(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

From Orientering 11. Nov 1967

Two excellent Sartre books were published this fall: Walther Biehmels Sartre in Cappelen's owl series, and "Jean-Paul Sartre: Political Writings," a selection by Dag Østerberg. The two books complement each other, while Biehmel first and foremost treats Sartre as a fiction writer and author of L ›Etre et le Neant, Østerberg presents to us, as the title says, to the political Sartre. At Biehmel, Sartre stands in an atmosphere determined by Husserl and Heidegger, in Østerberg's selection Hegd and Marx are most clearly labeled as Sartre's teachers. This does not prevent Biehmel from having a separate chapter in which he gives a summary of Sartre's article "Marxism and existentialism" (otherwise the introductory article in Østerberg's selection).

He ends his rendition of Sartre as follows: As long as Marxism bases its knowledge on outdated, dogmatic metaphysics rather than on the understanding of the living human being, as long as existentialism must continue its investigations independently, in order to "cultivate within the framework of Marxism a truly understanding realization that finds man in the social world and follows it in its practice, or, to put it another way, it follows in its self-fulfillment as the fulfillment of the social opportunities, based on a particular situation ”.

The books complement each other, but they do not exhaust Sartre. For example, it goes without saying – despite Østerberg's clips from the work – that none of them can give any impression of how Sartre is trying in concrete terms in Critique of the Reason for Dialysis to make this cultivation, how Sartre executes his own program. Another uncovered aspect of the diverse Sartre that could be mentioned is his analysis of racism. (The main ones are already in Norwegian: "Thoughts on the Jewish Question" in the Cappelen's unpopular series and "A chief's childhood" in the short story collection "The Wall"). And of course there are other things. But what is worth noting is that if you put the two books together you get a surprisingly good coverage and introduction to Sartre.

Biehmel begins his book with a biography: Sartre is born in 1905, when he is two years old, his father (Navy officer) dies, and his mother moves home to her parents where they live until Sartre is eleven years old. Sartre himself has told of his life in his grandparents' house that his role was that of the guest, the well-off, intelligent, entertaining guest. Here, like Biehmel, one can see the origin of Sartre's determination of existence, not as a gift, but as a task. We have to justify ourselves, do something. Later, Sartre attends high school in Paris and is then admitted to the famous "École Normale Supérieur" where he meets Simone de Beauvoir, who has since been his closest. After graduation and military service, he is a teacher at a high school in Le Havre (1931-36) interrupted by a two-year scholarship in Berlin where he studies Husserl and Heidegger. He then comes to Paris as a philosophy teacher at Lyceé Pasteur. He debuted in 1936 with L> imagination and then follows beat in stroke nausea, Esquisse d'une Theory of Èmotions, wall, L> imaginaire. He spent one year in German captivity and actively participates in the resistance movement. In 1943 comes Aries and Nothing and his first play, "The Flies." After the war we know him as a freelance writer and editor of the magazine "Les Temps Modernes".

Biehmel begins his book with a biography: Sartre is born in 1905, when he is two years old, his father (Navy officer) dies, and his mother moves home to her parents where they live until Sartre is eleven years old. Sartre himself has told of his life in his grandparents' house that his role was that of the guest, the well-off, intelligent, entertaining guest. Here, like Biehmel, one can see the origin of Sartre's determination of existence, not as a gift, but as a task. We have to justify ourselves, do something. Later, Sartre attends high school in Paris and is then admitted to the famous "École Normale Supérieur" where he meets Simone de Beauvoir, who has since been his closest. After graduation and military service, he is a teacher at a high school in Le Havre (1931-36) interrupted by a two-year scholarship in Berlin where he studies Husserl and Heidegger. He then comes to Paris as a philosophy teacher at Lyceé Pasteur. He debuted in 1936 with L> imagination and then follows beat in stroke nausea, Esquisse d'une Theory of Èmotions, wall, L> imaginaire. He spent one year in German captivity and actively participates in the resistance movement. In 1943 comes Aries and Nothing and his first play, "The Flies." After the war we know him as a freelance writer and editor of the magazine "Les Temps Modernes".

Biehmel then manufactures, in my estimation of educational success, a number of Sartre's themes as expressed in his fictional literary writing. In "The Fly" we meet in Orestes there

dehumanized man who descends from his high stage and takes on a task in the world. Biehmel: "Freedom cannot be said to consist in having as many open possibilities as possible, according to Sartre, freedom consists in making a decision in the awareness that this decision is your own, that you identify with it". The same theme reappears in the Paths of Liberty, where the protagonist Mathieu "saves" on his freedom. He believes in safeguarding his freedom by not committing to anything, by retreating to any decision of any significance. And life runs away between his fingers.

Sartre's version of Hegel's Herr / Knecht problem (the philosophy of "the gaze") is produced in connection with the act "Closed doors": The Lord is there and the jack is there, but the work is gone. None of the three people in the play handed to each other can do anything further to change the situation and what they themselves are, they are dead. Under this premise, the famous and controversial words Sartre puts in the mouth of one of the three: "Hell, that's the others."

