(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Susan Williams:

Spies in the Congo. The Race for the Ore that Built the Atomic Bomb

Hurst Publishers, 2016

Let's start from the back. With what never happened: On the seventieth anniversary of the Hiroshima tragedy in 2015, there was no mark in the small uranium mining town of Shinkolobwe in southern Congo, which was the site of the bomb. No one spoke for the thousands born in the miners' families, without arms, legs, normal heads, and with other serious bodily defects. No politician lamented the West's large-scale theft of the Congolese uranium. No one initiated health projects to remedy the horrific human damage that still appears regularly in the area. No, there was no mark to honor the Hiroshima bomb's first victims: the miners in Shinkolobwe.

Let's start from the back. With what never happened: On the seventieth anniversary of the Hiroshima tragedy in 2015, there was no mark in the small uranium mining town of Shinkolobwe in southern Congo, which was the site of the bomb. No one spoke for the thousands born in the miners' families, without arms, legs, normal heads, and with other serious bodily defects. No politician lamented the West's large-scale theft of the Congolese uranium. No one initiated health projects to remedy the horrific human damage that still appears regularly in the area. No, there was no mark to honor the Hiroshima bomb's first victims: the miners in Shinkolobwe.

The logic of war. Writer and historian Susan Williams grew up in the area, in Zambia just south of Katanga, Congo. She knows the sources. In recent years she has had access to archives and interviewed people who contribute with unique knowledge. British colonial tradition has hindered good archival and document access. Partly because things were never documented, partly because the material was destroyed and partly because the documents were moved to inaccessible "non-archive archives," closed forever. The British have a penchant for using the "national security stamp" also on things dating back hundreds of years. The British Empire was no more humane than others – just prettier wrapped and marketed. Transparency is not a typical British trademark, but it is a different story.

But Williams digs, compares and equates sources – and has ended up with a unique collection of material of both trivialities and heavier material that together gives life to this important story. Williams shows us the human cost, side by side with the monstrous and targeted waste of time that the colonies' resources were drained, where the price was paid by the poorest of the poor. She describes both everyday and special situations, and does not fail to give us rational explanations of what is happening: the fight against Nazism and fascism, and the logic of the world of war and intelligence and espionage. One by one, individuals are drawn in a significant gallery of characters who secretly hunt uranium in this important part of the world at this fateful time in history. "Rud" Boulton, codenamed Nyanza. "Dock" Hogue, codenamed Ebert, located in Mozambique, and later Accra in Ghana (then the Gold Coast). Project manager Donovan had been given extensive financial powers.

But Williams digs, compares and equates sources – and has ended up with a unique collection of material of both trivialities and heavier material that together gives life to this important story. Williams shows us the human cost, side by side with the monstrous and targeted waste of time that the colonies' resources were drained, where the price was paid by the poorest of the poor. She describes both everyday and special situations, and does not fail to give us rational explanations of what is happening: the fight against Nazism and fascism, and the logic of the world of war and intelligence and espionage. One by one, individuals are drawn in a significant gallery of characters who secretly hunt uranium in this important part of the world at this fateful time in history. "Rud" Boulton, codenamed Nyanza. "Dock" Hogue, codenamed Ebert, located in Mozambique, and later Accra in Ghana (then the Gold Coast). Project manager Donovan had been given extensive financial powers.

Williams takes us on one tour de force in imperialist arrogance and serial abuse.

