(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

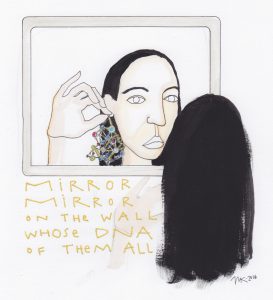

"What I am afraid of is genetic discrimination," Ellen Økland Blinkenberg told Ny Tid. Blinkenberg is a specialist in medical genetics and has written a book on issues related to genetic research, My DNAgbok. “We are sorted and selected all the time, we get grades at school and we are selected for football teams, but sorting based on genes is something new. There may be insurance companies, employers or high-level sports clubs who want to know who to bet on. After all, all the agencies that evaluate us are interested in knowing as much as possible about us, including the genome as well. ”

The pressure to map people's genes is not a trivial matter, according to director of the Norwegian Data Protection Authority Bjørn Erik Thon. "It's the code for the person you are mapping here. When it comes to whole genome sequencing, in reality everything is known about us, at least when it comes to the genetic: diseases one may be predisposed to, skill in sports, preferences for studies and perhaps even down to dispositions for crime. It is highly sensitive data to a very high degree, "says Thon to Ny Tid.

According to Blinkenberg, we are moving towards a future where we will all be able to map our genome – that is, the individual's total DNA content – but there is still a lot we do not yet know. "It's about using whole-genome sequencing where you map all the genes to a person, ie everything that's unique to that person. We are a little bit in the beginning phase, so we don't yet have a complete overview of how much the genes can say about us, but that's probably a lot, ”says Blinkenberg. The mapping of genomes can have unintended consequences as more and more are mapped and more and more associations between genes and personal traits are discovered. "To what extent will one have to browse their genome in the future as part of the assessment for, for example, admission to a school?" Asks Blinkenberg. "One thing is, if this is done out in the open, you know that you have to submit the genome to it and that insurance or admission test, but if this is done without you realizing it, then it's more questionable."

Privacy on the decline front. Kjetil Rommetveit, associate professor at the Center for Theory of Science at the University of Bergen, works to analyze the political and technological development in this field, among other things. He tells Ny Tid that privacy ended up on the sidelines when the large databases for research were to be built up. "Perhaps the most powerful biotechnological research in Norway has over the last 10–20 years been most concentrated on the large databases – the biobanks – and the possible connection of these to various public registers," says Rommetveit. "The struggle for legal regulation of biobanks and health registers has been going on since the early 2000s. Since then, and especially in the new Health Research Act of 2015, informed consent and privacy have been on the wane. "

Privacy on the decline front. Kjetil Rommetveit, associate professor at the Center for Theory of Science at the University of Bergen, works to analyze the political and technological development in this field, among other things. He tells Ny Tid that privacy ended up on the sidelines when the large databases for research were to be built up. "Perhaps the most powerful biotechnological research in Norway has over the last 10–20 years been most concentrated on the large databases – the biobanks – and the possible connection of these to various public registers," says Rommetveit. "The struggle for legal regulation of biobanks and health registers has been going on since the early 2000s. Since then, and especially in the new Health Research Act of 2015, informed consent and privacy have been on the wane. "

Researchers have a real need to build up databases with genetic information on as many people as possible. Such databases make it possible to see which genetic variations are statistically normal, and thus find the genetic mutations that lead to disease. But privacy creates restrictions. "If you want to get such a data set anonymously, you can't save anything but the exact gene variant," Blinkenberg explains. "There is a debate now about what kind of numbers to build: Should it be truly anonymized, or should it be limited? Here there are conflicts, since research interests here are against privacy interests ».

The crux of the battle is that when you map the entire genome to a human, you can no longer talk about anonymized data. “A genome is what sets you apart from everyone else, it's unique. It doesn't help that your genome is called number 7053, it's still inextricably linked to you, ”Blinkenberg explains. In the past, it has been assumed that as long as you store the genome without linking it with the name of the person it originates from, the person cannot be identified either. This assumption has begun to crack. In 2013, gene researcher Melissa Gymrek demonstrated that it was possible to re-identify people in such databases based only on genome data combined with information that was open on the Internet. Blinkenberg is critical of the way the large population surveys – such as the Mother and Child Survey (MoBa) and the North Trøndelag Health Survey (HUNT) – have mapped people's genes. “It is important that participants who are going to get the whole genome sequenced are well informed about what this actually is and that they have consented to it. Consent presupposes that one really understands what the investigation entails. I think it is under-communicated that it is not possible to anonymize a genome, ”says Blinkenberg.

