(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

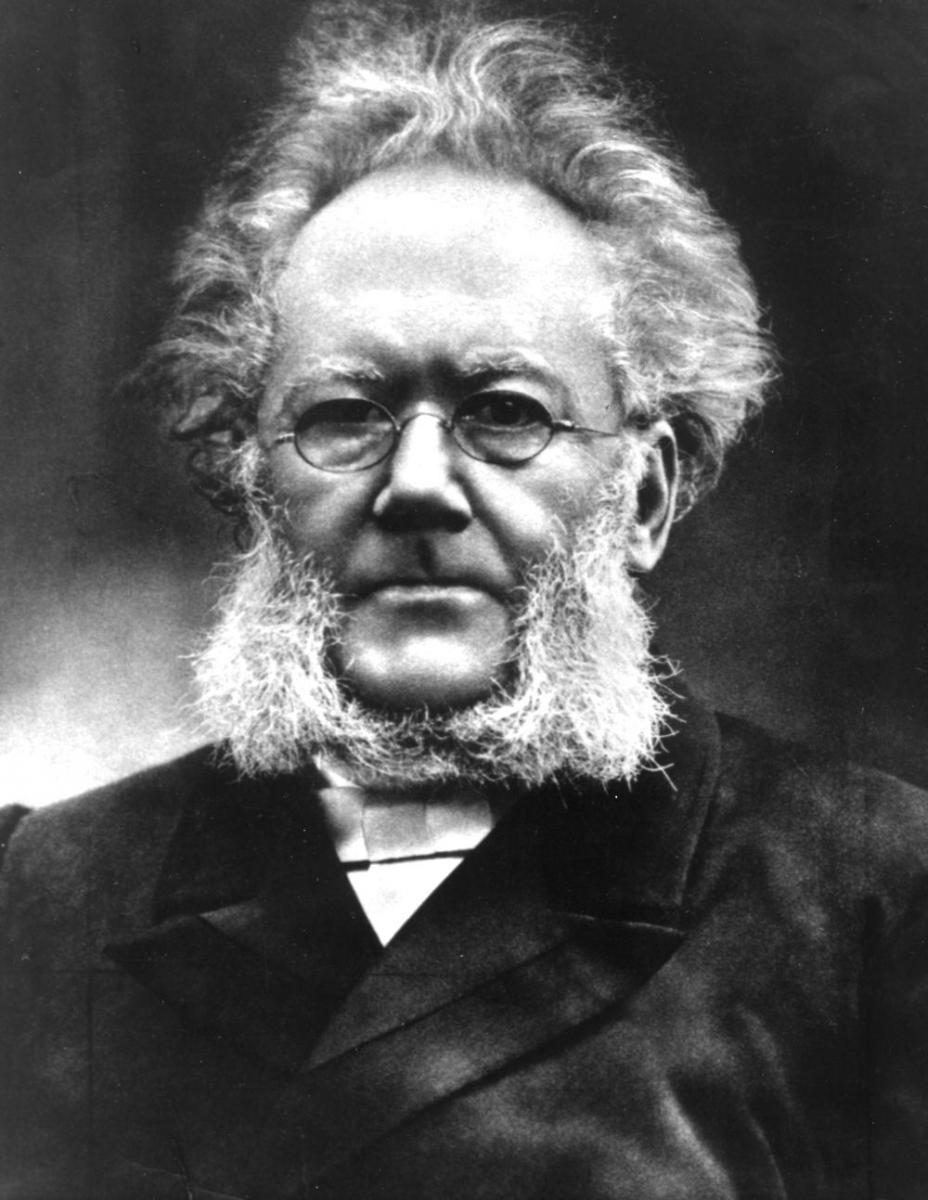

The Nordic region's leading literary critic Georg Branded visited Norway in May 1890 and gave a lecture on «Henrik Ibsen and his school in Germany". Among other things, he reviewed an Ibsen-inspired drama in which a man appeared after escaping from the "Insane Asylum, still wearing a straitjacket". On that occasion, the medicine professor Ferdinand Lochmann came out against Brandes and Ibsen in Morgenbladet. The drama made Lochmann think of a mental hospital:

"Dr. Henrik Ibsen has [...] made a number of young German writers disturbed in the head, they are perfectly mature for the insane asylums, they only need to bring their dramas to legitimize themselves for admission, and the director will put them in a cell as soon as possible."

