Forlag: Kolofon Forlag, University of Minnesota Press, (Oslo, USA)

(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

The magazine The Economist wrote in April about "ballistic housing prices" during the corona crisis. But, the liberal newspaper continued in the leadership position, politicians must for be pressured and tricked into introducing rental regulations and other social measures for the housing market. What we need more is liberal reforms of planning and speeding up construction – do not forget the law of supply and demand, we were warned.

The leader was as taken from the discussion about the housing market in the 1800th century. No matter how bad it went, the answer was always the same: We need more liberalization!

Bauer and modern housing policy

An insight into 1800th century housing discussions is well presented in the masterpiece of the North American housing activist and urban researcher Catherine Bauer (1905–1964) Modern Housing (1934), which was republished last year.

The book provides a detailed overview of 19th century slum formation and ungovernable urban development. When the American city is ruled by private speculators, Bauer shows, homes become both small and expensive. This society was then also legitimized through cynical liberalism, Bauer states.

However, when an American reform movement against liberalism finally emerged in the late 1800th century, it was marked by poor proposals. Bauer shows that the reformists of the past did not challenge the socio-economic paradigm. They did not want to prevent land speculation, replace private actors with social cooperatives – or introduce subsidies.

The Reformists wanted to build social housing similar to that which existed in the usual housing market. It was out of the question to have a social intermediary in the form of non-commercial housing built with the help of subsidies. Subsidies broke with the ideology of liberalism, since they made the occupants of homes built with such public funds "dependent" on the state. As if the homeowners were not dependent on the tenants – or that house price growth is created collectively by the desire to simply be present in the city? Where the ownership ideology was intended to create independent free individuals, Bauer shows that with the absence of social regulations, these homes often became more expensive each time they changed owners.

Rent-to-own is intended as part of the Labor Party's "third housing sector".

Although Bauer agrees with the reformists 'weak and short-term solutions, she also believes that Friedrich Engels' pamphlet The housing issue from that time is too negative, as it simply waits for the revolution before action can be taken. And resolute action was needed.

