(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

This is what the Barbican Art Gallery in London aims at by exhibiting "artistic responses to issues such as feminism, climate change and human rights [...] voices that are underrepresented in contemporary art". double exhibition The Art of Change these days show pictures of Dorothea Lange (1895 – 1965) and Vanessa Winship (b. 1960) – both of which focus on people from lower strata, poverty and typical working class. See the post here.

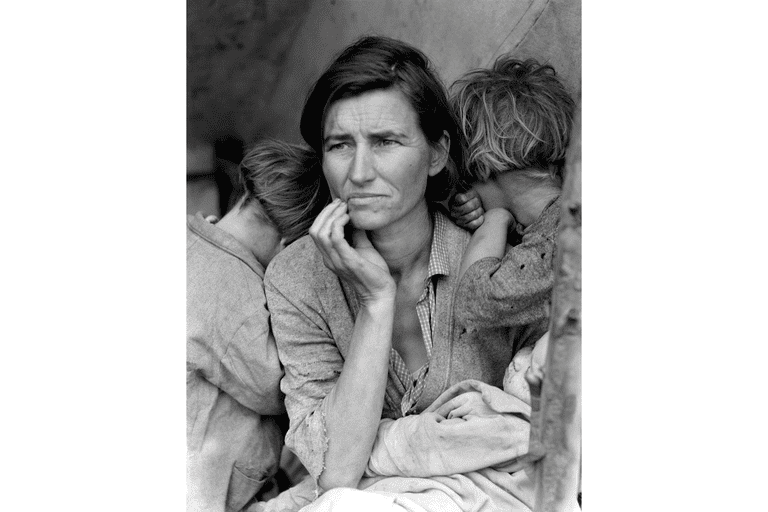

Documentary photography can also be problematic. Long's iconic image of Florence Thompson during the Depression in the United States – at that time the world's most reproduced image – is one example. The Cherokee woman, sitting with her hardened but steadfast expression, impoverished in a refugee camp with her children in 1936, said as 75 year-old in 1978: "That image of me hangs everywhere in the world, but I never got it again." Diary, unlike Lange, writes about the portrayed: "She looked like she knew my pictures could help her, and that's why she helped me. It was a kind of balance between us. "

Socially critical and documentary photography has been of varying importance over time. As critic Susan Sontag described it in On Photography (1977) and Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), it invites "to attention, to reflection". But Sontag has also told her the resentment she felt toward the photograph – not only because the depicted tragedies aroused despair and rage in her, but also because the photographs failed to lead to political action. As the feelings of injustice grow inside us, we also know how powerless we are – how politically paralyzed we really are. Sontag's frustration thus becomes twofold: She feels guilt for the suffering, but also discomfort with her self-centered absence of spirit. As a Western intellectual in reality, she does little to dampen other people's suffering.

Many of us remember Kevin Carter's image of the vulture and the emaciated child from the famine disaster in South Sudan in 1994, an image that is poignant (see above). Carter received the Pulitzer Prize for his photography – but took his life just a few months later. The farewell letter said: "I am haunted by vivid memories – of murder, dead bodies, anger and pain of starving and injured children, of triggerhappy maniacs ..."

But have we also become vultures, insatiable on the misery of others? Sontag describes us as "image-junkies": We crave so intensely for beauty, surface and body, almost like an erotic need. As she writes, 40 years ago – long before the smartphone and Instagram: Are our experiences now only valid if we take pictures of them?

In our culture of likes / dislikes, it is extra important to be aware of the context of an image: For example, is a photo of a crowd with their mobile cameras in the weather, taken from a concert – or simply from a hanging in Tehran? A deeper search into context, Kaja Schjerven Mollerin recently made in the new magazine Pictures: She interprets a photo of Sontag, taken by photographer boyfriend Annie Leibovitz. In the picture we see Sontag walking up the volcano Vesuvius, seemingly unaware that she is being photographed from behind. Mollerin's interpretation is not just the motif of Sontag's own novel The Volcano Lover, where Sontag actually goes in historical tracks. She also interprets the myth of Eurydice being brought back from the realm of the dead – where Orpheus did not have to turn around when he wanted to lose his beloved. Sontag was repeatedly plagued by cancer, from which she eventually died. Which gives Leibowitz's image an extra and dizzying dimension. A successful photograph carries that var that no longer er – life itself in its essence, in its absolute perishability. Instead of consuming snapshots, we can seek an understanding of what an image also hides.

In the future, Ny Tid will devote more space to photography.

World renowned Brazilian documentary photographer Sebastiao Salgado was criticized in The New Yorker in 1991 for aesthetic suffering. Ingrid Sischy writes: “The beauty of tragedy reinforces our passivity to the experiences revealed. Aestheticizing tragedy is the fastest way to stun our emotions. ”Others describe Salgado as far better than more casual colleagues who make human need a consumer product – a source of morbid well-being. There are a number of photographers today who almost "stumble" to horrific and bloody events, and perhaps humiliate the victims rather than Salgado to encourage solidarity, respect and action. For example, only Carter waved the vulture away before jumping aboard a plane and moving on.

In the future, Ny Tid will devote more space to photography. We want form and content – art and politics – to communicate together. We do not think as doctrinally conservative, who reject that politics has anything to do with art, or, as doctrinally radical, who deny that art has anything to do with politics.

Also, documentary photography and film about the suffering of others must not just be about "it concerns the others" and that "fortunately we are not." To look behind the faces of artists such as Lange, Salgado, Carter and Winship show us, the reading of such images must include more than sentimental humanism.