Then Ibsen's drama Hedda Gabler came out in December 1890, a Danish reviewer characterized the main character as "a Tiger Nature, dressed in a Lady's Similitude, but with the old wild Blood under her pale Skin and not always able to tame it". Dagbladets critic tried to explain Hedda through the concept of "atavism", the fact that an earlier stage of development suddenly breaks through.

"We doubted Strindberg's Women and we do so even more so in Ibsen's Hedda. However, who disputes Atavism? Who dares to deny that in a single individual, even in the middle of cultural life, it can penetrate the primordial operational and emotional life from that time, when living life was everyone's war against everyone." Georg Brandes claimed that Hedda Gabler was a "true Degeneration type", while another reviewer spoke of Ibsen having written an "abnormal" drama.

The terms "degeneration" and "atavism" enjoyed popularity in evolutionary theory and Darwinism. They were used to explain criminal acts and so-called moral idiocy, that the individual was so primitively developed that there was no difference between right and wrong. These were common associations with what was understood as "abnormality" and "decadence". A French critic wrote about Hedda Gabler:

"Hedda is basically nothing more than a tragic bluestocking, an affected lady who is not ridiculous, but criminal. She steals, kills or facilitates murder and kills herself, all in honor of I don't know what demented ideal, dreamed up by a crazed imagination. How they will love this type of woman, all our literary scumbags, our female salon beauticians, our beautiful decadents!”

Women and "primitive races"

Decadence became an argument that women should not receive higher education. In 1891, the journal Samtiden printed an article by the French physician and anthropologist Gustave Le Bon in which it was said:

"I do not know whether two generations of ungraduated women would raise the intellectual level of France, but what I do know is that they would bring about a terrible decadence in the nation, and that an inordinate mortality would befall the rickety offspring of these bloodless, learned ladies. »

At the time, it was believed that rickets, which causes clubfoot and soft bones, was due to hereditary degeneration. We now know that vitamin D deficiency is the cause, and that the "degeneration" can be remedied with cod liver oil and more sunlight. The "argument" relied on period jargon. Another prejudice was the racial hierarchy, where the white European stood at the top of the pyramid. Gabriel Gram in Arne Garborg's decadent novel Tired Men (1891) expressed a widespread notion when he believed that the modern European, "with the help of his highly superior Intelligence", is "pushing back all his ancestors and spreading himself over the whole Earth. He will then gradually, through continued development, continued crossing between related races, as well as under the influence of increasingly favorable external circumstances, produce a type that stands just as high above us as we now stand above the branches of the bush".

At the time, it was believed that rickets, which causes clubfoot and soft bones, was due to hereditary degeneration. We now know that vitamin D deficiency is the cause, and that the "degeneration" can be remedied with cod liver oil and more sunlight. The "argument" relied on period jargon. Another prejudice was the racial hierarchy, where the white European stood at the top of the pyramid. Gabriel Gram in Arne Garborg's decadent novel Tired Men (1891) expressed a widespread notion when he believed that the modern European, "with the help of his highly superior Intelligence", is "pushing back all his ancestors and spreading himself over the whole Earth. He will then gradually, through continued development, continued crossing between related races, as well as under the influence of increasingly favorable external circumstances, produce a type that stands just as high above us as we now stand above the branches of the bush".

The woman's intelligence was compared to what was then perceived as primitive peoples. Morgenbladet was enthusiastic about Le Bon's article and echoed his views on "Woman's Spiritual Capabilities". In order to assess these, it was "almost necessary to draw a parallel between them primitive Racer's intellectual Standpoint and the Woman; one will find there the same incapacity to reason, the same inability to make connections and to separate the essential from the unimportant and the same habit of generalizing individual cases and drawing inaccurate conclusions from them".

"Morally Abnormal Fantasy Children"

In 1894, the literary historian started Christian Collin a great debate about decadence literature in Verdens Gang. The starting point was the staging of Gunnar Heiberg's play The balcony in Copenhagen. The female protagonist with Dagmar Orlamundt in the role of Julie made success. Collin immediately associated the erotically obsessed Julie with Ibsen's dramas:

"From primitive Racer's intellectual Standpoint and the Woman; there you will find the same inability to reason, the same inability to make connections and to separate the Essential from the Inconsequential." THE MORNING PAPER

"If at any time we were to be short of great geniuses, literary Norway could well at least become Europe's interesting Dwarf, who pleased or at least astonished by its natural difficulty and its artificial grimaces. Some of our poets' morally abnormal imaginations remind us of these small grotesque porcelain figures, which the French in particular liked to set up as trinkets, and which they call nest eggs. I believe that even Ibsen's Hedda Gabler and Hilde make a similar impression on many of Europe's connoisseurs of art. But Heiberg's Julie is certainly not left behind."

