(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Asger Jorn:

The extreme phenomenology of aesthetics

Pax publishing house, 2017

What is aesthetics? It has been a while since the term was synonymous with the doctrine of the beautiful, as rhetoric has long since lost its status as a guide to eloquence. Aesthetics is a somewhat loose discipline within academia – because although there are good textbooks and anthologies, aesthetics is in many ways exposed. Analytical philosophy destroys it (like everything else), it is quickly swallowed up by commercial or institutional interests, it somehow does not find its libertarian place anywhere, even if, like many other humanities, it receives a certain amount of attention as a kind of entertainment. On the other hand, there is no doubt that aesthetics as a discipline, subject offer and room for reflection provides a rare opportunity to discuss interdisciplinary, existential, radical and creative issues. One who knew how to grasp the many possibilities of the concept of aesthetics and to take it in was the Danish multi-artist Asger Jorn (1914–1973).

What is aesthetics? It has been a while since the term was synonymous with the doctrine of the beautiful, as rhetoric has long since lost its status as a guide to eloquence. Aesthetics is a somewhat loose discipline within academia – because although there are good textbooks and anthologies, aesthetics is in many ways exposed. Analytical philosophy destroys it (like everything else), it is quickly swallowed up by commercial or institutional interests, it somehow does not find its libertarian place anywhere, even if, like many other humanities, it receives a certain amount of attention as a kind of entertainment. On the other hand, there is no doubt that aesthetics as a discipline, subject offer and room for reflection provides a rare opportunity to discuss interdisciplinary, existential, radical and creative issues. One who knew how to grasp the many possibilities of the concept of aesthetics and to take it in was the Danish multi-artist Asger Jorn (1914–1973).

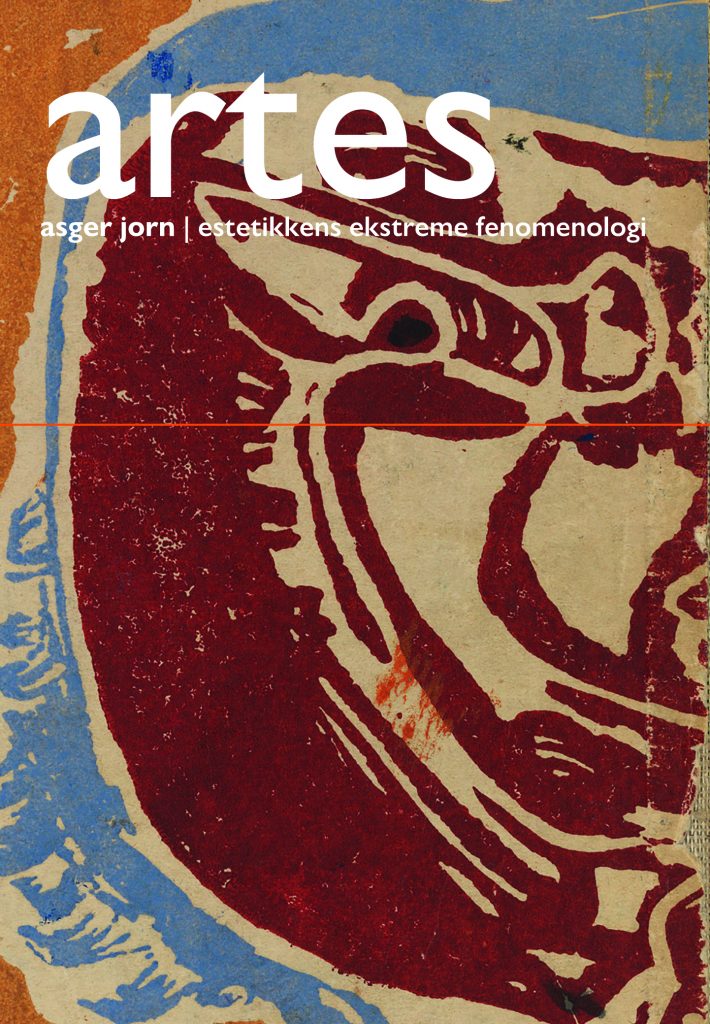

Scams and trivia. In line with the growing interest in Asger Jorn as a visual artist, in Europe as well as in the USA and exemplified by last year's exhibition "The Open Hide" in New York and "Jorn + Munch" in Oslo more recently, interest in his written works is also increasing. In the impressive series Palimpsest at Pax Forlag, the stage is now set for a selection of Jorn's art theory, called The extreme phenomenology of aesthetics. Most of it is taken from the main work Hell and hazard, dagger and guitar (1952), and a total of 36 of the eighty fabulous, small linoleum cuts from the original edition of the work are here respectfully reproduced, in bright colors and on good paper. It provides a closeness to the fabric that no screen can replace. At the same time, the format in the Palimpsest series is roughly the same as for the paperback edition Luck and chance from 1963 – and as the releases The order of nature, Value and economy og Things and police, also those represented in the text selection.

