(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Late in the night of April 26, 1986, reactor 4 at the Pripyat / Chernobyl nuclear power plant near Kiev in Ukraine (then the Soviet Union) exploded. The world's biggest nuclear accident was a fact. The situation, which quickly developed into an international disaster, had probably been out of control for some time.

Due to the aftermath and the abdication of responsibility afterwards, the circumstances surrounding the accident (s) are somewhat unclear, but the realization of the worst accident in the short history of nuclear power eventually reached both the audience and the heads of the Soviet party coryphaeus, led by General Gorbachev.

The flue gases from the burning power plant were over a kilometer up in the air, and during the ten days the fires lasted, radioactive material was spread with weather and wind north. explosions

The surrounding areas were hit hardest, but the lightest particles were slowly carried by the wind towards Finland, Sweden and Norway. Later, radioactive fallout also fell over large parts of Central Europe and the United Kingdom.

Miniseries

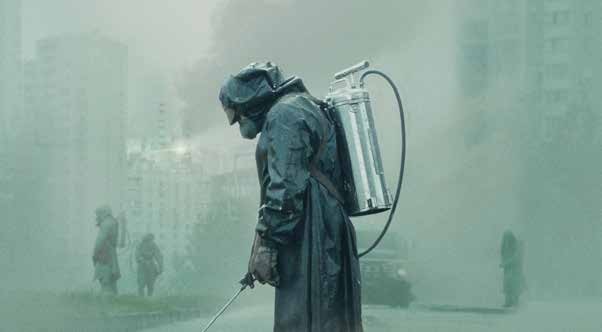

33 years later, the disaster now has its epic aftermath in the form of a television series. It is a strong and tantalizing diet, but also great docu-fiction viewers are offered when the miniseries Chernobyl these days appear on HBO. The series gives us spectacular and well-directed documentation of the events in Pripjat in Ukraine during these explosive and anxious days in late April 1986.

The Norwegian health authorities went out early and neglected the effects.

Familiar face. In the main roles, we find stars such as Stellan Skarsgård and Emily Watson, who together with Jared Harris, in the role of chief nuclear scientist Legásov, make a formidable effort on the screen. Skarsgård plays Deputy Head of Government Boris Sjerbina with rugged bravado, and in an unmade duo with Legásov, he forms the film's character-driven axis. Legásov is the intellectual, but also detached from reality researcher, who through the accident is forced to face a reality he cannot survive. He commits suicide exactly two years later.

The Chernobyl accident is considered the worst nuclear disaster the world has ever experienced. There is great disagreement about the long-term health effects. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that radiation from Chernobyl will cost a total of 9000 lives. Greenpeace, for its part, believes that as many as 100 will die as a result of the radiation.

Filmmaker Craig Mazin and director Stakka Bo have created a plot-driven film menagerie that constantly stays close to the accident, and which combines strong, expressionist retro images and environments with the sounds of a dying Soviet society. The series constitutes a coherent warning against what a technological world will bring, especially when everything that can go wrong, does go wrong, as it does in this real-life story. Mazin knows his genre references; at times it is all reminiscent of Soviet science fiction from the 70s, but the slow narrative style also allows for condensed tension, as in the scene where death-defying divers enter the reactor to open the sluice valves.

Emily Watson in the role of Ulana Khomyuk, Legásov's close colleague, radiates through her intense presence a perfect combination of human caring ability and genuine scientific knowledge, in counterbalance to both the bureaucratic power system and the cold disclaimer of responsibility of the party leaders. Through her meticulous investigation into what was the real cause of the accident, she also provides a welcome impetus to the action plot.

Information crises

Indirectly, the film also directs the spotlight on other states' crisis management and information work towards the public. As a journalist, I remember well how the Norwegian health authorities, with the Directorate of Health's new employee Ole Harbitz as one of their spokespersons, tried to calm an increasingly anxious population by under-communicating the effects the spill could have on Norway. Director of Health Torbjørn Mork and then director of the Norwegian Institute for Radiation Hygiene, Johan Baarli, left early and downplayed the effects. It is hopefully not significant that Harbitz is today head of precisely the Directorate for Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety.

Chernobyl is a plot driven movie genre that keeps itself close to the accident.

Another state agency, the Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), chose an open and far less bias-proof strategy, which resulted in NGU eventually taking on a somewhat unexpected leading role in meeting an exponentially growing need for information. Through listener funding, several local radio stations acquired their own professional measuring instruments, and they carried out a large number of local measurements, much to the consternation of local business authorities, among others, who were very poorly equipped, and moreover loyal to the Directorate of Health's misunderstood reassurance line.

NRK was also consistently loyal, but also selective in terms of who was informed. The fact that we were in the middle of a change of government, and also arranged the world final of Melodi Grand Prix right after the accident, hardly contributed to making the situation better. All those present in the Grieghallen in Bergen on 3 May, where large parts of NRK's staff were gathered, were also told, over the intercom, to keep their children indoors that day, after a new explosion in Chernobyl. This message never reached the public...

Massive denial

Skarsgård has called the series a tribute to the ground crews who sacrificed life and health in the aftermath of the accident, but it is far more than that. It is also a revelation of the massive denial and concealment that took place, under the auspices of the Soviet authorities, right after the accident, and which in Norway turned into one of the worst crises of confidence in history. Afterwards, this crisis resulted in a separate NOU specially ordered from the Storting, with the telling title Information crises, led by the pen by Gudmund Hernes. This is still interesting reading.

The series appears on HBO.

Also read: Chernobyl Victims – Gerd Ludwig's photo book