(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

[essay] Global injustice is extreme.

Nevertheless, there is little system debate. I will describe here three mechanisms that help sweep the criticism under the rug:

1. The traditional news media gives us a false and outdated worldview.

2. Fairtrade and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) act as a sleeping pad, and are primarily about meeting our need for protection against the connection between ours and the reality of the poor.

3. The vast majority of the rich north-west live their lives completely without contact with the world's poor, who produce our raw materials and consumables.

Slaves of Denmark-Norway. While Norway is a welfare state with a high standard of living and living, the UN can tell that 30.000 children are dying of hunger and malnutrition every day in the Third World, and that two billion of the world's population live in extreme poverty. How can rich people live in the midst of a sea of poverty without protests in the West? In view of the global situation, it is perfectly timely to ask why the 68.000 that went on the TV campaign this year did not march on the government quarter to demand that the exploitation of the world's poor be placed at the top of the political agenda.

Within sociology, the "addiction model" is used to explain how poverty in the world is related to us in the West. In short, it is a direct connection between conditions in rich and poor countries. We became rich because the others became poor. The Kingdom of Denmark-Norway has also been a part of this story, including holding slaves in the West Indies. According to the theory, historical exploitation is held by equal mechanisms such as foreign debt, customs walls and the fact that poor countries can only engage in commodity cultivation rather than develop modern industry.

Norway's welfare depends on as high oil prices as possible. But since the majority of the world's poor population lives in countries that do not have oil revenues and need to import oil for their markets to function, high oil prices lead to lower availability of essential goods and weaken the economies of these states. But even without oil revenues, much of our consumption is dependent on others remaining in poverty. The prices of the goods in the store are kept down because those who produce them have low incomes. This applies to everything from computer equipment, clothing and electronics to food.

Where's the debate? Although there is often talk of our ethical commitment to help, there is worryingly little debate about our role in exploitation. For only a few people mention that it serves our interest that "the others" remain in poverty.

Following disclosures about unethical conditions at the coffee plantations that Norwegian Friele buys from, Thomas Ergo from Dagbladet asked the question of what the purchasing managers who had protested against Friele should do with all the other unethical products in the range. "We'll have to take it another time," replied Christian Sulheim of the Hakon Group.

Although the purchasing managers had been hard at Friele, it was clear that the debate in a larger perspective was something that one would prefer to avoid. The example also shows that Ergo, by asking the question, operated on the outside of what is expected of the media. It was never followed up further in the case.

Within media coverage, one can distinguish between structural and spot lighting. Spot lighting is about individual episodes (or individual products, as in the example with Friele), often told in a form with villains and heroes. Structural lighting, on the other hand, is about looking at the underlying differences and historical conditions that enable injustice. The first form of journalism gives an immediate satisfaction to the journalist who appears as a kind of sheriff – like Thomas Ergo when he arrests Friele Kaffe. The second form of coverage goes against both the audience and the media owners' expectations of what a news item should be. Structural lighting is dismissed as a form of "olds", as opposed to the expected "news", which should preferably focus on people and recent events.

Unlucky. A grotesque consequence of this way of operating the media is that injustice is effectively naturalized. For example, the media often portrays hunger disasters in poor countries as pure bad news (news). The reality is often quite different: Poor countries are forced to use what could have been food land to grow cheap commodities to Western countries to repay old-world debt (olds).

The media also blur the global exploitation by mainly printing from a national perspective. The processes of globalization present major challenges for journalism, but the journalists have not understood this. The traditional news media gives us an increasingly erroneous and outdated worldview. Journalism is caught up in a national mindset, where local angling seems to be the most important journalistic criterion. Why shouldn't "closeness" also apply to the lives of those in other countries who grow our food and sew our clothes, clothes that we know on a daily basis? The answer to that, of course, is that the truth is unpleasant and in the end can result in us having to pay more for the products we buy.

Global apartheid. Western countries derive more from poor countries than they give back in the form of aid. Norway's status as "best in class" among donor countries therefore gives a hollow tone, all the while knowing that this is a narrative that is drawn more often than the narrative that we actually serve on poor countries.

"Norway is making a solid effort to alleviate distress through our aid and relief grants, and through the voluntary efforts of many," replied Finance Minister Kristin Halvorsen when asked why the high death rates among children in the Third World are not placed at the top of the political agenda.

The example shows how Norway as a "donor country" is an important story to keep the reality of the poor away from our reality. Secretary General of Church Aid, Atle Sommerfeldt, compared in the journal Arr today's Norway with South Africa during apartheid. According to Sommerfeldt, the white South Africans under apartheid are the closest we come to a role model for understanding how in Norway we do not take over our role in global exploitation.

Sommerfeldt particularly highlights charity as an important factor in maintaining the racial regime. Many whites in South Africa made a personal effort for black people they knew. There were social institutions for disabled blacks. Moreover, the servants could get medical help, and their children could inherit the white children's clothing. There were also many whites who openly argued that the system was unfair, but the vast majority remained passive. According to Sommerfeldt, personal charity worked so that the white upper class could maintain its moral and ethical qualities in the midst of injustice.

