(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

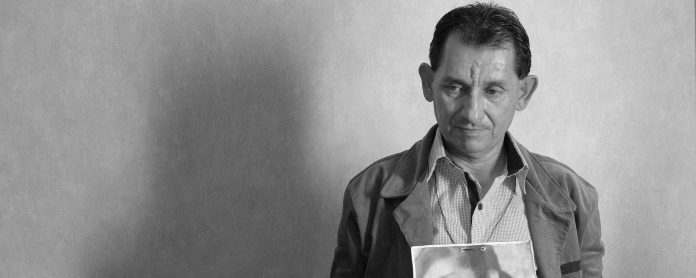

"I want to be like Superman," says the owner of a billiards hall in Guerrero toward the end of Julien Eli's documentary Dark Suns. For the past five years, he has spent his spare time looking for the body of his brother, who was kidnapped. Infrared super powers would have given him the opportunity to see through the soil layer and made the shovel and grip redundant.

But it is not the work of the search that worries him. Looking for a family member is dangerous; the number of Mexicans who have disappeared is so many that he risks excavating other remains than the brother he is looking for.

The remains belong to other families' dearly missed relatives, but for the corrupt people who have buried them, this is just unpleasant evidence – and the billiard hall owner is constantly threatened with life.

We see him find a shoe, with his foot inside. The shoe is size four or five and may not be the brother's, but belongs to one of the 32 other reported missing.

His longing for superpowers, an imagined and unattainable fantasy, underscores just how helpless he and other residents are, where they are trapped in a reign of terror between organized crime and the authorities.

In his back pocket he has a copper horseshoe, partly to bring him luck, and partly to allow the family to easily identify him if he too disappears.

He is one of several witnesses in this protracted and depressing film; an accumulation of suffering that, by its scale, shows how pervasive the threat of violence hangs over the people of Mexico.

Voices without Eco

Dark Suns is elegantly filmed in black and white, respectfully restrained and never sensational, and it allows the fear to build up in the spectator.

The film starts in Ciudad Juárez, one of the most populous cities in Chihuahua, and notorious for its brutal cartel-related crime. At one time it was the world's most violent city, and since 1993 it has had an epidemic of female killings. Hundreds of women have been murdered, obviously without consequences, a phenomenon added to an original protest against the NAFTA agreement, but which has evolved into killing people almost as a sport. The perpetrators are linked to organized crime and therefore enjoy some protection.

"It's like in the military," says one resident. "You are either summoned or killed."

"We don't do the job the authorities don't want to do," says a group of women from the organization Voces Eco (voices without echoes), relatives looking for relatives in cases where police do not appear to be doing much.

The film continues in Ecatepec. As women killings became widespread across the country, Ecatepec has become the most dangerous place in the country for a woman, we are told. Like Ciudad Juárez, the city has a predominant proportion of poor factory-working women; many of them are trapped in the town square or in the poorly lit streets and disappear without a trace.

Vulnerable illegal migrants

Transport of illegal migrants is an important source of income for organized criminal gangs, and migrants are particularly vulnerable. There is a suspicion that the drug cartels are cooperating with US authorities to curb the migrant flow to the United States, which is important for US foreign policy.

Police officers and taxi drivers receive bounties to capture migrants and surrender them to the authorities. In addition, migrants can easily end up in disputes between rival cartels, which not only compete for the drug market but also engage in extortion and kidnapping. 72 unregistered migrants were regularly executed by the Zeta cartel in 2010 in connection with a quarrel over territories between the cartels.

In a country where many Mexicans are tortured and killed in unimaginable ways, the people suffer a constant fear – although they are still alive, but forced to work for the cartels, separated from their families and not allowed to contact them .

We hear of a young man being assigned a police uniform with a message to patrol an area to prevent others from entering. Some women are forced into sex slavery. "It's like in the military," says one resident. "You are either summoned or killed."

No one escapes the threats

Neither are journalists safe. In Mexico City, photojournalist Rubén Espinosa, who covered protests and riots, found brutally tortured and killed along with four women in an apartment in 2015. He had traveled to the capital to escape the more dangerous areas of Xalapa and Veracruz, where he worked under increasingly frequent threats.

Looking for a family member is dangerous; the number of Mexicans who have disappeared is so many that he risks excavating other remains than the brother he is looking for.

The many crimes we hear about Dark Suns, gives us a growing and inevitable sense of claustrophobia. We are left with the impression that while the massive burden of dead and disappeared is enormous, it cannot be compared to the burden inflicted on the living – not a single inhabitant escapes this siege, and everyone goes with a knot in the stomach of fear of who will be the next to be hit.

At the same time, we realize that there are many who oppose this "silent regime of terror," where the truth cannot be suppressed. Parts of Mexico are a huge mass grave "with a smell you can't get rid of," we hear. A gruesome observation, but also a reminder that memory does not die so easily.

Translated by Iril Kolle