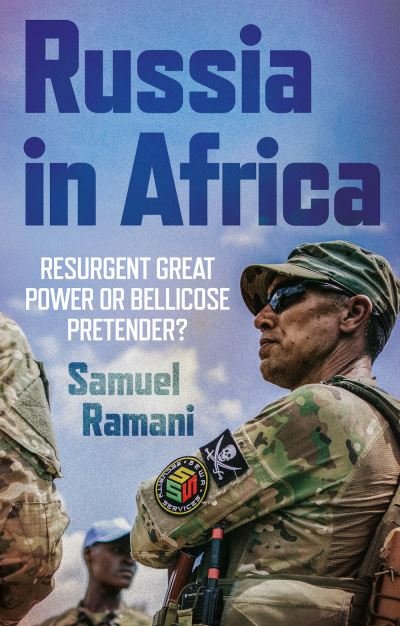

Russia in Africa

AFRICA / Russia has been very keen on the principle of non-interference and has allowed authoritarian regimes to pursue their own policies without making any political demands for their trade or aid. But they gave debt relief to a number of African countries at the same time as signing several military-technical agreements.

(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

This article is only available proofread by us

in English at Modern Times Review – just click.