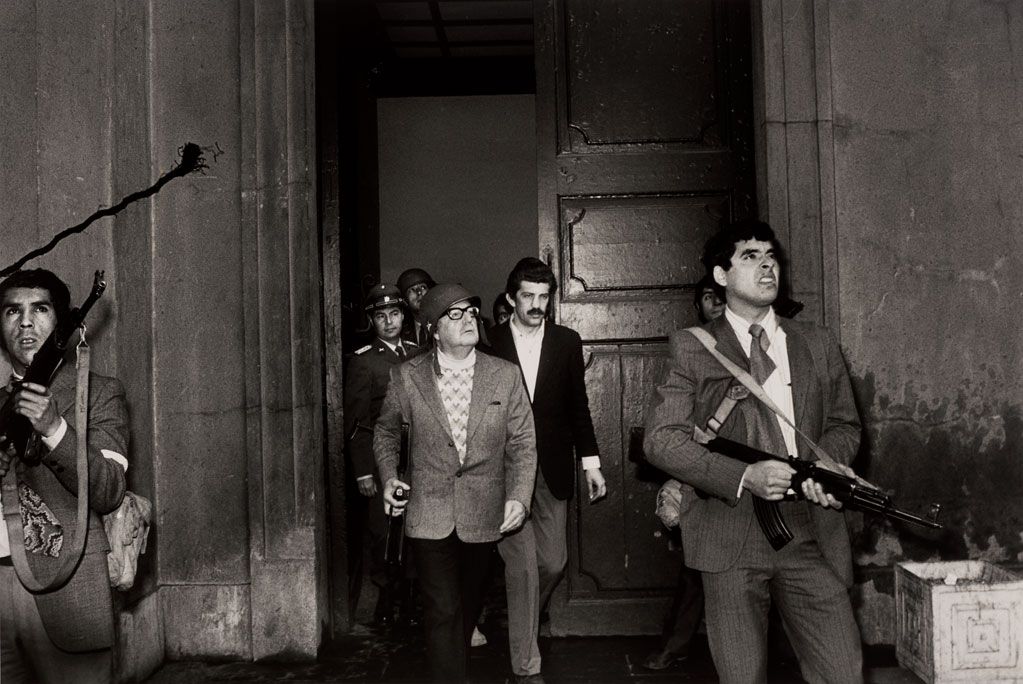

The Battle of Chile: The Struggle Of An Unarmed People is an epic documentary by Patricio Guzmán. It's a very unusual film: in fact, a film trilogy. Released in the 1970s, The New Yorker asked: “How could a team of five people, some with no previous film experience, with one Éclair camera, one Nagra sound recorder and a package of black and white film produce such a significant work? "

Guzmán's documentary is about the fall of democracy in Chile in 1973 by the fascists led by General Pinochet in a coup led by the CIA. Almost everything is filmed with a handheld camera on the shoulder. And remember, this is a movie camera, not a video. You must change the magazine every ten minutes, otherwise the camera will stop and the slightest movement and change of light will affect the image.

I The Battle of Chile there is a scene from the funeral of a naval officer, loyal to President Salvador Allende, who was assassinated by those preparing to destroy Allende's pro – reform government. The camera moves between the military faces: human totem poles with their medals and ribbons, their well-groomed hair and their blurred eyes. The threatening expression on your face tells you that you are about to observe the burial of an entire society: of democracy itself.

A bus driver added his weekly salary. Retirees sent their pension. A single mother sent her savings.

There is a price to pay for filming so boldly. The cameraman, Jorge Müller, was arrested and taken to a torture camp, where he "disappeared" until his grave was found many years later. He turned 27. I honor his memory.

In Britain, John Grierson, Denis Mitchell, Norman Swallow, Richard Cawston, and other filmmakers in the early 20th century pioneered the great class divide and introduced another country. They dared to place cameras and microphones in front of ordinary Britons, and let them speak their own language.

Some say that John Grierson is the one who coined the term "documentary". "Drama is on your doorstep," he said in the 1920s, "where the slums are, where there is malnutrition, wherever there is exploitation and abuse."

These early British filmmakers believed that the documentary should speak from below, not from above: it should be the people's medium, not the authorities'. In other words, it was ordinary people's blood, sweat and tears that gave us the documentary.

Denis Mitchell was famous for his portraits of the working class streets. "Throughout my career, I have been amazed at the quality of people's strength and dignity," he said. When I read these words, I think of the survivors of Grenfell Tower. Most of them are still waiting for new housing, all are still waiting for justice, while the cameras are aimed at the repetitive circus that a royal wedding is.

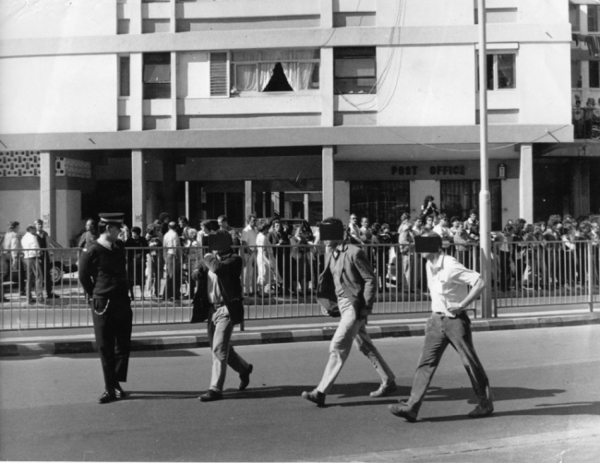

The late David Munro and I made Year Zero: the Silent Death of Cambodia in 1979. This film broke a silence about a country that had been the subject of more than a decade of bombing and genocide, and the strength of the affected millions of ordinary men, women and children in the salvage of a society on the other side of the globe. Even now disproves Year Zero the myth that the general public does not care, and that those who do, are eventually affected by something called "compassion fatigue."

