(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

It is said that if men do housework, it is usually vacuuming or something else noisy, for God forbid that they should do something that no one sees or hears. Bogen 365 Days of Invisible Work tries to make visible the invisible work and at the same time questions what counts as work. A Silvia Federici quote from the 1970s Wages for HouseworkOn the first page of the book, the campaign sets the tone: «We have been working in isolation at home when you needed it, and we have taken another job when you needed it. Now we want to decide for ourselves WHEN we work, HOW we work and WHO we work for. We will be able to choose NOT TO WORK – just like you. ”

365 Days is about housework, and housework has become a bit hipster, as is Federici. The question is who wins on that gentrification. My guess is that these are not domestic workers.

In your own or someone else's home

The book's backers (yes, men) are "Marc and Rogier from the Werker Collective," who, with false modesty, present themselves in what might well be called the book's preface. Marc and Rogier – who, of course, appear by full name in several places in the book, as opposed to those who have taken the book's 365 photos – are well-established artists who both teach at the Gerrit Rietveld Art Academy in Amsterdam. Thus, people whose work is far from invisible. They have, by their own words, developed the book together with "several self-organized trade unions for migrant workers", and the photographs were collected by amateur photographers who call themselves the Domestic Worker Photographer Network. Therefore, one would think that the book was primarily concerned with the work that some do in the homes of others, often far from their own. But no. The vast majority is about the work that people who identify themselves as cultural workers of different kinds do in their own homes.

The book's backers (yes, men) are "Marc and Rogier from the Werker Collective," who, with false modesty, present themselves in what might well be called the book's preface. Marc and Rogier – who, of course, appear by full name in several places in the book, as opposed to those who have taken the book's 365 photos – are well-established artists who both teach at the Gerrit Rietveld Art Academy in Amsterdam. Thus, people whose work is far from invisible. They have, by their own words, developed the book together with "several self-organized trade unions for migrant workers", and the photographs were collected by amateur photographers who call themselves the Domestic Worker Photographer Network. Therefore, one would think that the book was primarily concerned with the work that some do in the homes of others, often far from their own. But no. The vast majority is about the work that people who identify themselves as cultural workers of different kinds do in their own homes.

The cultural worker's rather logical preoccupation with his own ability to make noise overcomes the book's radical potential.

Working in your own home or at home with friends and colleagues in order to (become) visible is – I would say – something radically different than working in strangers' homes, where the whole point is that you have to (to) become invisible. Werker Collective tries to treat the various forms of work that take place in the home together, and they have a mission with it – to develop a "critique of 'everyday life' as we know it" – but it is not quite successful.

Absence of housework

The differences between the work of cultural workers in one's own home and the work of domestic workers in the homes of others can be read in the ways in which domestic work is portrayed: the domestic worker photographs show the wear and triviality of domestic work (for example, raised feet); organization and unity among domestic workers (production of protest materials, public assemblies); the often unworthy conditions to which domestic workers are subject (a non-taken photo from break because breaks can only be taken on the toilet, or a laundry room that is also the domestic worker's 'private' room).

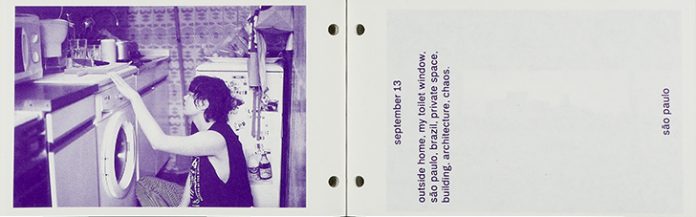

Several of the cultural worker photographs, on the other hand, show a rather obsessive absence of housework (unmade beds that serve as an office, dirty run-down bathrooms, untouched dishes); play with housework (someone lying with their upper body inside a washing machine, someone posing flirtatiously across an ironing board – the photographer for this picture calls himself a «bed nest», but I wonder if that's a fine word for cultural work); exoticization of housework (when the cultural workers actually do the dishes – or are close by – or even pack and build their exhibition materials, one senses that they are quite impressed with themselves).

Several of the cultural worker photographs, on the other hand, show a rather obsessive absence of housework (unmade beds that serve as an office, dirty run-down bathrooms, untouched dishes); play with housework (someone lying with their upper body inside a washing machine, someone posing flirtatiously across an ironing board – the photographer for this picture calls himself a «bed nest», but I wonder if that's a fine word for cultural work); exoticization of housework (when the cultural workers actually do the dishes – or are close by – or even pack and build their exhibition materials, one senses that they are quite impressed with themselves).

One of the cultural workers who contributes in a more relevant way is «daniela» (Daniela Ortiz), who has put together a series called 97 housemaids, of which a few are included in the book; the series shows «Peruvian upper class in everyday domestic situations. In the background of each photo you can see either a silhouette or a blur of a domestic worker ».

Agreed session

365 Days is organized as a kind of loose-leaf calendar – oblong with holes at one end, which lends itself to having it hanging on the wall and tearing a leaf off every day, starting with 1 May. On the front of that magazine is a text and a title, on the back the corresponding photo. On some it is clearly the photographer himself who has written the texts, on others it is more questionable. Perhaps it is Lisa Jeschke and Marina Vishmidt who are listed in the colophon as lyricists in the abstract sense. The two stand – unknown for what reason (it is not explained who they are and why they have been asked to contribute) – for the only coherent text the book contains: an e-mail correspondence under the heading «Work breaks us, we break work ». It is a somewhat agreed-upon session, which among other things refers to a play that one of them has written.

However, the correspondence has its moments, including a description of the type of middle manager who gets hurt when colleagues organize ("I thought we were friends"), and a brutal analysis of the ideology of the small entrepreneur who capitalizes all his resources – social, material, for example via Airbnb – and ends up «making income-generating activities seep through all the pores of personal and social life». It's just not very clear what it has to do with the conditions of domestic workers.

The noise without the anger

Werker Collective and their friends (?) Are probably genuinely preoccupied with examining what work consists of, what counts as work, what relation the value of work has to who is referred to perform it or where it is performed. All the more unfortunate that the cultural worker's – quite logical – preoccupation with his own ability to make noise overwhelms the radical potential that could have been in a book that wants to "draw attention to the hegemonic structures that make reproductive work invisible" , and «start visualizing counter-hegemonic ways of organizing life and work».

If men do housework, it is usually vacuuming or something else that is noisy.

The Domestic Worker Photographer Network is clearly not a network made up primarily of domestic workers, but of cultural workers who are fascinated by domestic work. For those interested in houseworkers' own photo-documentary traditions, the two Filipino migrant houseworkers and photographers like Joan Pabona and Xyza Bacani are more obvious places to start.