One chapter is devoted to sincerity (mauvaise foi), the wonderful thing that one can lie to oneself. Man is not only positivity, it is also a transcendence or negation of this positivity, it has opportunities. The sincere player on this duality to avoid their responsibility to themselves, either by claiming themselves

to coincide with their positive stipulations ("I am cowardly, do not expect anything from me -") or by turning their negativity into their positive being and positivity into nothingness ("I am already far beyond what you think you see in me, the coward you are talking about has nothing to do with me ”). Other chapters deal with freedom relative to choice, fact, and responsibility, as well as the plays "Dead Without Burial" and "The Devil and Dear God." Besides the already mentioned chapter on Sartre's relationship to Marxism, there is finally one about Sartre as a polemic (Les Temps modernes) where, among other things. a. His obituary about Albert Camus is reproduced.

Biehmel's book does not aim to evaluate Sartre and his authorship, but to pedagogically interpret his points supported by ample quotations. He only sporadically expresses his own attitude, perhaps most clearly in the concluding remark: “The emphasis on the power perspectives on interpersonal relationships, which condemns them to failure, can easily provoke protest in us. But this is not an invention of Sartre. What he is doing here is merely mercilessly referring to an event we are constantly in the middle of… If we were to criticize his work, many of his answers and views would appear unacceptable. But what will at any time force respect on us, is the consistent attempt to grasp history and the events of human life not simply 'as

Biehmel's book does not aim to evaluate Sartre and his authorship, but to pedagogically interpret his points supported by ample quotations. He only sporadically expresses his own attitude, perhaps most clearly in the concluding remark: “The emphasis on the power perspectives on interpersonal relationships, which condemns them to failure, can easily provoke protest in us. But this is not an invention of Sartre. What he is doing here is merely mercilessly referring to an event we are constantly in the middle of… If we were to criticize his work, many of his answers and views would appear unacceptable. But what will at any time force respect on us, is the consistent attempt to grasp history and the events of human life not simply 'as

fate, but as something which according to its nature calls each of us to co-responsibility and participation. "

The selection Østerberg Presents for us can be said to consist of three parts. The article "Marxism and existentialism" forms part, "Colonialism is the el system" and "Patrice Lumumba: A political portrait" another. The third part consists of clips from "Criticism of the dialectical sense." When it comes to these clips, there may be reason to believe that they will seem rather inaccessible to the ordinary reader, although Østerberg in his preface gives a brief account of the most important concepts. Whatever it may be about it, "Marxism and existentialism" and the Lumumba article are already more than enough for the book to attract many readers. These two articles together give a very good picture of Sartre's political attitude, the first on the very principle level, the second by showing us an application of his principles and methods in the analysis of a particular political situation.

In "Marxism and Existentialism", Sartre claims that Marxism is the philosophy of our era. Marx, says Sartre, is right "both against Kierkegaard and Hegel, since with Kierkegaard he claims the peculiarity of human existence and with Hegel he deals with the concrete man in his objective reality". But what then becomes the role of existentialism? Yes, Marxism has solidified into an art of interpretation that no longer sees the particular and which seeks to return change to identity. "Marxist voluntarism likes to talk about analysis, but it has reduced this operation to a simple ceremony. It is no longer a question of studying the facts in the general perspective of Marxism in order to enrich knowledge and illuminate the action: the analysis consists solely in getting rid of the details… »Dogmatic Marxism in this way deprives itself of learning something from experience, pure contempt for empiricism prevents it from seeing anything other than the same thing repeat itself and repeat itself (albeit in other shapes and disguises). Dogmatic Marxism has the essence and the essence of history inside, he does not learn anything from the events, he only classifies them. Through this critique, Sartre clears space for existentialism. Nevertheless, he claims, "Marxism remains the philosophy of our time: it is insurmountable because the circumstances which produced it have not yet been transcended."

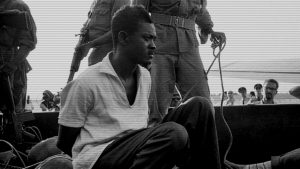

In his article on Lumumba, we see by following a concrete analysis what Sartre understands by the concepts he has elaborated in "Critique of dialectical reason": series, class, group, collective, state,… But we see more. We understand Congo's misfortune, why Lumumba could not do his job. Lumumba, the "liberated petty bourgeoisie", could put nothing but abstract universalism in the place of the unity represented by the disorganized pressure on the Belgians. The moment the Belgians were gone and "independence" was a fact, Lumumba appeared as an abstract entity – which had to come into conflict with any concretely fundamentally experienced community of interest. Everyone was against Lumumba. In this situation, foreign capital interests had easy play. And one can, with Sartre, ask oneself: why did Lumumba have to be murdered? "Imperialism does not care about human life, but since it already holds the victory in its hand, could it not have spared itself a scandal? In reality, it could not. . . The reason for this is that as long as he lived, he represented the relentless rejection of the neo-colonialist solution, which is to buy the new lords, the bourgeoisie of the new nations, in the same way that classical colonialism bought the chiefs, the emirs and the wizards ». Alive, Lumumba remains a threat to the "ideal" solution in the Latin American pattern: "a weak centralism, the bourgeoisie's (or, if preserved, feudalism) alliance with the army, the supremacy of the trusts."

In this article, we meet Sartre at his best – and most relevant, as the encyclopedic and perspective spirit that gathers the threads: the philosophical, historical, political, biographical… I think I am doing the other parts of "Political Writings" wrong by suggesting that It is first and foremost this article politically interested should not let go.