(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

On a May day just over a year after the end of World War II, the Swedish Governor Ivar Rooth was a guest of his colleagues in Switzerland. Both countries were under strong pressure from the so-called Tripartite Commission, led by the United States with England and France as assistants.

The victorious powers demanded the repayment of all the stolen gold that neutral countries had received from Berlin during the war. The Swiss had initially rejected the claim. All gold transactions with the Third Reich had taken place on normal business terms, they believed. No basis was recognized for a claim for repayment.

The first hearing in March 1946 had ended in collapse. The country's chief negotiator, Walter Stucki, left Washington in protest. Now they were in round number two. The Swiss had been confronted with evidence that they had received large quantities of gold stolen from Belgium by the Germans.

Their new tactic was to offer goodwill payment without admitting they knew the gold was stolen. The commission's demand was originally for 200 million dollars. On the basis of available documents, it was calculated that Switzerland had received a sum equivalent to 25 billion Swedish kroner (equivalent to 40 million Norwegian kroner today) in stolen gold. The Swiss offered 4,5 billion in compensation without acknowledging any debt.

The stolen gold had passed on to the neutral and allied states during World War II: Sweden, Portugal, Spain and Turkey

Gold as a means of payment

A third of the stolen gold had passed on to the neutral and allied states during the Second World War: Sweden, Portugal, Spain and Turkey. It was clear to everyone how the transactions had taken place: Germany had no way to pay for the import of war material and strategically important goods with valid currency. Via the national bank in the Swiss capital of Bern, gold could be continuously exchanged for Swiss francs, or the gold transferred directly to the country to which one owed money.

It was the National Bank's deputy head Roissy who came up with the idea for the international gold depository. In the autumn of 1942 he had visited Spain and Portugal to discuss common problems. When he returned home, he wrote a three-page report in which he noted that Portugal could no longer accept gold as currency from Berlin, "partly for political reasons, partly as a legal precaution". But, he noted, there was a solution: “Your objections fall away if the gold does not come directly from Berlin, but passes through our hands. We should think about it.”

In the spring of 1946, Roissy's protocol was a secret to all but the innermost circle of the Swiss power elite. And the Swedish Riksbank governor, who during the war was a regular guest in Bern and Basel, was aware that the Swiss' role as intermediaries until 1944 had been the prerequisite for Sweden's wartime settlement with Germany. In May 1944, the Swiss National Bank described the case in sober terms: "These conditions are unknown to the public. That is why Sweden is also not named in newspaper articles as a buyer of 'stolen gold'. In general, Switzerland acts as a curtain. It gives us an alibi.”

But in the minutes of the National Bank's Executive Board from May 1946, the Swedish Riksbank Governor Ivar Rooth confirmed another truth. Germany's deputy governor Emil Puhl had – Rooth explained on 18 February 1943 to "a Swedish trade delegation" – assured that no stolen gold had been transferred to Sweden's Riksbank. All gold received during the war had been "old", and no gold had been accepted after 15 January 1944. A central Swedish figure thus supported, in a sensitive negotiating position, the Swiss rejection. But towards the end of the protocol there is a passage which, with today's knowledge, has a particularly explosive power:

Jewels, watches, spectacle frames, dental gold and other gold objects in great abundance, taken from Jews, victims of the concentration camps.

"Finally, Rooth declared that he had been firmly convinced that Puhl had only told the truth, and that he had not prescribed his soul to the National Socialist Party. He had agreed to transfer the gold in this way from the conversations between Puhl and Hechler which he had overheard during his time in Basel, information which would no doubt have cost both gentlemen their lives if they had come to the regime's ear."

