(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

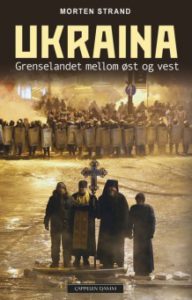

Morten Strand: Ukraine: the border country between east and west

Cappellen Dam, 2015

Richard Sakwa: Frontline Ukraine

Carnival publisher, 2015

Dagbladet journalist Morten Strand's book Ukraine – the border country between east and west is characterized by great storytelling and solid historical background knowledge. Chapter by chapter, it presents an exciting account of the development of the country from the Viking Age until today. Strand's background as a journalist shines through in that he has a good ability to communicate and a poetic language. It makes great impression to read about the famine triggered by Stalin's forced collectivization of agriculture at the beginning of the 30 years and the Nazi extermination of Jews, Communists and Gypsies ten years later. But it is also interesting to find out how the Soviet Union, before and after Stalin, encouraged the use of Ukrainian language, and that four of the secretaries-general of the Soviet Communist Party – Khrushchev, Breshnev, Andropov and Chernenko – all had Ukrainian backgrounds.

Dagbladet journalist Morten Strand's book Ukraine – the border country between east and west is characterized by great storytelling and solid historical background knowledge. Chapter by chapter, it presents an exciting account of the development of the country from the Viking Age until today. Strand's background as a journalist shines through in that he has a good ability to communicate and a poetic language. It makes great impression to read about the famine triggered by Stalin's forced collectivization of agriculture at the beginning of the 30 years and the Nazi extermination of Jews, Communists and Gypsies ten years later. But it is also interesting to find out how the Soviet Union, before and after Stalin, encouraged the use of Ukrainian language, and that four of the secretaries-general of the Soviet Communist Party – Khrushchev, Breshnev, Andropov and Chernenko – all had Ukrainian backgrounds.

One-sided understanding. Despite his solid historical knowledge, Strand still shows a fairly one-sided understanding that today's conflict is due to contradictions between a "Prorussian" Eastern Ukraine and a "European" and "modern" Western Ukraine, in addition to "aggression" from Russia . Compared to the new Swedish translation of the British Russian writer Richard Sakwa's book Frontline Ukraine he has a lopsided relationship with the facts about the complicated situation in the border country between Russia and the EU.

Richard Sakwa's book shows a writer with a much more thorough and more nuanced understanding of Ukraine. While both Strand and Sakwa spend a lot of time condemning the brutality and undemocratic features of the Yanukovych regime, Strand, unlike Sakwa, fails to mention the new, "pro-European" regime's repeated attempts to ban the Ukrainian Communist Party, and fails to condemn it. new regime's decision to face the uprising in eastern Ukraine with tanks and bombers instead of diplomacy and negotiations. While Strand takes an apologetic stance on the right-wing extremists' influence on the new regime, referring to the fact that they only received 6,5 percent of the votes in the parliamentary elections, Sakwa emphasizes that fascists took 8 of 21 seats in the new government, in addition to the important the post of head of the National Security Council.

Pluralism versus nationalism. Sakwa writes that the political background for his book is that the Ukraine crisis is "the worst crisis in Europe since the 1930s, where inflated idiots repeat well-oiled phrases while the media is filled with war cries" and that this may lead to "we go in sleep into a new war ». Sakwa claims that the current crisis is due to three conflicting visions. In Ukraine they are "orange" the western Ukrainians, who see Ukraine as one uniform nation where Ukrainian is to be the only official language, against the "blue" the eastern Ukrainians who see Ukraine as one pluralistic state and wants Russian and other minority languages to have official status as well. At European level, the opposition is between an EU that wants to expand its borders further east while maintaining its military alliance with the United States, and a Russia that wants equal security and trade policy cooperation with the EU from Vladivostok in the east to Lisbon in west, without American interference. At the global level, there is a contradiction between a United States that claims the right to spread its political system around the world, and a conservative Russia that believes that all states are obliged to follow the principles of non-interference in other states' internal affairs.

