(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

The quotes are from different people I met during my recent trip to Egypt. In January 2011, the Egyptians revolted against Mubarak's repressive regime. The old fear was gone. They no longer had anything to lose – so bad a constitution was landed, and then accidentally hit the regime. Six years later, fear has returned, stronger than ever. Now people are talking about the low-voice regime as they look over their shoulder. Someone doesn't dare to meet me at all.

Five years have passed since I last left Egypt. At that time, the country was nearing the end of a one-year revolutionary era. When I left, Cairo was characterized by protests. Football supporters had lost over 70 of their own in an attack following a match between Cairo Ahly and Port Said. Like so much else, this event was also marked by the political fronts; the supporters of Ultras Ahlawy had been very active in the demonstrations against Mubarak and later against the military council. Many believed the attack was staged by former regime figures seeking revenge.

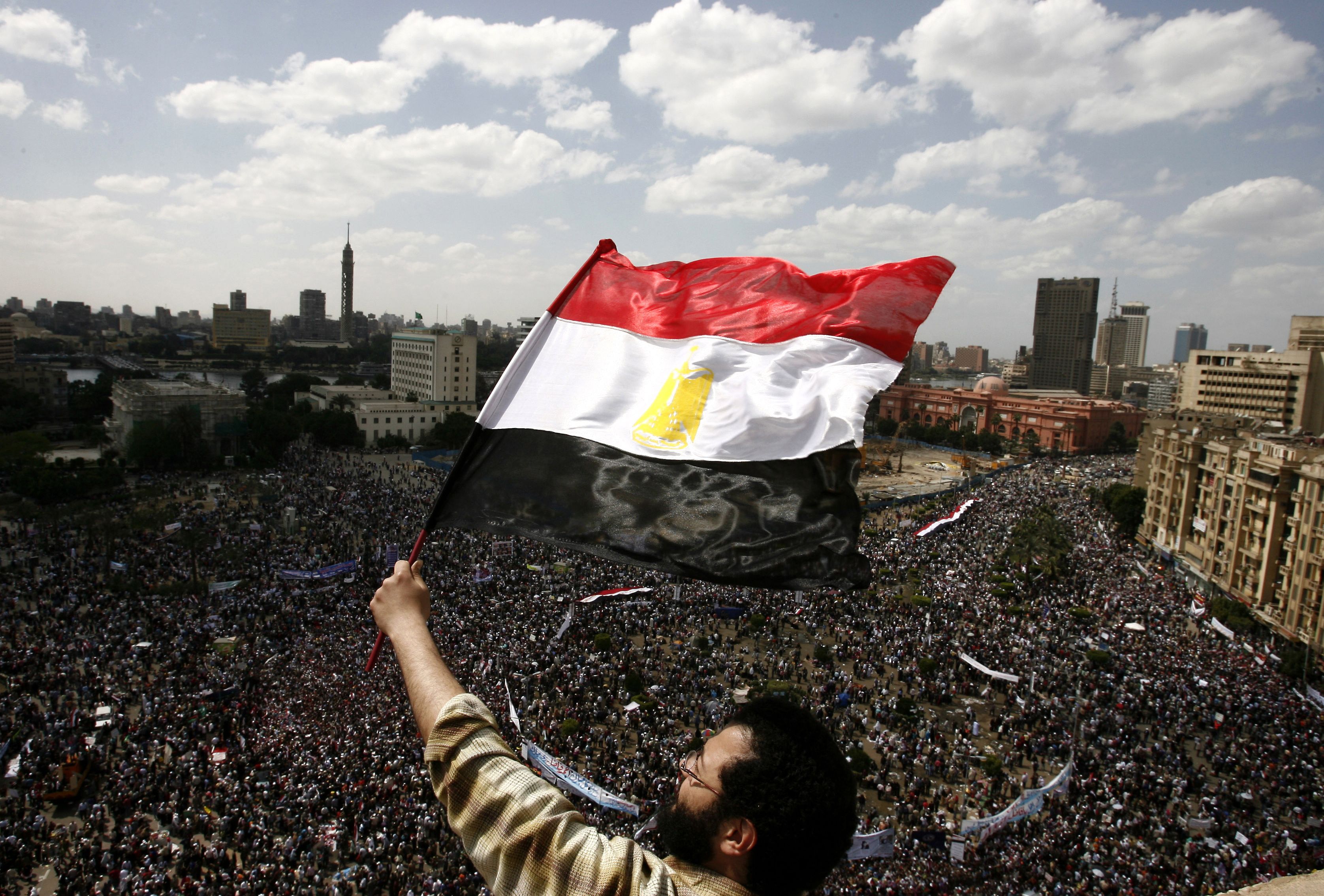

Military Dictatorship. It's quite another Cairo I come back to. New security measures have been introduced at the iconic Tahrir Square. Military police direct traffic. The roundabout has received a huge flagpole atop a plateau with an aesthetic that almost calls for military dictatorship. Open protests in the cityscape are unthinkable. Even the space of art and culture that flourished in the wake of the revolution is largely closed down. Now, surveillance cameras are hanging on every street corner – reportedly to prevent terror.