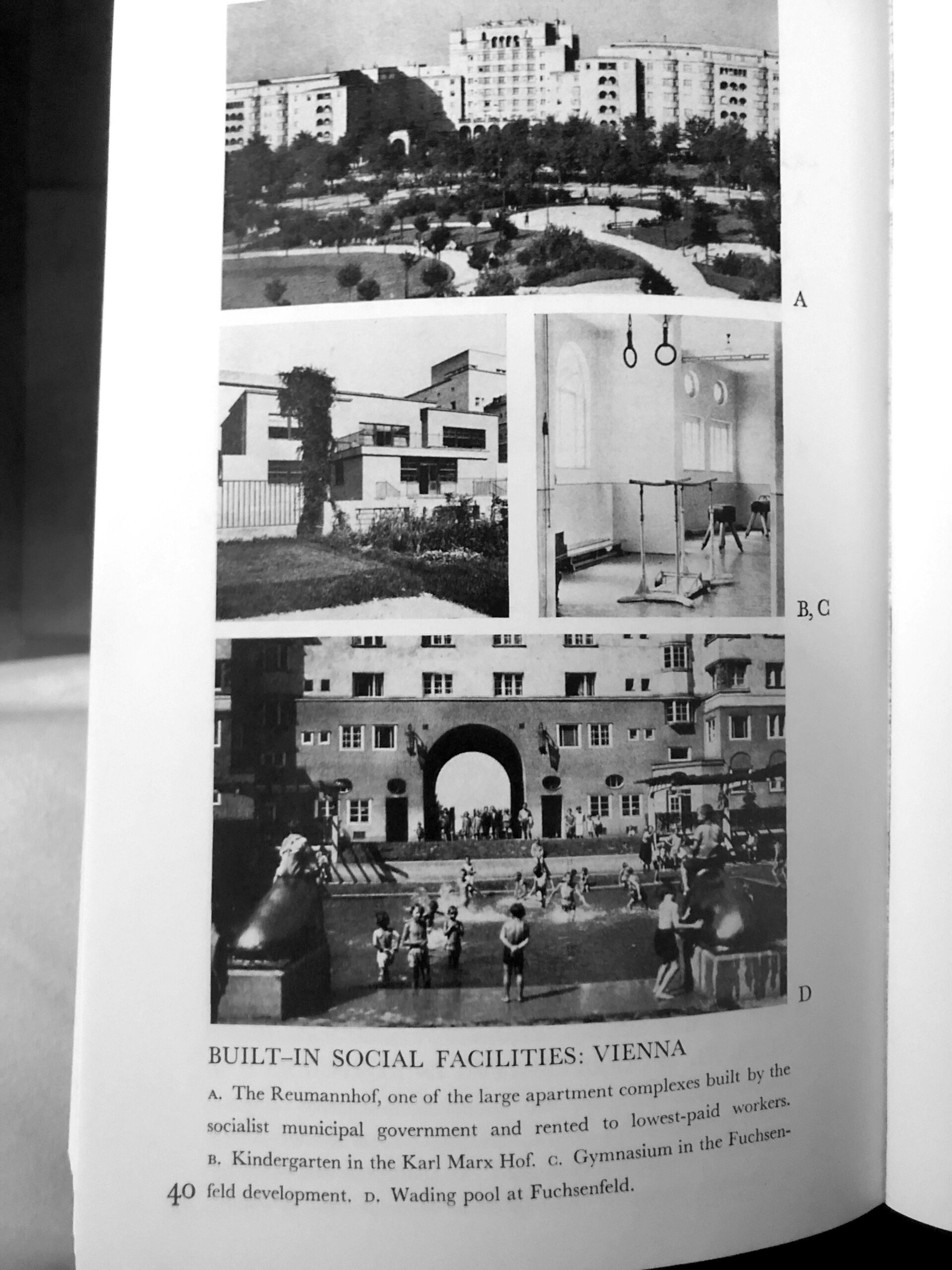

When Bauer wrote the book in the 1930s, the United States was in the midst of the Great Depression – the housing crisis was acute. The United States still had the liberal housing market of the 1800th century. Bauer believed that the solution was to be found in the growing modernist housing movement in Europe. The book is thus a painstaking review of modernist pioneers on both the residential, architectural and urban planning fronts. In the 1934 original as well as the new edition, there are as many as 200 illustrations of plans and architecture. In the book, readers could see photos of Vienna's magnificent Karl Marx-Hof with its 1500 housing units.

Although both technique and style are central, Bauer prescribes more generally that urban planners must put the social dimensions at the center. They have to think big. Vienna with its affordable rental housing was a good example in this respect. As the need for housing is constant in the big city, and it is expensive to build there because the land is limited, housing should be a public right and service offered to the inhabitants.

Claiming such a right was no easy task. Bauer therefore believed that trade unions and housing activists should form a common front for better housing.

Boysen: A fair housing policy

Bauer made an extensive trip to Europe and also visited Norway. Whether Bauer met the Norwegian architect Carsten Boysen (1906–1996) is uncertain for the undersigned. This is probable, because he was essential in the establishment of the modernist environment in Norway. Boysen co-founded Mot Dag and the group's Association of Socialist Architects and the associated magazine PLAN in 1932 and 1933, respectively. In PLAN, the housing barons were criticized, and modernism romanticized.

Already during his studies in the transition to the 1930s, Boysen and his fellow students came into clinch with the conservative architecture education at the country's only architecture education at the time, the Norwegian University of Technology (NTH) in Trondheim. Architect and housing researcher Jon Guttu's new well-written biography of Boysen shows that it irritated the politically engaged students to spend time learning to draw ornaments – in a city characterized by social inequality.

A new generation of architects would not have style teaching in one hour and construction in another – they would see it all as one. Like what Bauer wrote: "One of the most hopeful facts of both modern housing and modern architecture is that they are not two separate spheres."

