Forlag: (Storbritannien)

(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Once, as a student, I worked on a Danish research project, and when I started, I welcomed the prospect of being integrated into an academic environment with the romanticized ideals that come with it. It was also largely fulfilled until one day I was looking for a colleague's office space. Logically, I went to the institution's info desk and inquired about the location. After a slightly skeptical key behind the screen, I was told that it was not information "just to give anyone." And then the secretary returned to his daily dont. I had entered the institution as an employee, but became a snap to "anyone". After a while I found the department on my own, and here I was met by even more inquiring eyes. Looks that made me think an extra time about the braids that hung along my shoulders and the colorful scarf I had chosen to tie on them that morning. Because if there is something these looks can do, it is to have doubts. Doubt about one's surroundings and doubt one's self. Are you the one who projects? Don't they just know your face? Do they think you're here to clean? I scolded myself for not being prepared. To naively believe that colleges could be anything from a world where the presence of black women is often questioned.

Invisible, but visible

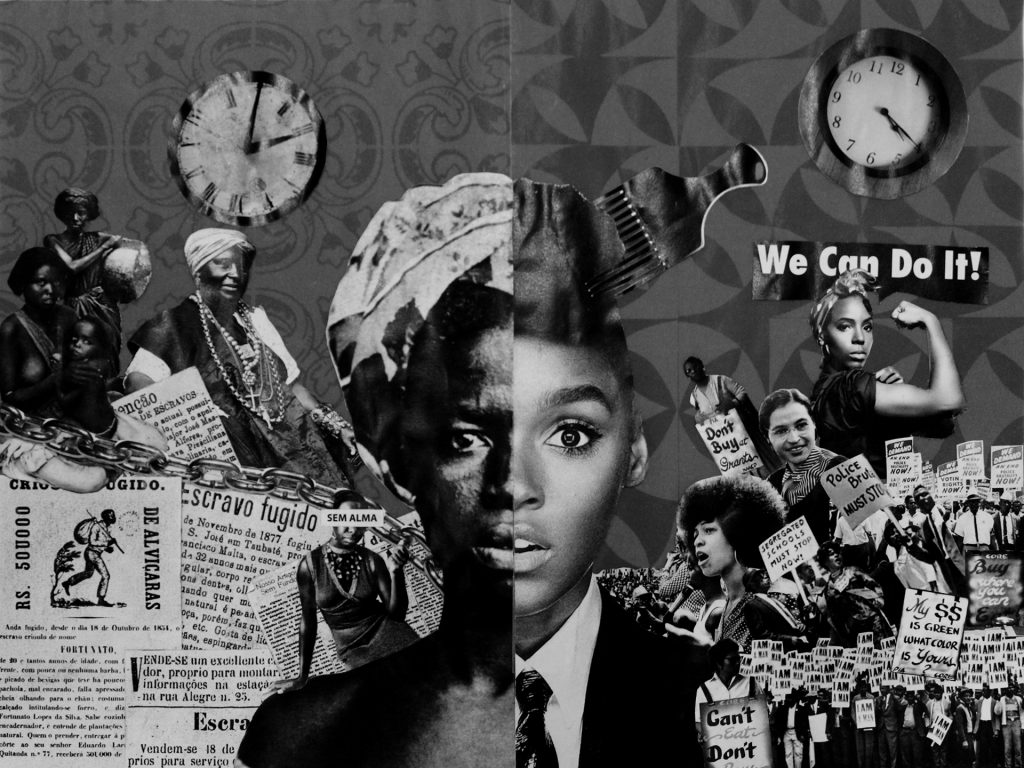

This, of course, is a fraction of the invisibility many people encounter on a daily basis. But one thing is for sure: Black women are getting used from an early age to navigate between an invisibility that blurs them as subjects, and a hyper-visibility that reduces them to objects of other people's stereotypical desires. It is this duality and accompanying alienation that is unfolding in the new anthology, among other things To Exist is To Resist: Black Feminism in Europe.

The anthology is a collection of texts written by individual individuals, political collectives, activists and academics mainly from the African and Caribbean diaspora in ten different European countries. And the show of invisibility and hyper-visibility runs like a thread through the book's 21 contribution. Be it the struggles of African female migrants for rights in Greece, the struggle of black female students for recognition in the Danish academy or digital vulnerability in a time when black pain is becoming more serious. It is also the test of new ideas and the repetition of empowering experiences such as black literary salons in Switzerland, art as recreational healing in Berlin or black feminist film history in England. There are thoughtful discussions about when black separatist spaces are vital to collective healing processes and when broad alliance building is needed. It is evaluative accounts of defeats and victories that humbly nod in recognition of the individuals and movements that were here before and those who are no longer.

"If we black women stay within the existing framework, we will continue to vie for space at the table we were previously excluded from." Chijioke Obasi

The book also contains an interesting critique of US-American political and cultural hegemony, which has also led to the universalization of black US-American feminism in Europe.. "So we read Angela Davis and Kwame Turé, but not Aimé Césaire and Gail Lewis. This gap means a lot for how we think about blackness, solidarity and resistance, ”writes editors Akwugo Emejulu and Francesca Sobande, who see a tendency to erase the experiences of black feminists in a European context. The anthology is thus a reminder of the political and artistic inspirations that various anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles in and outside Europe have embedded in the way black feminism is thought and applied. However, this does not mean that the struggles and ideas of the opposite side of the Atlantic should be ignored – but rather a call for the long-standing silence of black European feminism to cease.

Feminism is a dirty concept

But what is the European black feminism that one finds out has a number of nicknames? The conceptual world is discussed by Chijioke Obasi in the chapter "Africanist Sista-hood in Britain: Creating Our Own Pathways". Why should you stay within the framework of a vocabulary that historically could not contain "your kind"? An ongoing and necessary debate among black feminists, as feminism's liberation project has historically come at the expense of racialized people. This has been seen in feminism's tacit acceptance of racist social structures, the oppression of non-white women, not to mention Nordic feminism's penchant for eugenics. It therefore makes sense that many women from the Global South and in the diaspora have sought other terms. For as Obasi writes: "If we black women stay within the existing framework, we will continue to vie for space at the table we have previously been excluded from."

The use of counter concepts such as Africanist Sista-hood og Womanist thus not only a desire to shake off the exclusion. It is also about recognizing that in the early conceptual universe of white feminism one did not exist at all – neither as women nor as human beings. New conceptions thus also become a way of accentuating the role of black feminism – not as a tributary to original white feminism – but as the source from which much historical and contemporary resistance springs.

To Exist is to Resist is interesting, instructive reading and a well-executed example of how complicated knowledge is easily accessible. None of the lyrics are locked in a self-referencing ivory tower, and what they have in common is that they never get bogged down in abstractions. There is a constant balance between concrete examples, interviews and conversations, and each chapter is equipped with a summary conclusion. In addition, the authors are incredibly aware of their own positions in knowledge creation, and the various forms of cross-pressure people encounter in relation to their ethnicity, gender, class and body capacity. Here, one gets the sense of black feminism in practice: an emancipatory project that is self-reflexive, rooted in practice and explicit in relation to how oppressive structures often overlap and must therefore be counteracted simultaneously.