The extreme phenomenology of aesthetics opens with the manifesto "Intimate banalities". It was published in 1941 in the art magazine Helhesten, which was published with nine issues during the first war years in Denmark. It is a well-written and well-informed manifesto, full of brilliant paradoxes and striking statements: "A great work of art is the perfect banality, and the fault of most banalities is that they are not banal enough." As the title says, it is not the intimacy that is banal, as with Freud – but the banality that is intimate. The banal is closer to us than we might like, but it is crucial for art, according to Jorn. The attitude is exactly the opposite of the one we find in the American Clement Greenberg's famous article from 1939 on the avant-garde. Jorn pays tribute to amateur orchestras, rhymesmiths, tattoos, trivial glossy pictures and scam art in his search for the basic and the primal, rather than the cultured and predictable. It is in this context and in line with the interest of the time for "primitive" art that we must see Jorn's project of emphasizing Nordic folk aesthetics over the refined southern European one.

Rejects Kant. By mistake, an oft-cited section from "Intimate banalities" has been omitted from the Norwegian selection. It should be inserted before the passage about children's exemplary enjoyment of glossy pictures, and reads like this (cut it out and use it as a bookmark on page 13 of the Pak edition):

"Those who seek to oppose the production of flea market pictures are enemies of the best art of our time. These forest lakes in thousands of living rooms with yellow-brown wallpaper belong to art's deepest inspirations. It is always tragic to see people striving to saw off the branch they are sitting on."

But the slip opens a loophole into Jorn's world. Flea market pictures, or more precisely scam art, kitsch paintings, smears, banal depictions of moose in the sunset and so on are what Jorn calls in Danish "drum hall pictures" (named after the street Trommesalen in Copenhagen, where a lot of trivial art was sold). It is precisely such images that Jorn himself uses twenty years later in two important avant-garde historical painting series, with overpainted fraudulent images called "modifications" and "disfigurations", exhibited at the Galerie Rive Gauche in Paris in 1959 and 1962 respectively. Among the most famous and now priceless works of art are The disturbing duck og The vanguard never surrenders ("The unsettling spirit" and "The avant-garde never surrenders"), both reproduced in the book's photo appendix.

Then follows an extract from Hell and hazard, dagger and guitar, which is of a slightly different cast. Prestsæter's publication takes its title from this, and it is a good choice he has made here: "The extreme phenomenology of aesthetics" is a phrase that opens the preface to the 1952 edition of the work. A lot revolves around the aesthetics understood as the unknown, also in the disputes Jorn leads with Kant (with whom he settles) and Hume (with whom, with his emphasis on experience, he is probably most aligned). Jorn believes that Kant's definition of the beautiful as "general, disinterested and necessary pleasure" must be rejected, as pleasure "is really nothing other than a kind of interest". Aesthetics is the interest in the new and unknown, and the subject a sphere of interest, in a good Lacanian sense: The subject is "composed of several selves, which in turn are bundles or groupings of subjectivity". No, you are never lonely at Jorn's. He invites to a community.

The banal is closer to us than we might like, but it is crucial for art, according to Jorn.

Central actor. Like Adorno, Jorn has sentences that are in themselves rich crossword puzzles. He writes in a juicy, Nietzschean and Kierkegaardian style, where precise discussions are spiced up with twisted versions of proverbs, teachings and well-known doctrines, and where what may seem contradictory, naturally and completely consciously, is precisely that. This also applies to the contradictions of contradictions in a kind of multi-part dialectic – a "triolectic", as he himself called it. Jorn thus operates with a myriad of extreme phenomenological definitions, with aesthetics ranging from meaninglessness and cynicism to crime and possibility; from fanaticism, luxury and risk to intoxication, liberation and experiment; from sensuality and passion to illness and neurosis – to name a few.

In the chapter "I'm just a human being on clay feet", the summary reads:

"Let us state that aesthetics is a disease in the universe, in nature and among men, but not a fatal disease, not a decadence of old age, but a birth disease, a life risk, a life disease that feels like an eternal longing, and therefore can never be eradicated , but always and without interruption must be healed, as we satisfy hunger and thirst."

Can it be said more clearly? In a well-arranged and media-politically dangerous topical chapter i Value and economy Jorn has a consolation for those who are idle: "Idleness is the root of all art." IN Things and police he posts about the history of vandalism, and i The order of nature about triolectics and about Niels Bohr's quantum physics (Jorn's criticism of Bohr has also garnered recognition from prominent American physicists).

That Jorn was central to the establishment of the artist group Cobra, the Situationist International, the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus and finally the Scandinavian Institute for Comparative Vandalism underlines his important role in our recent art history. This collection of texts shows how Jorn's thoughts have acted as a glue for his creative network.

Explosives. Ellef Prestsæter has made a fine effort with his selection and his competent afterword. The translator Agnete Øye has largely succeeded; initially only a few blemishes (but where did the translations of Baudelaire and Rimbaud come from?).

Other Jorn texts could of course have been included, such as "Tale for the Penguins" (1949), "The Twisted Painting" (1959), excerpts from Alpha and Omega, Engraved signs, About the form or Golden horn and wheel of fortune, program texts from International Situationists, articles on architecture, urbanism, handicrafts, form and design and so on – but as Prestsæter says: This is mostly available elsewhere.

We ourselves are very happy to have had this still current, aesthetic-theoretical, chaotic and existentially colorful explosive material available in Norwegian.