(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

The Australian film festival CinéfestOZ was started in 2007, inspired by a similar event in Saint-Tropez (hence the striking acute sign over the e-mail). During the following decade, the festival quickly became a popular event, with local audiences and people from the national film industry in beautiful association. The program is compact, yet eclectic, and focuses on a diverse range of Australian productions. Although CinéfestOZ takes place in a relatively small coastal town (Busselton, with 36 000 residents), it has a distinct reddish-

runner element, where new Australian films are presented in flashy premiere and compete for one of the biggest cash prizes in the film world, at 100 000 US Dollars.

At the other end of the scale we have short films like Karen Pearlmans After the Facts og The Beeman by Frances Elliot and Samantha Marlowe, both great audience favorites, and the sublime, heartbreaking 8 minute animated film Lost & Found by Andrew Goldsmith and Bradley Slabe – which, regardless of category, is arguably the most notable film in 2018.

gender Balance

In the wake of the worldwide MeToo campaign the global film industry has so decidedly turned the spotlight on women's experiences. "Gender balance" has now become key, and when the Venice Film Festival released its latest award category with only one film made by a female director (Jennifer Kent's The Nightingale) on the nomination list, the strong reactions indicated that there is still a long way to go – and that it is ending patience with old-time boys club chauvinism.

After the Facts is a homage to "real women and real work".

The importance of Oscar awards in global film history cannot be overstated, and the nomination of Rachel Morrison (Mudbound) for best photo this year excelled something that really deserved to be celebrated. For this was the first time a woman was nominated in an award category that has been around since the first Academy Award ceremony in 1929. It becomes even more remarkable when you consider that before 1967, when the category included both color and black and white. productions, the number of nominations for the photo award was always double-digit. As a record for institutionalized sexism, this is even more frightening than the discriminatory nominations (and awards) in the "best director" category – where one woman was nominated only in 1977, and only five women have been nominated in the history of the award. There is one nomination less than the largely forgotten male director Clarence Brown (1890–1987) managed to get during his work.

The honorable exception is the Oscar for Best Cutting, which was instituted in 1934: The first nomination process included Anne Bauchens, for cutting Cleopatra (by Cecil B. DeMilles). Six years later, she actually won the long-awaited statuette, for another DeMille production, North West Mounted Police. By this time, mower Barbara McLean had already been nominated – and lost – a number of times, in 1935, 36, 38 and 39. McLean, who died in 1996, remains "the second most nominated mower" in the Academy's history.

Throughout history, film journalism and criticism have been so engulfed by the director's role – largely clothed by men – that very few of those behind the camera have been brought to the limelight. But it is both possible and desirable to envisage a different approach, characterized by a wider and more college-oriented perspective, where the role of women can be significantly appreciated. The cutting job – which in Hollywood is traditionally associated with women's hands, accustomed to cutting and sewing fabrics – is one powerful key to this alternative universe.

Tribute

It is precisely this kind of notion leap that energizes Sydney-based academic and filmmaker Karen Pearlman's attempt to reinterpret and transform our understanding of the medium. She has done this through both research and texts – and in films, such as the 15 minute fiction film Women With an Editing Bench.

It is precisely this kind of notion leap that energizes Sydney-based academic and filmmaker Karen Pearlman's attempt to reinterpret and transform our understanding of the medium. She has done this through both research and texts – and in films, such as the 15 minute fiction film Women With an Editing Bench.

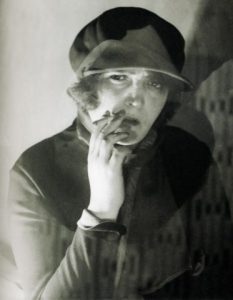

Her latest work, After the facts, enters the Soviet Union in the 1920s and '30s – and packs large amounts of insight into the fast, few minutes the movie lasts.

In the world of short films, economics mean everything, and when it comes to what we might call short-short films (less than 10 minutes), every picture and clip has a crucial bearing. If short films are like poems, short-short films are haiku poems and can be destroyed by one single misplaced syllable. The crucial importance of the clip is the core point of After the Facts – a brief and sharp shock of a movie, which sends a laser beam of limelight on the half-forgotten but truly innovative Soviet mower and director Esfir Shub (1894–1959).

Shub was a well-regarded cutter from the early 1920s when she collaborated with the great Sergei Eisenstein in the state-run film company Goskino, but is now best known as the director of the brilliant full-length feature film The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty (1927), which consists of reporting sequences. Her career stretched into the 50s, but was compromised by Stalin's displeasure. Pearlman's film highlights the contrast between what she calls with stealthy news "Stalin's sense of alternative facts", And the journalistic and objective ambitions (" real pictures of real people ") of Shub and her closest co-workers, Jelisaveta Svilova and the famous Dziga Vertov. Vertov Man with a Movie Camera (1929), virtuously cut by Svilova, has its fixed place on the list of the foremost documentaries and greatest silent films ever made.

After the Facts provides a vivid snapshot of Shub's radical attitude to assembly at a time when the film as an art form was still in its most labile and unfinished phase. Fun and insightful, with a quasi-industrial soundtrack by Caitlin Yeo, it is a hommage to "real women and real work" who, in an inspiring way, refuse to follow the conventional, handed down wisdom of the canon of living images.

The power of simplicity

One of the other major audience favorites among the short films at CinéfestOZ was The Beeman by directors Frances Elliott and Samantha Marlowe (cut by the latter). The movie is a clever and absolutely wonderful miniature about Perth's Carl Maxwell, an expert on bees. Maxwell is a good-natured, chubby guy with a quirky (possibly Dutch?) Accent, in his late thirties or early forties, communicating in almost mysterious ways with bees – his job is to preserve the species, by saving one endangered swarm at a time. "See how they stick to each other and help each other," he says with wonder as he gently and happily fiddles with a wax cake covered with bees, and scribbles convincingly about "the power of innocence, the power of simplicity."

The global decline in insects has long worried ecologists around the world, but Australia has so far proven pleasantly immune to the disaster. When you look The Beeman, one can get the impression that this is due to the convivial Carl Maxwell, who happily zooms in the sunny west Australian suburbs, in search of his next bi-rescue mission.

The film is made as part of an initiative supported by the City of Vincent, an area of local autonomy in Perth. The area is nonetheless distinctly Australian; the laid back and sad-

solve the attitude of life that shines through, matches what David Thompson called "the epic riddle" that Australia is.

"Every little detail of the earth is absolutely marvelous," Maxwell exclaims at the end of the film as he takes on an aerial voyage using a whimsical technical device that allows him to enjoy his boundless majestic land. His rejection of gravity is irresistibly enjoyable: Ladies and gentlemen, we hover in space.