Forlag: (Israel)

(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

The new leader of the Israeli Labor Party, Avi Gabbay, speaks a language you are not used to hearing on the country's left. He has got many party veterans on their toes by declaring that he sees no reason to escape a single settlement from the West Bank in connection with a peace settlement. He has also refused to cooperate with the Arab Common List if given the task of forming government after an election. Not without reason, many people refer to him as "the new Likud".

His apparent counterpart, the prime minister and Likud chairman Benyamin Netanyahu, also speaks a language other than what was heard from previous generations of politicians from his part of the spectrum. Away is the talk of territories and Storisrael, and instead he constantly reminds of the so-called Iranian threat and talks about security, security and again security.

Socialism and revisionism. This contradiction, where it becomes increasingly difficult and difficult to see the difference between the two, is as drawn from the conclusion of a book that has been a focal point in the Israeli debate in recent months. The book is only now being translated into English where it will be called Catch 67. The author is religion and idea historian Micha Goodman, who here gives a signal of the ideological meltdown the Israelis have exposed themselves through the 50 years that have passed since the war in 1967. Or maybe the book should rather be seen as a kind of diagnosis.

Historian Shabtai Tevet describes the victory in 1967 as "the damned blessing".

However, Goodman's analysis dates back to the early 20th century. The emancipation of the Jews in the century before had failed, and the only way to fight anti-Semitism was to take the initiative and make the Jews a nation like everyone else. The way out of the exile involved separating themselves politically from Europe, standing out and establishing a state of its own.

This thought gave rise to two competing ideologies. On the one hand stood the socialist Zionism which was expressed, among other things, by the kibbutz movement. The goal was to create a Jewish majority state that lived in peace with its neighbors. On the other hand stood the revisionist Zionism, which has continued today in the form of the ruling Likud party. It also had a Jewish state as its goal, but with maximalism and liberalism as the core elements. Where the socialists were satisfied with a smaller state, but clearly Jewish, the revisionists worked for a state with the largest possible area, and in liberalism there was a respect for the individual and full rights of all citizens, whether Jews or not.

This thought gave rise to two competing ideologies. On the one hand stood the socialist Zionism which was expressed, among other things, by the kibbutz movement. The goal was to create a Jewish majority state that lived in peace with its neighbors. On the other hand stood the revisionist Zionism, which has continued today in the form of the ruling Likud party. It also had a Jewish state as its goal, but with maximalism and liberalism as the core elements. Where the socialists were satisfied with a smaller state, but clearly Jewish, the revisionists worked for a state with the largest possible area, and in liberalism there was a respect for the individual and full rights of all citizens, whether Jews or not.

Neither thing turned into something, and that's Goodman's point. The revisionists believed that they could create a Greater Israel and maintain a Jewish majority by massive Jewish immigration, and both this and socialist Zionism are today dead ideologies. The main explanation is the 1967 war, which stands as the dramatic turning point.

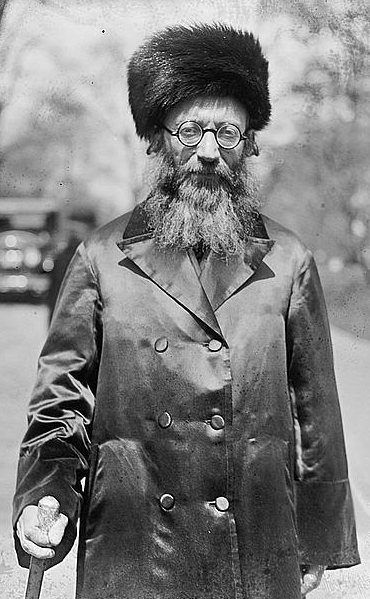

In a foreign body. At that time, Israel became an occupying power. It brought a third dream to the field, and it was about redemption: a divine redemption previously formulated by Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Kook. Unlike the secular Zionists, he believed not only that the land belonged to the Jewish people, but that the land was an integral part of the Jewish people. In his thinking every people has a soul which is its culture and a body which is its land. So for him, normality was not a matter of joining the nations family, but of getting the soul back into the body. And it had to be the right body.

As early as May 1948, it was the rabbi's son, Zvi Yehuda Kook, who continued his father's theology, and it was in 1967 that he became the spiritual lighthouse of the settler movement. The young Kook cried when the state was proclaimed – for in his eyes the Jewish soul had not dwelt in his own body, but in the body right next door. At biblical times, the Jews had not lived on the coastal plain where Tel Aviv is located and where 75 percent of the Israeli population lives today. There the Philistines and other peoples lived at that time, while the Jews lived up in the mountains, on the West Bank. In Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus.

Intifada alarm clock. This thinking has, in the time since 1967, knocked off the two secular ideologies, and here we meet the Israeli catch. The doctrine of the two became the two Palestinian intifadas manufactured by Goodman as the ultimate response to the war. During the first intifada, the revisionists seriously noticed that there is actually another people living in the country with national aspirations, and that blew the air out of the dream of Greater Israel. The other, the Al Aqsa intifada, gave the left the realization that one cannot control another people forever. On that occasion, the vision of peace died.

Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Kook believed not only that Israel belonged to the Jewish people, but that the country was an integral part of this people.

Another Israeli historian, Shabtai Tevet, describes the victory in 1967 as "the damned blessing," and Goodman is right for him. Because as a result of these bullets, the religious wing's notions of the holiness of the land have settled well and thoroughly in the population, which is mainly due to the fact that the other two do not really have anything to offer anymore. The right wing's territorial ambitions are gone, so today's argument for holding on to the occupied territories is security. The Left continues to whine about two-state solution and evacuation of the occupied territories, but for lack of substance and credibility, the word "peace" is no longer mentioned. Instead, it is talking about human rights and coexistence – about that at all.

Yes please, both. This view of bleakness is of the highest potency, but Goodman has something to argue with. For he sees that the Israelis are no longer able to choose between the two ideologies, but prefers to have them both at the same time. They want security, which is a diffuse size, yet to touch and feel – and at the same time they want to take account of Palestinians and human rights. Of course, if you take your senses into full use, these are incompatible sizes, but that's the sad reality of the day – and the reason why it somehow makes sense when Netanyahu and Gabbay seem to be talking with the same mouth, even though they basically represents two strongly divergent ideologies.

Therein lies the damned blessing of victory, or – in the author's wording – the impossible of Israel catch-67.