(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

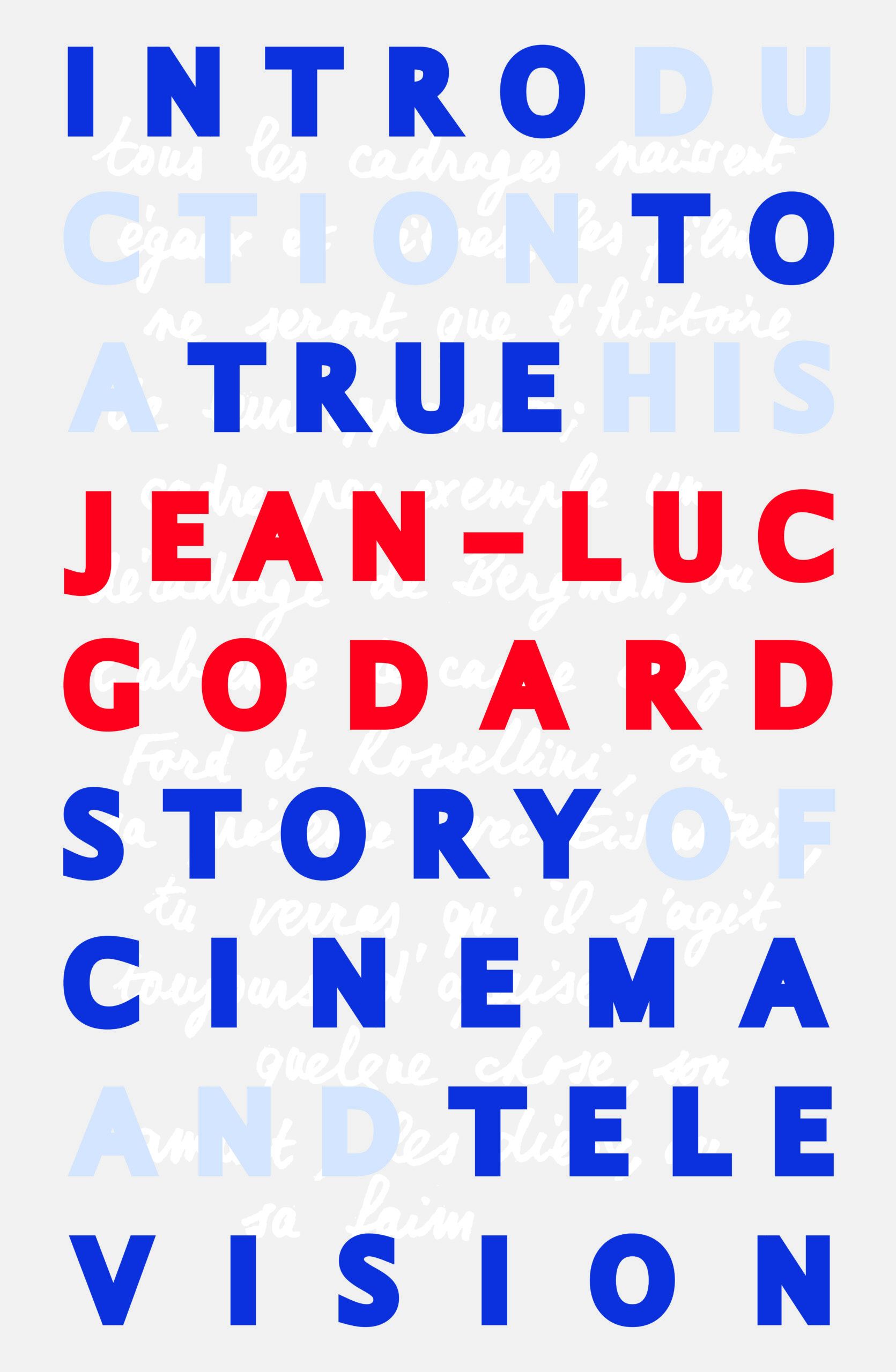

Jean-Luc Godard:

Introduction to a True History of Cinema and Television

Caboose, 2014

"Living in Europe means living in a Cartesian system that tells you not to contradict yourself." However, French-Swiss filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, who utters these words, has never been afraid to come up with contradictions ; rather, he has embraced them as a critical method.

The contradiction holds two perspectives – which for Godard is better than one. Here he is inspired, among other things, by the dialectical thinking of Karl Marx and the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein; In his own thinking and filmmaking, Godard has followed a cinematic montage principle for decades: to create connections between fragments (ideas, perspectives, texts, notes, pictures, sounds) that initially express opposite views, or which at least do not have an original context.

I Introduction to a True History of Cinema and Television, the first English-language transcription of a lecture series he held in Montreal in 1978, one gets to meet Godard in a familiar, erratic style, reflecting on his own films and their relationship to film history, film industry and the unrealized potential of art form (whose sprouts lay in the silent film) .

The publication is important not only because it makes this rich material available to new readers, but because it corrects some problematic aspects of French transcription, published in book form in 1980 – including the exclusion of dialogue with Godard's "sparring partner" during lectures, the Yugoslavian the film writer Serge Losique.

Uncategorizable. "They categorized me as uncategorable," Godard says somewhere in the book. The filmmaker is not just a characteristic, but a concept and icon in the modernist post-war film. As Losique writes in the book's preface, Godard "redefined" how to watch film.

Godard has always seemed to be moving, changing opinions, shifting viewpoints, chirping, letting a sudden association break a continuous line of thought – and leaving this to his films, which often have a fragmentary quality. IN Introduction ... he says that this is one of the reasons why he prefers to work in a certain sense of television, "where the concept of the fragment is allowed".