The "abnormal" had been a recurring feature in the characterization of Ibsen's female characters. Collin operated here on an associative level: Both dramatic figures could be compared to "magots". "Magot" in French can mean, among other things, a tailless monkey from Gibraltar or a grotesque, small porcelain sculpture from China or Japan. The combination of these two meanings pointed towards the notion of atavism, a word Collin did not use. The metaphor connected the abnormal with both the oriental and the primitive. Collin also departed without difficulty from the dramatic figures of the poet. The decadent poet had an imagination that "thrives best in the production of moral dissolution processes". He "enjoys the Abomination of Destruction."

The debate about literature in the 1880s and 90s was by no means just literary, but involved a number of disciplines: the word "abnormal" wove law, philosophy, criminology, psychiatry, biology and political ideology together in an obscure way. The jargon in these fields often governed the discussion of Ibsen's female characters. The German writer and physician Max Nordau, who wrote a two-volume work on degeneration (Entartung) in 1892-93, concluded that Ibsen's dramas were written for hysterical women, male masochists and the mentally retarded (Schwachköpfe).

In the period 1890–1896, "abnormal" women were associated with a number of different ideas: the immoral and criminal, hysteria and psychological pathology, acting out sexuality, atavism, it animal, the emotional, the degenerate, the "wild", "primitive" and oriental races, anarchistare and bohemians. It abnormale the woman often had a destructive influence on the man. All these associations were associated with the decadence as a spinal reflex. Such contemporary performances have been called a discourse.

Discourse analysis and civil society

The publicity surrounding Ibsen's female figures in the 1890s provides many examples of the actors manipulating, categorizing without discussion, reproducing prejudices and fighting for their own power more than for truth. The historian cannot therefore be blind to an abstract ideal of enlightenment à la Jürgen habermas and his classic Civil public (1962), where argumentation is paramount. Manipulative communication is thus seen as a decline that arose in the latter half of the 1800th century. In doing so, Habermas overlooked that such discourses have existed as long as we have had the public. The less explicit and irrelevant aspects of public opinion formation are often just as important as rational arguments.

This does not imply that a discourse analysis à la Michel Foucault is an alternative to the ideal of enlightened conversation, but it is useful for surveying the jargon typical of the period. What is missing is a focus on the public debate. In Michel Foucault's lectures on the abnormal (read anormaux) at the Collège de France from 1974-75, public word change does not play a role.

The attempt to label Ibsen's female characters as abnormal was publicly countered: the truth and evidentiary force of the "discourse" was challenged. Public debate in the 1890s did not simply consist of reproducing one or more discourses. When the debaters go on autopilot and only repeat collective and individual prejudices, one can of course easily get this impression.

#Hamsun#'s program-essay "Fra det unobjeste Sjæleliv" showed the way for development in the 1890s. He polemicized against Lochmann and told of a man who shot his neighbor's horse because "The horse's crooked gaze bored him madly through the nerves".

"How would a man like that get out in a Norwegian novel? Time for Gaustad! This strong, flaming healthy Man is ripe for Gaustad! I only know one Psychologist who could describe this Figure; not Dostoevsky, who makes even normal people abnormal, but Goncourt."

Hamsun balanced between abnormality, institutionalized madness and sanity on a very tight line. He who shot the horse because he felt the look went "crazily through the nerves", was not abnormal, according to Hamsun. The play shifted the "discourse" away from Gaustad and made psychology an interesting topic for fiction.

Beyond the 1890s, the understanding of Ibsen's "abnormal" female characters and the psychological literature gained ground, while the perspectives of Lochmann and Collin were marginalized.

Nevertheless, decadence did not survive as a concept in literary histories. The price for recognition was that it was renamed "new romanticism", "new idealism" or "symbolism".

Only a hundred years later was decadence rehabilitated in monographs by Per Thomas Andersen (1992) and Per Buvik (2001).

The article is based on a recently published book by Eivind Tjønneland, "Abnormal" women – Henrik Ibsen and decadence (Vidar publishing house).