(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Book essay based on Knut Ødegård Edda poem, bands I – III (Cappelen Damm, 2013 – 2015) and Gerður Guðjónsdóttir si Blóðhófnir (Language and Culture, 2010)

The porch faces Hjertøya. The heart island is the heart shape. One must be loud to see it; must be higher than she comes, Gerður Kristný Guðjónsdóttir, where she stands on the porch of room 219. She does not know that the island has the shape of a heart. Nevertheless, the hoist lifts and captures the view. The island is a narrow strip between Fannefjord and the sky. I see it, as I sit here and write on the balcony of room 319: From here I see the screen of Gerður's ipad, as well as a sky dark of rainy Møre clouds.

New meaning. Water mirror is a pervasive image in Gerður's interpretation of skírnismál. Eddakvadet's original perspective was from top to bottom: God Frøy looks down on Jotunheimen. He falls in love with Gerður, whom I call for the sake of order by the Norwegian Gerd. For hundreds of years, people read the song as a beautiful love story. Made them interpreting Blóðhófnir is seen from the earth, from Gerd, which is reflected in ponds: Roe fish in still water / played in / my mirror image // moved in one ear / out the other. The mirror image changes after marriage and is forced into: I reflected / my dead mine / in the animal's eye. She meets herself first. The page of the governor: In the doorway / I met Frej / He mirrored / his dead mine / In my eye.

"Kvada is given new meaning every time they are rewritten," Knut Ødegård says later this day – September 4, 2015. There are more weeks until he turns 70, and the Bjørnson Festival celebrates the mold poet. Change Ruset presents poems in a selection that he (Ruset) has collected. But this year, Ødegård is also releasing the third band of new edda by Edda. One of the quads is skírnismál, where Frøy sends Skirni from the goddesses to Jotunheimen to release to Gerd. Gerd thanks no to Frøy's courtship, and to the jewelry he offers. Gerd is a piece of jewelry before – of the love of her father, a strong and steadfast jotun. But Gerd becomes compulsive with Frøy. Here ends the original text.

In 2010, Gerður Guðjónsdóttir was nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize for interpreting the quad. Blóðhófnir – "blood stallion" – you describe nights of powerlifting. The idea of fatherly love and protection helps Gerd to endure them. For her thoughts they never get. Jotun women are protected by some to right to something. What are the important things to right? What gives me peace, here at the Bjørson festival – that I am home in the county where I grow up? That I am among colleagues at a literature festival? Or that I got the new one Edda? Kvada makes Norway big like the Nordic, and "me" big like a jotun woman.

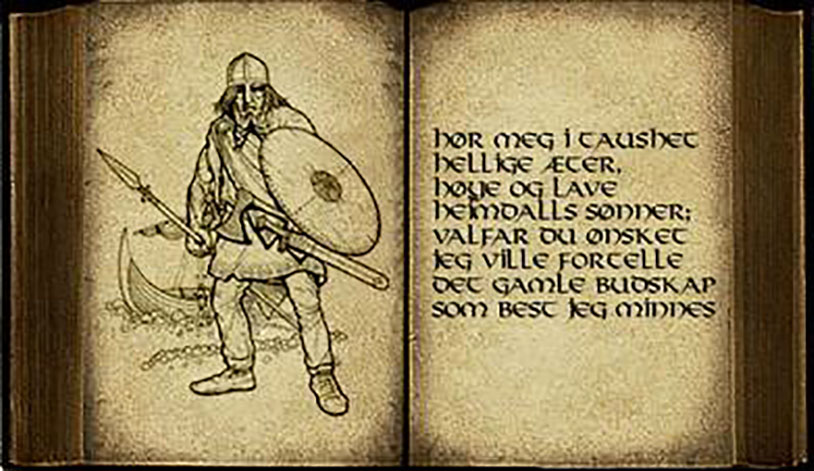

One short essay on Edda. The oldest oak tree is from before 800 AD, from a few hundred years before Norway becomes Christian. This is how Christian thinking and traditions change the country: Norway's people distance themselves from the old Norse culture. The Icelanders, well, in a democratic way, Christianity. The country is formally Christian, but not yet Christian: Iceland stands farther in the Norse tradition.

One short essay on Edda. The oldest oak tree is from before 800 AD, from a few hundred years before Norway becomes Christian. This is how Christian thinking and traditions change the country: Norway's people distance themselves from the old Norse culture. The Icelanders, well, in a democratic way, Christianity. The country is formally Christian, but not yet Christian: Iceland stands farther in the Norse tradition.

Today, Åsatrua is the fastest growing religion in Iceland. And it is in Iceland he cages, Knut Ødegård. The original manuscript is also available Edda; Royal Code. Knut Ødegård goes straight to the original. So did Ivar Mortensson-Egnund between 1905 and 1908. But a lot of our research has been written on Mortensson-Egnund's edition. It does something about the way Ødegård interprets Royal Code on. And that makes Ødegård fill in Royal Code their voids in a special way. Not least, it shapes Ødegård's reading. In one of the post he writes that more quad is about marginalized sexuality. One margin is Åsgård: Here is Frøy with its huge phallus. But what will he do with the limb up there in the deity? Frey directs his desire for a man of soft flesh and blood: Gods call on earth.

skírnismál will be called a conversation poem. Great poetry, despite the somewhat didactic form of questioning and answering. Gerd's quad is "lukewarm". When Skirni does not want to say, he trolls in "magic spell". These are both manipulative, violent; goes from above and straight down. The ruling technique is certainly not easy to detect when one is affected.