The late David Munro and I made Year Zero: the Silent Death of Cambodia in 1979. This film broke a silence about a country that had been the subject of more than a decade of bombing and genocide, and the strength of the affected millions of ordinary men, women and children in the salvage of a society on the other side of the globe. Even now disproves Year Zero the myth that the general public does not care, and that those who do, are eventually affected by something called "compassion fatigue."

Year Zero was seen by more people than is included in today's hugely popular "reality" program Bake Off. It was shown on mainstream television in more than 30 countries, but not in the United States, where PBS completely rejected it for fear of the reaction of the new Reagan administration, according to one of the directors. In the UK and Australia, it was shown without commercial breaks – the only time, as far as I know, it has happened on commercial television.

After it was shipped in the UK, more than 40 bags of mail arrived at ATV's offices in Birmingham, 26 A-mail letters in the first shipment alone. Remember this was before email and Facebook. In the letters there was one million pounds – mostly in small amounts from those who could least afford to give. "This is for Cambodia," wrote a bus driver who added his weekly salary. Retirees sent their pension. A single mother sent her savings – £ 000. People came to my house with toys and cash, and prayers for Thatcher and indignant poems to Pol Pot and his collaborator, President Richard Nixon, whose bombs had accelerated the fanatic's progress.

The UK is one of the few countries where documentaries are still shown on television at a time when most people are awake.

For the first time, the BBC supported an ITV film. The Blue Peter program asked children to "bring and buy" toys in Oxfam stores across the country. By Christmas time, the children had raised the staggering £ 3. Globally sourced Year Zero weighing over £ 55 million, mostly unsolicited, which brought aid directly to Cambodia: medicines, vaccines and the creation of an entire clothing factory that allowed people to throw away the black uniforms they had been forced to wear by Pol Pot. It was as if the audience had ceased to be spectators and had become participants.

Consumer cult. Something similar happened in the United States when CBS Television aired Edward R. Murrow's film Harvest of Shame in 1960. It was the first time many middle-class Americans saw the extent of poverty among them.

Harvest of Shame is the story of migrant workers in agriculture who were treated almost like slaves. Today, the struggle resonates when migrants and refugees fight for work and security elsewhere in the world. What seems a little special is that the children and grandchildren of some of these people will be subjected to plain treatment and insults from President Trump.

In today's United States, there is no equal to Edward R. Murrow. His eloquent, fearless edition of American journalism has been abolished in the so-called mainstream media, and has sought refuge on the Internet.

The UK is one of the few countries where documentaries are still shown on mainstream television at a time when most people are still awake. But documentaries that go against accepted truths are gradually becoming an endangered species, just when we may need them more than ever.

In poll after poll, when people are asked what they want more of on television, they say documentaries. I do not think they mean a type of program on current issues, which is a platform for politicians and "experts" who try to create a dubious balance between the real power and its victims.

Observational documentaries are popular, but films about airports and emergency police do not make sense to the world. They entertain.

David Attenborough's brilliant programs on the world of nature create an understanding of climate change – most recently.

The BBC's Panorama proves Britain's secret support for jihadism in Syria – somewhat late.

But why is Trump setting fire to the Middle East? Why is the West getting closer to war with Russia and China?

Notice the narrator's words in Peter Watkins' The War Game: «When it comes to almost everything that is about nuclear weapons, there is now practically total silence in the press and on TV. There is hope in any unresolved or unpredictable situation. But is there any real hope in this silence? "

Now this silence is back. It is not considered news that the safeguards against nuclear weapons have been quietly removed, and that the United States now spends $ 4,6 million per hour on nuclear weapons, 24 hours a day, every day. Who knows?

Now this silence is back. It is not considered news that the safeguards against nuclear weapons have been quietly removed, and that the United States now spends $ 4,6 million per hour on nuclear weapons, 24 hours a day, every day. Who knows?

The Coming War on China, which I completed in 2016, has been broadcast in the United Kingdom, but not in the United States – where 90 percent of the population does not know the name or location of the capital of North Korea or can explain why Trump wants to destroy the country. China is next door to North Korea.

According to a "progressive" film distributor in the United States, Americans are only interested in what she calls "character-driven" documentaries. This is a code for a "look at me" consumer cult that devours, terrorizes and exploits so much of our popular culture, while filmmakers are pushed away from a topic that is as intrusively important as anything can be in our modern times.

"When truth is replaced by silence," wrote the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, "silence is a lie."

Every time young documentary filmmakers ask me how they can “make a difference,” I answer that it's really quite simple. They must break the silence.

This is an edited version of a lecture given by John Pilger at the British Library

December 9, 2017 as part of a retrospective festival, "The Power of the Documentary".

It was arranged to mark that the library received Pilger's written archive.