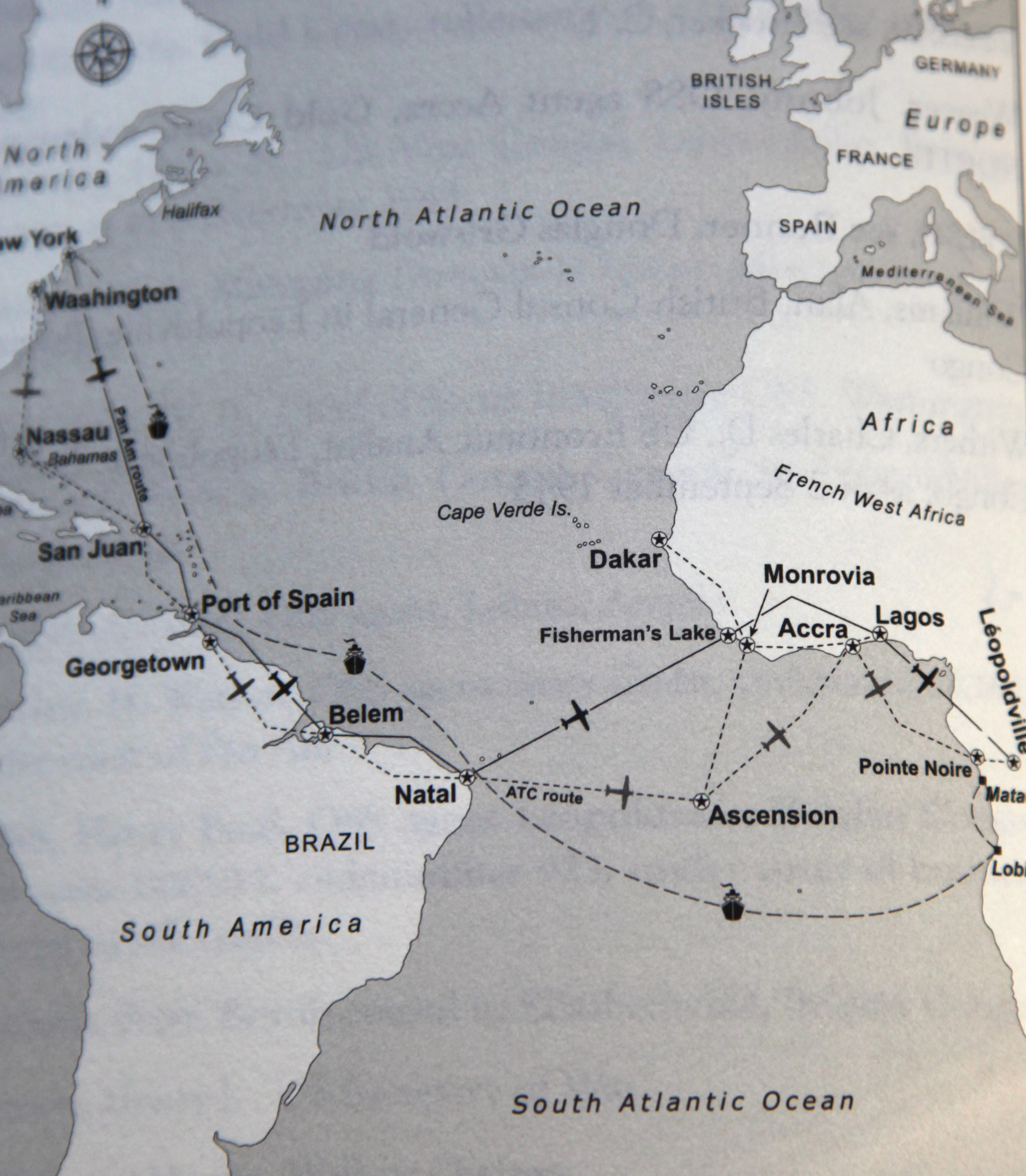

Race. The Americans and the British come together, huge sums are allocated and a breathtaking race that draws lines across half the globe begins. The hunt for uranium must take place in secret, the shipment must take place in secret – and one must prevent Germany from becoming suspicious. The vulnerable route zigzags via Angola back to Congo and Ghana, then over to Brazil, from there via Trinidad to New York and on to scientists in Tennessee. The agents travel under the guise of being tourists, game photographers, gold hunters, diamond smugglers and oil agents. Agent Armand Denis is a "hidden" smuggler of gorillas. It is joked that the best way to smuggle uranium is to hide it under a load of drugs. They must know the languages and master the cultural codes both locally, in business and in diplomacy. Workers must be provided for the mines and shipping routes created that do not attract attention. No one should know about the real purpose, which is the Manhattan project and the atomic bomb. And most of those involved have knowledge of just one or a few links in the long chain that leads from Shinkolobwe to the American desert city where the hell bomb is to be produced. The opposing forces are not just "unreliable African culture and labor", demanding weather gods and logistics under tropical conditions, but infiltrating Nazi forces and interests and other great power competition. The novel is about this network of spies and soldiers, and takes us from the world war into the cold war.