Germany's Deputy Governor Emil Puhl

Who was this Emil Puhl? Let me quote a legal document dated twenty days before the Swiss verdict on Rooth's position on the gold question: Baden-Baden, Germany, May 3, 1946. Emil Puhl, duly sworn, declares:

"My name is Emil Puhl. I was born on August 28, 1889 in Berlin. I was appointed a member of the Riksbank's board in 1935 and deputy governor of the Riksbank in 1939. I served without interruption in these functions until Germany's capitulation. In the summer of 1942, Walter Funk, head of the Riksbank and Minister of Economy in the German Reich, had a conversation with me and Mr. Friedrich Wilhelm, a board member of the bank. Funk told me that he had agreed with Himmler that the Riksbank should receive gold and jewels for safekeeping on behalf of the SS. Funk ordered to make an agreement about the forms with Pohl, who as head of the SS was to receive gold and jewels for safekeeping. The material deposited by the SS included jewels, watches, eyeglass frames, dental gold and other gold objects in great abundance, obtained from Jews, concentration camp victims and other persons in the SS. [...] At regular intervals, as part of my duties, I visited the Riksbank's archive and paid for what was in stock. Gold Discount Bank, under Funk's leadership, also established a current account that eventually reached 10-12 million reiksmark to be used by the SS's business department to finance material production in concentration camp factories run by the SS.

I understand the English language and assure you that these statements are in line with everything I know and believe.”

The testimony is included in the minutes from the Nuremberg trial. It became central to the life sentence against Economy Minister Walter Funk. And it was through him that the world received the first confirmation from one of those responsible that the looting right up to the gold of the victims of the holocaust was run as a carefully planned business project, and that holocaust gold was also included in Germany's agreements with neutral countries. Testimony from SS officers and Puhl's own subordinates eventually led to Puhl himself being put on trial.