Sakwa writes […] that the Ukraine crisis is "the worst crisis in Europe since the 1930s, where inflated idiots repeat well-oiled phrases while the media is filled with war cries".

No new Hitler. Sakwa describes Putin as "the most pro-European leader Russia has ever had" and rejects claims that Putin is "a new Hitler" who wants to unite all Russians in one state. He stressed that Putin's Russia had given in to countries it had previously claimed for China and Norway in exchange for stable borders, and rejected requests from rebel authorities in Transnistria and the Donbass to join Russia. But Western violations of international law against Yugoslavia, Iraq, Libya and Syria and the ever-expanding NATO along Russia's borders have weakened Putin's original pan-European vision in favor of the Russian nationalist opposition. Western support for the coup against Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was seen as proof that the West had hostile intentions, and led Russia to choose to annex Crimea illegally to protect the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

Two views. Unlike Sakwa, Strand does not directly explain his political starting point, but he concludes each chapter by discussing whether the events he has described have made Ukraine more or less "Ukrainian". He thus stands with both legs planted in defense of the nationalist device understanding of what Ukraine should be, and is similarly suspicious of everything that comes from Russia and "pro-Russian" Ukrainians. For example, he claims, without bothering to argue for it, that "there is little doubt that the activities of retired or active people from the Russian security forces that started and organized the Donbass uprising had at least implied the Kremlin. support". This is in stark contrast to Sakwa's remarks that Putin warned against holding a referendum on independence in Donetsk and Lugansk, and that the Russian nationalist leaders of the uprising referred to Putin as a traitor.

Fact errors and use of sources. Strand is most credible when he writes about places and events where he himself has been present as a journalist. For example, it is interesting to read about when he visited the Soldiers' Mothers in Russia. According to information they have gathered, many conscripted Russians have been pressured by their officers to sign declarations that they will fight as "volunteers" in eastern Ukraine, and that they will then be officially discharged from the army. In this sense, Russia is formally right when it claims that the Russian forces fighting in Ukraine consist of "voluntary" and not regular military troops.

But at times, Strand's provincial views appear to be tendentious. For example, he concludes the book by rallied over the "lie factory" of the "Putin state" which speculated whether the murder of the regime-critical Russian Boris Nemtsov was committed by the opposition itself to blacken the regime, but fails to mention that then ten (!) Ukrainians opposition activists were killed at about the same time, representatives of the Ukrainian regime also speculated that they had been killed by other opposition figures. The main problem with Strand's book, however, is that it is difficult to follow in the footsteps. He gives a list of sources at the back of the book, but it is clear from the text which sources he has used where, and it is therefore difficult to check whether the information he presents is actually correct.

Inadequate source criticism. The problem is clearly manifested when Strand mentions the murder fire in Odessa on May 2, 2014, in which 42 opposition members lost their lives when the building they were staying in was attacked by Ukrainian nationalists. Strand writes about the 42 killed that "15 of them were Russian citizens, and five from the pro-Russian breakaway republic of Moldova, Transnistria". He then uses this as a justification to conclude that "Ukraine had become a gathering place for insurgents from outside, people who traveled there as activists and war romantics". But as early as May 7, 2014, the Kyiv Post reported that the original allegations about foreign nationals were outright false, and that all those killed were local residents of Odessa. This was confirmed by a UN report from June 2014 and a local commission of inquiry in the spring of 2015. That Strand fails to investigate such allegations, and thus ends up becoming a parrot for nationalist untruths, indicates a startling lack of source criticism which unfortunately undermines trust to the entire book project.

The critical analysis in Sakwas Frontline Ukraine should definitely be a preferred choice for anyone who wants to understand the complicated and serious situation that is taking place right in the heart of Europe.

aslakstoraker@yahoo.no