Poaching (poetry) and magic are poetry. One lead hat has two parts. Each part has three lines, with two or three strong spellings. They have a letter strip. The last word is often a one- or two-letter word, and is the strong word; the important thing: Strong is the doorstep / as the turnaround should / and open to everyone. / Do you have to make a noise / rings, or else you expect to hurt.

Magical Law is also a verse form. Each half penalty has an extra line. Letter trimming, not end trim, gives the verse power. Eddakvada has a freer shape than the one-strap shape. The frameworks that best unleash creativity.

Gerður Guðjónsdóttir was born in Reykjavik in 1970, and is a journalist before becoming a writer. She publishes poetry and prose for children and adults – but whatever she does, it's genre-conscious. Dictate in Blóðhófnir is shorter than leaded, and may be left alone. The work becomes a series of cuts. These are targeted and concise: Frey's abuse is rewritten for precise, surgical procedures. But stunning is not the case: The giant body does not protect Gerd from knowing. Each side is a wound; sensitivity materialized in an object, in a book. Jotun woman Gerd is trusted with a great masculine power, against phallus – a sword that «the journeyman brought forth […] hardened in hatred // the shaft cut by cruelty". Gerd looks great at everything. In the haze, the landscape is without detail; everything becomes clear, whole molds. From the haze comes the true words; A phrase, the top two, for a quarter of emotional impact.

Blóðhófnir is, in the size-distorted category, a "small but large" book. Short poems, to be mistaken for lead hate – but Gerður's poems do not follow the old forms. It is not the lack of knowledge that is the cause. Already owning her first poem, those who wrote as seventeen to eighteen, follow the rules. Gerður does not want to be bound to a particular form. This is how the poet practices the freedom that she has of the heroine. Gerður holds alliteration and rhythm. Blóðhófnir is therefore read as a work between modernism and the Eddictic. "This is not an unfair reading," comments Gerður laconically when I confront her with this.

One short essay on short form. Printers by Edda are playing. Get judged Poverty issues: It is disabling in the same way as when children tell. Bigger than the kid himself. The text is clearer than the one he has written down. Regin and Fåvne are brothers. Regin urges Sigurd to kill Fåvne. Sigurd sticks the heart to Fåvne, and puts a finger into it to know if it's pierced. When Sigurd tastes sheep blood, he realizes bird language. The birds tell Sigurd that Regin is disloyal. Sigurd cuts off the head of Regin. With the sword in his chest, Fowls came to Sigurd: «What kind of guy are you eating, you who dye the sword in the blood of Fåvne?"Sigurd must come up with an answer. For when the dying man calls, then one answers. Otherwise, gods throw a curse on one. Skirni curses Gerd: «You are hosted as a thistle / down / towards the end of the skuronna, "Says Skirni. He reduces Gerd to weeds. The name Gerd can mean "enclosed land or field". "The goal of a woman to be without a man if she does not accept the person who has offered her marriage goals is to find more cities in ancient quarters," wrote Ødegård in a note to the sentence. And add: “The last part of the penalty can show you something old advice against weeds in the field. "

Forcing or opening. This is divine rhetoric. I seek powerful help to encode the language of power. Former President of Iceland, Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, wrote the foreword to the first band of Edda Kvad; that with Håva goal og Voluspa. Here hero Vigdis Voluspa emerged as the greatest of all edicts. Vigdís calls Volva's divination for "advanced poetic absurdism". The poem is, according to Vigdis, "filled with great wisdom and kindness". No one knows for sure the woman who has written the vinegar vada. But exactly Voluspa there are many researchers who claim that a woman is behind. Surely I see that these poems more often ask questions that leave room for me as a reader: Did they see what they did / in the stride streams / perpetrators / and murderers / and the one who forcibly stole / someone else's / Where sick Nidhogg / merciful bodies / wolf slept in corpses / Do they know enough, or what?

Baptism today. In a lawless society, the right of the physically large is to be owed. The Vikings lie with their wives to smother their wives. But Iceland is early on with a functioning thing, a king, and a society where the law is equal to almost everyone. Gender roles change: Woman becomes less of a weapon for men. Men do not have to be physically strong to be right; Having word power becomes even more important. Human civilization is accelerating. The God himself Seeds need people of flesh and blood.

The poet of skírnismál has sincere faith in human worth. But writing, he probably couldn't. Kvada was found in Iceland – but they contain both reindeer, squirrels and herons; animals that were hardly found in the country at that time. Such details and facts are in the notes in the most recent Edda.

Ødegård and Gerður's mediations of the quad complement each other. We can see it whole, from all angles. Not only from the different heights and floors, but also from the different stances. We have the philologist's perspective from the 1905 edition. We have the poet's perspective; her gaze with the ipad, ho on the balcony of room 219. And then there is Knut Ødegård's edition: He does not carry with him the language – his poet – in the new edition of Edda. He knows the fabric and the culture well. So good that his notes have a clumsy, striking style. "The nicest of them all," writes fellow colleague Endre Ruset in a warm, raw essay about Ødegård in Romsdal's Budstikke this day, at the Bjørnson festival. I hasten to add: Perhaps the coolest too. It is going to pondus to meat with the Norse goddesses their bile layers.

Karlsvik is a writer, journalist and Norwegian responsible for TV2 School.

mette.karlsvik@gmail.com