Race. The Americans and the British come together, huge sums are allocated and a breathtaking race that draws lines across half the globe begins. The hunt for uranium must take place in secret, the shipment must take place in secret – and one must prevent Germany from becoming suspicious. The vulnerable route zigzags via Angola back to Congo and Ghana, then over to Brazil, from there via Trinidad to New York and on to scientists in Tennessee. The agents travel under the guise of being tourists, game photographers, gold hunters, diamond smugglers and oil agents. Agent Armand Denis is a "hidden" smuggler of gorillas. It is joked that the best way to smuggle uranium is to hide it under a load of drugs. They must know the languages and master the cultural codes both locally, in business and in diplomacy. Workers must be provided for the mines and shipping routes created that do not attract attention. No one should know about the real purpose, which is the Manhattan project and the atomic bomb. And most of those involved have knowledge of just one or a few links in the long chain that leads from Shinkolobwe to the American desert city where the hell bomb is to be produced. The opposing forces are not just "unreliable African culture and labor", demanding weather gods and logistics under tropical conditions, but infiltrating Nazi forces and interests and other great power competition. The novel is about this network of spies and soldiers, and takes us from the world war into the cold war.

Abuses. Williams takes us on one tour de force in imperialist arrogance and serial abuse. It is the West's needs and interests that are at stake and mean something – everything else is subject to this. Local forces are called in for underpaid forced labor. In the tradition of Belgian King Léopold, corporal punishment, imprisonment and death threats drive the workers into the mines – without protection and with minimal mechanical assistance. The image of Africa is broad and diverse and linked to events in Europe: The synagogue in Elisabethville is attacked when Belgium introduces the Jewish Star Order in 1942.

The mines are of course owned by Belgians, and it is to Belgium that the enormous profits go. But even the management of Union Minière seems without knowledge of the "burning stones" they extract from the mines. At his headquarters in Shinkalobwe, Williams quotes the American author John Günther, who describes that large stones of "brilliant, hideous ore" lay in front. "Do you not know that you will become sterile from this?" he laughs, but is rejected by the engineers who say they already have enough children. At the next visit, however, the stones are gone. The whites also soon stop drinking water from the area.

It is joked that the best way to smuggle uranium is to hide it under a load of drugs.

Heavy shadow. There is a strong tone of anti-racism in Williams' approach to the drug. She reveals the contempt for African considerations and interests, and the burdens that southern Congo has had to bear as a consequence of colonialism. In comparison, she mentions that around the waste site after the Congo uranium in the USA, there is a health project of five million kroner annually to remedy needs. To date, the Congo has not even mapped out the consequences of uranium mining. But people feel it on their bodies: babies without normally developed heads, hands and legs, and cancer in all its forms. New generations who also notice the consequences, when thousands of poor people still go down into the unsecured mines in search of a few kroner in valuable minerals.

The first victims of the Hiroshima bomb in Shinkolobwe are bypassed when the first atomic bomb is commemorated. But the shadows from the big mushroom cloud may rest heavier over Katanga than anywhere else today. As the playwright Harold Pinter bitterly pointed out in his far too little read (and for BBC-transmitted) Nobel speech in 2005: «But you would not know it. It never happened, nothing ever happened. Even while it was happening it was not happening. It did not matter. It was of no interest. "

Susan Williams has made a documentary in the spirit of Pinter. "This must be of interest, ”they say. Once again, she has unearthed aspects of our recent history that we can no longer let go.