It is as if the young people who took part in the revolution suffered from a collective political depression.

The political room revolution opened, ended abruptly in the summer of 2013. The military coup that deposed Muslim Brotherhood President Muhammed Morsi was followed by a massacre of the Brotherhood's followers. The following year, Field Marshal Abdel Fattah el-Sisi took over the presidential chair. Since then, most civil and political freedoms have been under attack. In particular, members of the Muslim Brotherhood have been persecuted, but activists, journalists and trade unionists have also been arrested or have disappeared regularly.

It is as if the young people who took part in the revolution suffered from a collective political depression. Everyone knows someone in prison. Many have traveled from the country. But the worst is perhaps the loss of confidence. A friend describes how several old celebrities have become informants. He must be careful who he talks to. Before you know it, the police are at the door. The days when he could openly criticize the regime and talk about freedom and democracy are gone. Now he keeps revolutionary ideas to himself, trying to live his life from day to day as best he can while waiting for a new political spring.

On January 14, 2011, Tunisians packed the streets of their capital and overthrew longtime dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who shook the Middle East, setting off the hopeful uprisings that came to be known as the Arab Spring. / AFP / MISAM SALEH / TO GO WITH AFP STORY BY GUILLAUME KLEIN

Crises in line. Although the days of the revolution seem very far away in modern-day Egypt, none of the causes of the uprising have come to any solution. The slogan of bread, freedom and social justice is as unattainable as under Mubarak. Rather, the situation has gotten worse, and the gap between those who rule the country and the people has, if possible, deepened. With the introduction of Trump in the United States, we in the West have learned what the Egyptians have known for a long time: how the authoritarian often manifests itself in a total lack of contact with reality (Trump has described Sisi as "a fantastic guy"). Egypt already had structural economic problems before the revolution. The loss of income and foreign currency from the tourism industry in the aftermath has led to further pressure on the economy. While most people struggle to make ends meet, the authorities have launched mega-projects that are most suitable for snorkeling, where politicians and generals radiate an unshakable belief that MubarakEgypt is on the rise.

“When we watch TV, we find that Egypt is like Vienna. When we are in the streets, we find that Egypt is like Somalia's cousin! ” A video of a tuk-tuk driver went viral this fall when he uttered the words "everyone" feels, but dare not say. The driver exclaimed his frustration at the many crises people face, and his curse at the elite living in rushes and then without thought of the country's poor constitution. There is a shortage of basic products such as rice, sugar and oil. Since the Egyptian pound moved to a floating exchange rate last fall, prices of imported goods have skyrocketed. The pharmaceutical companies stopped producing some medicines because the raw materials became too expensive. The tightening of old subsidies on basic commodities has made life difficult for many. The regime's solution has so far been to let the military buy up large quantities of basic goods and sell them cheaply in their own stores. With that, the military's grip on the Egyptian economy, and the status of its own state in the state, has strengthened.

The slogan of bread, freedom and social justice is as unattainable as under Mubarak.

How long can it last? The video of the tuk-tuk driver was quickly removed from the TV channel's website. It doesn't fit with content that goes against the official narrative: "Egypt is on the road to recovery. Under President Sisi's steadfast leadership, the country will regain its lost greatness. ” In one of the English-language newspapers, I can read a comprehensive look at the country's economy after the transition to a floating exchange rate. The top executives at the big banks have been interviewed, and they can all as one report that although there is a slight decline, the pound will strengthen in the third or fourth quarter, and then there will be economic growth and prosperity throughout.

How many people believe them is an open question – but there is no doubt that the appetite for rebellion has subsided in light of the development of the Middle East in recent years. For every crisis, one can at least say to themselves: "We are not where Syria, Libya and Yemen are." But how long can it last? Continuing Egypt in the downward spiral the country is now in, it will probably only be a matter of time before the need for change again overshadows the fear of the consequences.