(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

When I was very young, I worked with a slightly older young woman who was a girlfriend with celebrity Frederik Fetterlein. She said. It was in the middle of the 1990 when Fetterlein's "focus" was being "directed away from the tennis career and towards the nightlife", as it is formulated on Wikipedia. Thanks to a third colleague's careful reading of gossip magazines that mapped Fetterlein's journey, we slowly realized that the incredible story of the love affair was pure spin.

Faced with her "lie", our colleague was deeply shaken and insisted that she was Fetterlein's chosen. She went home crying from work, and it all felt completely wrong without me realizing what was at stake.

We were foolish teenagers who knew no better than to perceive her as "a liar" and to be offended that she had taken our ass. But her fierce reaction to being confronted with a different version of reality than she had presented made me doubt. Not if she was really a boyfriend with the world famous tennis player aka playboy. But if lusts were now also quite comprehensive. And if at all it was okay just to throw another reality in her head.

Mediated delusions

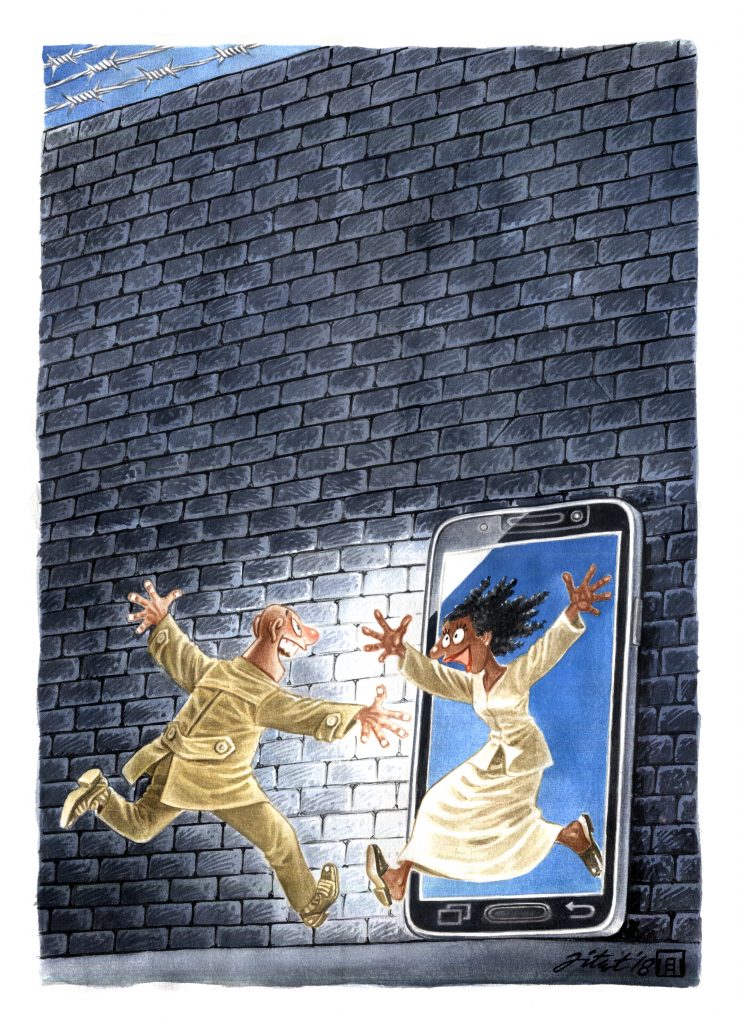

After reading the The Technical Delusion. Electronics, Power, Insanity I have found that the condition of my former colleague may have been rather manifest delusions of reference: "For the psychotic, the media's celebrated ability to simulate 7intimate relationships with complete strangers has dramatically expanded the potential reference sphere," writes media and cultural historian Jeffrey Sconce. "Celebrity stalkers, for example, often hybridize reference delusions to 'erotomania', the very picturesque concept of psychiatry for those who think they are in a romantic relationship with people they don't know or have never met."

While I was reading The Technical Delusion, on the whole, it dawned on me how many experiences I have with variations on "technological delusions". At that time my grandmother – under the influence of powerful pain medication – was convinced that she had seen my mother in The Muppet Show the day before, and with an agreed smile, my mother's astonished refusal expressed expression of modesty.

Or when one of the women at a night hostel I was working on reacted very negatively to the new computers that had arrived for free use. In a confidential moment, she whispered something about being monitored from the internet. And Muslims. Maybe in some sort of conspiracy, it wasn't quite clear.

Where reality begins and ends

But what does The Technical Delusion to a true page-turner, Sconce's fine-grained review of the topography of delusions and their intimate connection to the map we all navigate and which few of us can avoid getting lost in. Some of us do so little, once in a while, and others of us so fatal that we fall beyond the end of the world that we had otherwise learned does not exist.

Sconce elegantly guides the reader through hundreds of years of technological delusions – from the invention of electricity to today's ubiquitous gadgets – with well-told examples from both psychiatry and popular culture (for example, the dramatic real story behind REM's 1990 hit "What's the Frequency, Kenneth »).

Terrorist bomber Timothy McVeigh could come up with the not unlikely allegation that the military had a microchip in his balloon to track and monitor him.

The number of delusions involving technology and media has risen steadily over the past century, and many doctors believe that technological delusions today represent the most widespread symptom among people diagnosed as psychotic. The nerve-wracking of the narrative is that although "delusions are the epitome of the unreal and the irrational, their manifestations and their judgments are deeply rooted in material, social processes," as Sconce puts it.

The voices in my head

Once upon a time, telepathy was something that many highly respected people took deeply seriously and worked on scientifically, Sconce recalls, and his book is – by no means insane – an empathetic introduction to the often invisible zones between psychosis and reality, which Both psychiatry and lay people have the habit of abrogating themselves to overly confident judgments.

When my grandmother had been living in a nursing home for a year, the staff told her she had started hearing voices. It was probably due to fluid shortages, they explained soothingly. So every time she complained about the voices, they gave her a big glass of juice. A few days later I came to visit, and had barely entered the door before saying, "Now they are back! In my ear! "

I walked over to the armchair and bent down so that my ear was right next to hers. And, quite right, somebody fucked up in there. It turned out that a caregiver had turned on the telecoil function, so every time the neighbor turned on the TV, it was transmitted directly into my grandmother's hearing aid.

Fortunately, that story ended untrammeled, but the number of people who experience transmitting (often fictitious) TV voices into their heads without a telephone loop or who experience their own thoughts being transmitted directly to the public is alarmingly high. Sconce writes that a survey among broadcasters in the United States found that nearly half had received letters, calls or emails from people asking them to "stop sending voices into their heads or stop talking about them at tV. "

Psychosis and speculation

Given that technological delusions have become perhaps the most prevalent form of psychosis of psychosis, psychiatry is astonishingly disinterested in describing the concrete delusions of concrete delusions and rather adheres to generic assessments of individual delusions, Sconce argues:

"In a world where terrorist bomber Timothy McVeigh could make the unlikely claim that the military had implanted a microchip in his bale to track and monitor him, psychiatry's language to assess technological delusions has evolved very little since Tausk's era of crunch , x-rays and batteries, ”writes Sconce – referring to Freud's apprentice, who in psychiatry history is described as the first to understand the importance of technology's entry into the development of psychotic thoughts.

When do speculations, beliefs and beliefs about technology become so pathological that medical authorities will have to step in, Sconce asks, adding a question that is at once far-reaching politically and practically crucial: Who can determine what are plausible theories about the invading power of technology, and what are sickening delusions?

Yes, drink your juice now, Mrs. Andersen.