From the debut film Breathless (To Last Breath, 1959) to its preliminary last, Adieu au langage (2014), Godard has repeatedly reviewed what film is and where he himself is in the film's history. In the latter part of his career, he has also explored how film has played an important role in a larger historical perspective, and how television, video and new media have created new, limited opportunities.

challenges and challenges in how we communicate with images.

Introduction ... is a book with many – and sometimes contradictory – ideas. Some of them confirm and elaborate on things Godard has stated on previous occasions or expressed in his films, but many of them also break with some notions one may have of the director. Did you know, for example, that Godard would actually film Breathless – a film known for its rugged street photography and quick spontaneity – in a studio, and not in the streets of Paris?

For those who are already interested in Godard and / or the film's relationship to history, this book is a gold mine that it is difficult to recommend highly enough. But Introduction… is also a book that can both delight and communicate with – and not least entertain – readers who are basically neither interested in film history, film theory or Godard. The language is relatively free of subject terminology, and Godard often uses food and sports metaphors to explain his thoughts on film.

History (s) of cinema. The material collected in this book can be seen as an important part of a major film historical project Godard has been working on since the late 1960s. As Godard biography author Michael Witt points out in an introductory text, the Montreal lectures were part of a multimedia and experimental study of the film's history that resulted in books, CDs, exhibitions and DVDs, including the immense work History (s) of cinema (1998-2001).

This project is about a new way of "making" film history – using a new method, a new approach that relies more on (audio) visual thinking than the well-established, contextual and writing-based story writing.

According to Witt, Godard was mainly inspired by two figures in this work: the film conservator Henri Langlois and the art theorist André Malraux. From the former, who died in advance of the project, Godard continued a particular attitude, curiosity and method – to show and discuss films and film excerpts that initially, apparently, had nothing to do with each other.

The idea was to create new relationships between films to discover new truths about films as expressions; to think of film history in a way that was true to the film language's specific, audiovisual way of thinking. In line with this, the lectures were held right after the film screenings; every lecture day, one Godard movie was shown, just after showing excerpts from other films that Godard thought had some kind of link to his own film. It is essential to see the text in the context of these views, and this context is clearly stated in the book.

Michael Witt points out that Godard's project here is related to Malraux's art historical studies, which included comparisons between "contrasting treatments of the same motif" and which pointed to "stylistic similarities between works produced in very different contexts". Witt also shows Maulraux's influence on Godard's more comprehensive perspective: "Godard inherited from Malraux an inclusive, global vision of art, and an associative, non-chronological, visual, poetic and philosophical approach to storytelling."

Movies have become synonymous with stars, millions, mass merchandise and professional script; but what could it have been?

More specifically, Godard adopted Malraux's "concept of the artist as reality rival, rather than its transcript, "and his" concept of the function of art as the transfiguration and compensation of reality, rather than its mere imitation or representation. " This point is very important and can help one understand Godard's problematization of the hegemonic conveyance of the film's history. In particular, the first twelve pages of Witt's text provide an excellent introduction to the project's ideological and methodological background.

The film's unrealized potential. Something that has always been important to Godard, and which is often themed in Introduction…, Is the question of what movie could been. Godard questions the circumstances we take for granted, arguing against the dominant ways of thinking about film. Throughout the book, there is also a liberating demystification of filmmaking, as well as a generalization of "the great artist".

Movies have become synonymous with stars, millions, mass merchandise and professional script; but what could it have been? Yes, a handy language that many could use to express themselves and communicate (with their neighbors, friends, friends), and to see themselves in the world.

Godard discusses the consequences of film production being so expensive, and why one should always try to reach as many audiences as possible ("a totalitarian idea"). He also agrees with the idea that you have to have a script to make a film (he himself has based his films on notes). He asks why the film frame is square, and the camera lens round; why a film should last one and a half to two hours – "a complete idiotic length" – and what we lost when the sound and verbal language really took over the film.

"What I believe in is the potential for change," says Godard; for him, the film's pictures represent just that. The way he sees it, the silent film introduced a new relationship to the world, a new means of seeing, communicating and orienting us in the world with which the speech film failed to continue. "I think the movie's story is like a kid who could have learned something a little differently, or who started to understand something else," he says. The speech film "normalized" the film by incorporating it into the verbal language's cage: "Pictures are freedom, and words are prison."

He asks why the movie frame is square and the camera lens round; why a movie should last for one and a half to two hours – "a complete idiotic length".

The film's pictures have a different power, behavior and truth value than the words: "Pictures are not orders. You place them in a certain order to allow a certain way of living to come out of them. " Unfortunately, children learn to read before learning to see, he believes. In a provocative statement that echoes Michel Foucault, Godard suggests that the reason why ever-younger children need to learn to read is to prevent them from seeing how they can overturn the world as it is arranged.

Practical utility. Many people probably associate Godard with high-flying leaps of thought, abstract ideas and a very theoretical approach to film. His films can be intimidating and unapproachable to an ordinary audience – people who simply and entertained want to entertain and watch a good movie. Many would argue that they are primarily of interest to the theoretical film enthusiasts.

But when a reader Introduction … There is something else that strikes one: Here Godard is consistently concerned with practical issues and films practical utility, such an X-ray is useful for the physician and the patient.

A key replica in Introduction ... comes where Godard writes about how to look when watching film and television: "You don't see yourself in the world, you see yourself on the inside of yourself." However, the film's unfulfilled promise was that it would throw us into the world, to the outside of ourselves. The book shows us a film history thinking that leaves this quality as a central focal point.

In an oral, often fun, entertaining and trying way – the verbal form gives us several thoughtless thoughts and half-worded phrases – coming Introduction … With a demanding challenge: to think of film history with an eye for the unfulfilled possibilities of film media. And embrace the fragments and audiovisual thoughts we encounter that contradict the usual discourse.