Consumer powerlessness. The most effective story that takes the brunt of the criticism of our role in world poverty stands for the market. According to Douglas Holt, professor at Oxford, the problem of consumer boycotts is that dissatisfaction, which should have been formulated as a political criticism to be effective, is instead expressed against individual brands and therefore allows the market to adapt. According to Holt, the adaptations rarely become anything other than diversionary maneuvers and promotional campaigns. One clear example is when telecom operator Netcom spends ten times as much money boasting of its charity than they actually give to an aid project.

Criticism about financial matters is even easier to manipulate by letting companies hide their real policy behind bland reports. It has become common practice to create own branding schemes and guidelines to reassure consumers, often under the vignette "Corporate Social Responsibilty". But the ethical guidelines are unfortunately voluntary, and drawn up by the companies themselves. They therefore do not focus on the clothing industry in the West, and never question either the industry's high earnings level or the connection between the conditions imposed on the factories and the workers' conditions.

Holt goes so far as to say that consumer criticism only works as information the market uses to renew itself. His point is that companies are gradually adjusting to criticism by decorating new stories about themselves and their ethics.

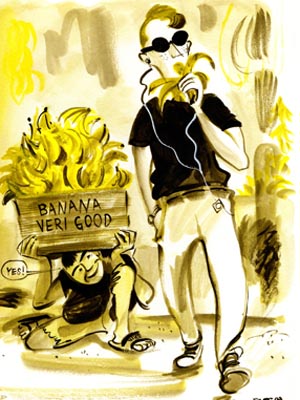

A good example is the marketing of "Bendit" bananas from Bama, which among other things emphasizes ethical production in the countries from which it is imported. The only problem was that on the Dole plantations in Ecuador, workers were earning a salary of around 160 dollars (about 940 dollars) a month, half of what they need to live well. The workers were also unable to organize themselves, and also had a harmful working environment.

When the distance between the campaign and the reality was revealed by NRK Brennpunkt, Bama, who corresponded to full-page ads in the country's largest newspapers, expressed their innocence that this was new to them as well. Bjørn Tore Heyerdahl, project manager at Fairtrade Max Havelaar, subsequently wrote a comment in Dagsavisen supporting Bama that "there is nothing wrong with companies becoming more aware of their corporate social responsibility." We as consumers must recognize and support such efforts. " But what if Fairtrade and CSR do not go deeper than it does in the examples of Bama and Netcom, Heyerdahl? Then the measures are first and foremost about meeting our need for protection against the connection between ours and the reality of the poor. This is how Fairtrade and CSR act as a sleeping pad.

We protect ourselves. The philosopher Martin Buber distinguishes between relationships that are either close to you or instrumental. I-you demand that you meet the other as an equal human being, as a subject and not an object or object.

Sommerfeldt writes about South Africa that the upper class's distance to the blacks was important in maintaining the illusion of a separate reality. If the others got too close to their everyday lives, the contrast could be a moral problem. Surveys showed that no more than three percent of whites had been in black homes, and attempts were made to organize the black lives out of sight to the greatest possible extent. You could actually live your normal life without paying much attention to how the black proportion of the population actually did.

Norwegian business people traveling to South Africa could therefore tell how wonderful everything was, while in reality the black part of the population had living conditions below the African average.

Transferred to today: People from Norway have little contact with the reality of others. You travel to Thailand in a bubble and think that most people work and are good in the service industry. You do not go on charter holidays to look at factories where people are forced to work 14-hour shifts. And if you can't see "the others," it's hard to come close to an I-you relationship as Buber describes.

At the same time, we have greater access to information about the state of the world today than ever before. The media continually displays images of the reality of the poor, and there are plenty of documentaries and writers like John Pilger and Naomi Klein who live by showing the misery. The philosopher Slavoj Zizek's explanation of the West's "enlightened cynicism" makes some sense, but cannot be seen independently of the protective mechanisms offered by voluntary, aid and charitable organizations. As well as the media's meticulous spot coverage, which effectively naturalizes disasters that really follow logically from a global exchange ratio. Paradoxically, charity and media images in this way help to exclude the poor from our moral universe, because these mechanisms free us from seeing our real responsibility: the intertwining of our economic conditions (down to the price of groceries) and those of others places in the world.

The philosopher Thomas Pogge has made one of the most important contributions to global justice in recent years. He believes the crucial step to eradicating poverty is that we not only fulfill the positive duty of "helping" when it costs little for ourselves. On the contrary, his point is that we have violated our even stronger negative obligation to "not hurt". We do this by avoiding dismantling a global institutional order that predictably and inevitably deprives large sections of the world's population of basic socio-economic rights, according to UN living conditions calculations. Real deletion of foreign debt is an important step in the right direction, but this must be driven further by uncompromising activists. In addition, the media must open to structural illumination that more closely brings the reality of the poor with our reality. ■

A version of this article is also in the journal Demo, which is being released these days.