Heredity and environment. However, the genome does not say everything about us. Rommetveit emphasizes that there are limits to what one can conclude about a person based solely on the genes, and will avoid that some form of gene determinism will define the debate. As gene research has made progress, it has been found that there are many factors that affect, for example, whether a disease that is genetically predisposed, spreads or not, and that environmental factors can also alter our genes – so-called epigenetics. Therefore, researchers are interested in linking information about our genes to information about everything from childhood to lifestyle and disease history, in order to understand more about the relationship between inheritance and the environment. On the one hand, gene mapping becomes less dangerous if the genes do not determine everything, but this in turn also becomes an argument for gathering far more information about other conditions in our lives. In principle, there is almost no limit to what information can be interesting to map for research purposes.

Rommetveit explains: “Until April 2003, a global gene mapping project, The Human Genome Project, was run. The researchers were to map genes to understand how they control human biological evolution, including the development of various forms of disease. In the course of research, it became clear that biology was more complex than many had imagined. In order for scientists to make sense of the vast amounts of genetic data, it was decided that it was necessary to gather tremendous amounts of information on all these other factors affecting biological. "

This has also been done in population surveys in Norway. "In questionnaires from some of these post-genome health surveys, conducted on relatively large sections of the Norwegian population, the researchers collected questions about very private matters related to lifestyle and health in addition to the genetic information. One of these is MoBa, which faced strong criticism for asking very detailed questions without informing participants about the implications of this type of research, ”Rommetveit explains.

Purpose Discs. The fact that our genes can reveal a lot about us is one thing – but what problems can actually arise when our genomes are registered? The Norwegian Data Protection Authority's Bjørn Erik Thon points out that data that is collected may end up being used for other things than what they were intended for – so-called purpose slippage. "I have ownership of my data, and it should not be used for anything other than what I want," Thon states. Ny Tid asks Thon if, for example, it could happen that the police ask for access if they build up a genetic register intended for health research. "I see this as an opportunity in the long run, because the genes say so much about us. You pull a little on the smiley face when you talk about whether there may be a criminal gene, but what if you manage to find the criminal gene, or a potential rapist or serial killer? Then it is easy to imagine that the police will also want to access the data before a crime has happened. It is a typical example of purpose slippage, ”says Thon. If the police in such a situation have a deterministic understanding of what the genes say about us, it can go right wrong.

"We're heading towards a society where we're going to be mapping our genomes to all men."

Blinkenberg also points to the possibility that databases built up with Norwegian patients can be sold to foreign researchers or commercial players. "The public health institute can sell the biobank to a serious player, but what if it is sold further, for example to an insurance company or to someone who is doing lugubrious race research or the like? Many people are interested in our genes. It is common for researchers to share data among themselves, and it has been less problematic before when you have been able to anonymize data you share. All this becomes more complex when it comes to identities. ”

Do we all become test subjects? Ny Tid has talked to a number of researchers in the field, and one thing they all agree on: We are moving towards a future where everyone will have their genome sequenced. "This is coming, there is no doubt about it. The positive thing is that we can get more effective diagnosis of rare diseases, but I do not want that development to come on a sleeping population that has not thought through the negative aspects as well, "says Blinkenberg. Despite the fact that there has been relatively little debate about the social consequences, several large projects have been launched to map and build large databases of human genomes. In the UK is 100,000 Genomes Project, which aims to sequester 100 British people, part of the public health system. Here in Norway, Torgeir Micaelsen (Ap) has called for the introduction of a similar project with the goal of surveying 000 Norwegians. "I think it's just a beginning," Blinkenberg says. "It's going to be all newborns in a few years, and it probably won't be long before that happens. It is, after all, most practical, but not undoubtedly positive. The important thing is that those who do not think it is okay to have the genome mapped and stored indefinitely, must be able to reserve. ”

Director Bjørn Erik Thon of the Norwegian Data Inspectorate believes that we have a good debate about where the boundaries should go when it comes to storing and using genetic information. "We need to make thorough assessments on how to use this and what to inform people about when conducting genetic studies. It's a mix of old privacy assessments and some new things, because it's such sensitive data, and because it's probably an area where people have little knowledge of developments, "says Thon. Ultimately, it is also important for the research that the population to be researched, informed and release their genes with open eyes. It is a known problem from the past that doctors list so-called "tire diagnoses" in the official journals where the patients have no confidence in the system, nor does a shadow journal with the real diagnoses. "I want people to think through what they want," Blinkenberg says. "We're heading towards a society where we're going to have our genomes mapped out to all men, and then it's fair that people have thought through it a bit beforehand. Should we be subjects as soon as we are admitted to hospital and a blood test is taken, or should we not? "

Tori is a journalist for Ny Tid.

tori@toriaarseth.no