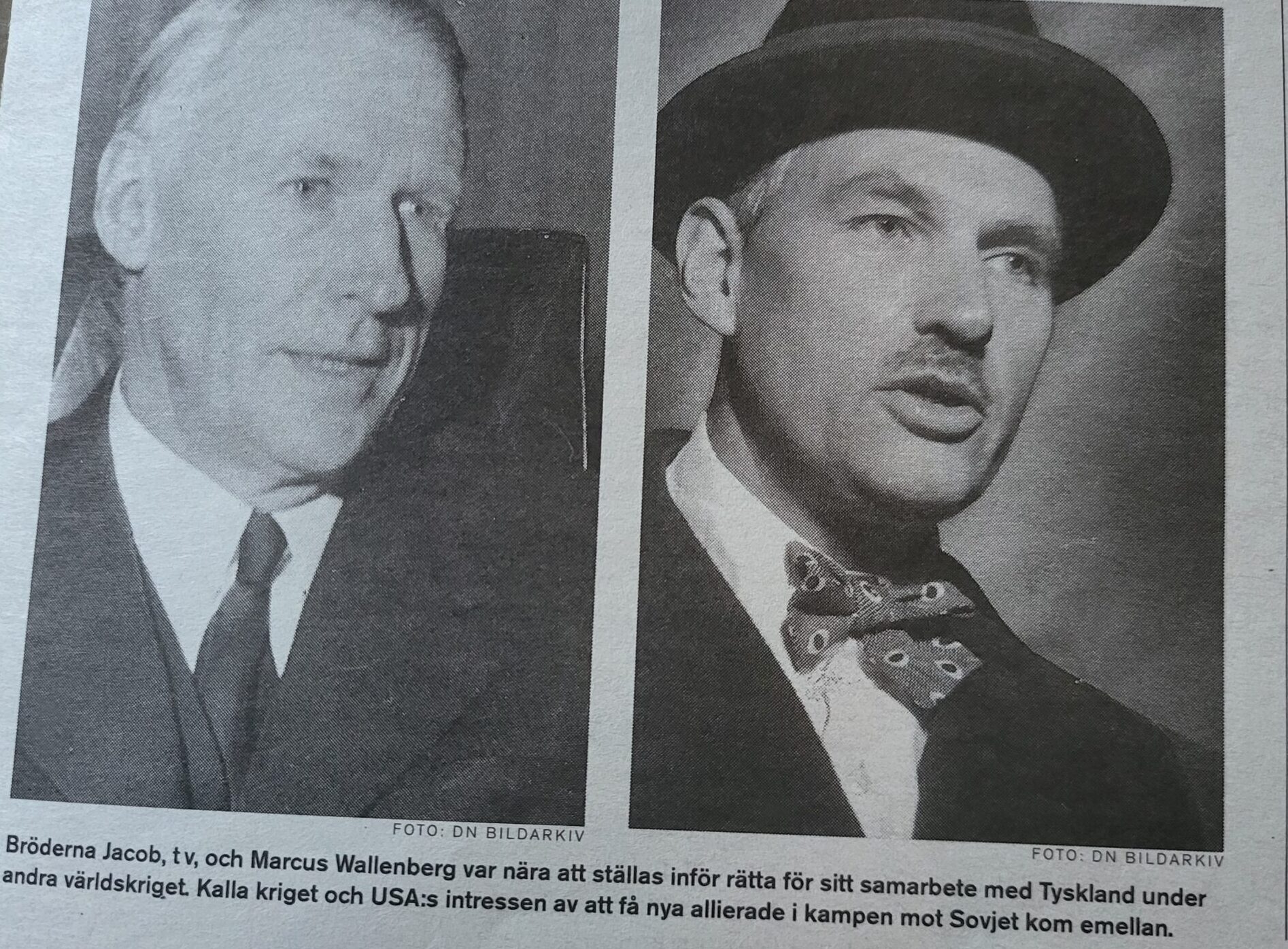

The Wallenberg Group

In the last war criminal trial, the so-called Wilhelmstrasse trial in 1949, Puhl was sentenced to five years in prison as the main person responsible for the holocaust's handling of valuables.

Earlier, in February 1943, the Swedish government had advised Ivar Rooth to ask Emil Puhl whether the German gold could be considered dirty. At the same time – as the researchers Göran Elgemyr and Sven Fredrik Hedin [a work for which they received the Golden Spade in 1998 for their digging journalism] have shown – they were told not to investigate the matter on their own, and it was to Puhl banker Jacob Wallenberg on behalf of the official Gunnar Hägglöf in the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs shortly afterwards asked about the dirty gold and, as expected, received a negative answer.

It was Puhl, in his capacity as General Manager of the German Reichsbank, who had approved the gold agreement in 1943-44. Then the Wallenberg group secretly received values worth 90 million Swedish kroner for its role as a bulwark for German Bosch. It was Puhl who in June 1944 was received on a visit of honor in Stockholm, with receptions and dinners both at government level and among the financial elite. And it was this chief administrator of the holocaust gold who appeared as an unofficial reference when, in the autumn of 1944, Jacob Wallenberg tried to get the Riksbank to approve yet another gold transaction.

Three weeks after Puhl testified, Ivar Rooth, apparently unaware of what his old friend had admitted to the Americans, testified that his friend had certainly not surrendered his soul to Nazism. After that, the German main actor behind Sweden's war agreements disappears into the darkness of history. The archives of Dagens Nyheter and Expressen do not contain the slightest hint that the trial against him was fundamental to the recognition that the holocaust was not only about mass murder, but also about money.

Master Manipulator Puhl

None of the Swedes involved could have known about Puhl's dark role during the war. But the war crimes trials were conducted in full public view. This is where the narrowing comes in. Swedish historians have never considered him the master manipulator of stolen gold in Sweden that he was during World War II. But the Swiss mentioned above could not suppress him as effectively.

Puhl persuaded the Swiss a month before the end of the war to again receive three tons of gold.

The Swiss government's defensive position vis-à-vis the Tripartite Commission was that in the spring and winter of 1945 it had agreed to US demands to stop its gold deals. In other words, it claimed in action to have taken a stand for the Allied side. But while this line was being pursued, Senator Harley M. Kilgore published in his committee in Washington four letters sent by Emil Puhl of Switzerland to Economy Minister Funk in March and April 1945. They report in detail how Puhl had persuaded the Swiss to a month before the end of the war again to receive three tons of gold. And among his Swiss contacts was the same Walter Stucki who after the war was to defend Switzerland before the commission.

As a conclusion to his last letter from Switzerland to Walter Funk, dated 6 April 1945, Puhl looks back on another successful negotiation, despite almost impossible external conditions. And the reason for the success? "The personal contacts have, as before, been characterized by the greatest friendliness, which is of decisive importance in all negotiations. In other words, these are worth cultivating.”

In his book Looted gold from Germany ("Rovgull fra Tymskland", 1997) the Swiss journalist Werner has revealed an economic and political pattern that was not only used in Switzerland and Sweden: Those in power chose to regard business relations with the Third Reich as "business as usual".