Boysen and the other students 'dispute with NTH culminated in a debate in the capital at the Architects' Association in 1930. Professor Sverre Pedersen and Boysen each defended their side of the case, something Guttu devotes another chapter to: Pedersen promoted gradual reform of architecture – and thought modernism was a fashion that would disappear. Like Bauer, Boysen explained that Europe's growing modernism was a consequence of "the social shifts that have taken place and are taking place with full force" – as he said in his post in Oslo.

Boyer did not want the architect to contribute to the extravagant waste of resources of the bourgeoisie alone, but to contribute to the planning of society – and that he or she could build reasonably for the working class. Modernism or functionalism had to be cleansed of "the slag that sensation-hungry modernists and machine-romanticists have deposited on it." Modernism should rather be a desire for a social urban and housing development.

Although both Bauer and Boysen in the post-war period experienced that modernism in many cases was confused with architectural style (such as Le Corbusier and "the international style"), they also saw that social issues were increasingly prioritized in urban politics – at least in Europe.

Boysen was central in the development of the post-war non-commercial housing sector in Norway, which destroyed the cramped living conditions many experienced before and immediately after the war.

The eternal housing issue

When Kåre Willoch and the Conservatives came to power in the 1980s, an extensive process of neoliberalization began, in which the social housing market Boysen and other modernists in particular had worked their way through. Several moved backwards towards the 1800th century, with housing people with access to inheritance or high income gained access to – where the wallet determines where and how you live in Norwegian cities.

Modernism should be a desire for a social urban and housing development.

Here, the mantra is «supply-demand», where more as well as smaller apartments are built with high profit rates. But the new homes are not price regulated. Others, on the other hand, demand that housing be a welfare benefit and not an object of speculation – but not even the Labor Party has this conclusion.

A new social housing sector has thus been developed earlier. If this is to be done again, Bauer must reject vague and ineffective reforms, but fundamentally challenge the socio-economic housing paradigm neoliberalism is selling us.

Here, for example, the current proposed "rent-to-own" model – where tenancy is gradually transformed into ownership – is not enough. The scheme immediately helps someone into the ordinary owner market – similar to housing savings for young people (BSU) – but does not lower housing prices in the long run. On the contrary. Not only the commercial OBOS, but also the municipality of Oslo, led by the Labor Party, has advocated rent-to-own as part of its "third housing sector" – a sector Oslo will disappointingly travel without subsidies. A drop of pink reformism?

It is interesting to see how the pursuit of maintaining the commercial ownership line stands in the way of the rebuilding of a sosial housing policy. Bauer criticized private home ownership in the United States and called for "group initiatives" rather than "individual initiatives": "If only a fraction of the enormous energy that was once directed toward individualistic home ownership was now organized to demand a realistic program for modern construction. […] Then we would really have an American housing movement. "

A good place to start in today's Norway is to demand that we in a modernist way start thinking holistically again by forcing state or municipal enterprises such as Hav Eiendom and Bane Nor to stop treating their plots as objects of speculation and instead dedicate the areas to non- commercial housing.

A forgotten modernism

From the 1960s onwards, twentieth-century modernism was criticized for being both "state" and "rigid." This is a critique that has come in right- as well as left-wing variants – and which culminated in a blue direction in the 1980s.

The Drabant towns became the target of a struggle for freedom. But as Owen Hatherley shows in his new book Save Metropolis on the history of modernist urban planning in London [see separate book review], you should be in a rather privileged position to be able to criticize the welfare state. Young people today, Hatherley points out, only see social democracy eroding.

Both Bauer and Boysen represent a kind of forgotten modernism. Guttu shows, for example, that Boysen saw himself as a liberal Marxist or anarcho-syndicalist and criticized a stiffened OBOS. For Boysen, the contemporaries should rather "make the housing cooperative a real mass movement, with an inner common life and a clear [organis] organizational consciousness". Bauer fought for exactly the same thing. Can a forgotten social modernism that avoids a dead bureaucracy inspire our time – without losing sight of the whole?