(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

There were strong and justified reactions when Henry Kissinger recently visited Oslo and the Nobel Institute in connection with the award of the Nobel Peace Prize. This invitation – and not least that he himself was awarded this award in 1973 – does not appear any less absurd or reprehensible by watching Adam Curtis' new film, in which the former security adviser and the foreign minister is identified as the root of real evil.

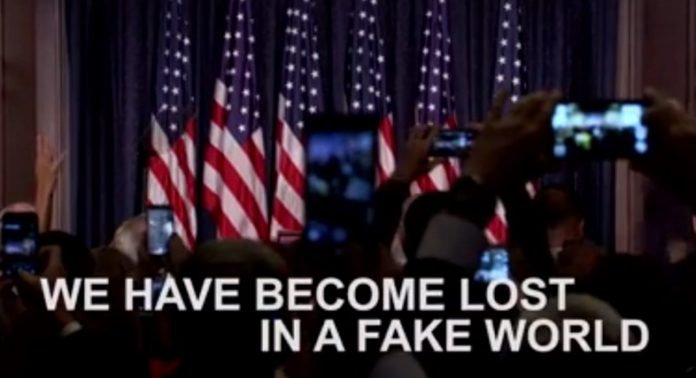

Two cities. Based on the two cities New York and Damascus in the middle of the 1970 century, Curtis sets out to tell a story about the time and condition we live in, and what led up to this. The story deals with the crises in the Middle East as well as in the financial sector, and addresses the emergence of both individualism, suicide bombers, cyberspace, Putin and Trump, to say something about how the false and the false have become normal. Or hypernormal, as Curtis likes to call it, with a term he borrows from Alexei Yurchak's book Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation, about life in the Soviet Union in the last two decades before the system collapsed.

The documentary HyperNormalization is in several ways a description of a postmodern state, in which the great ideologies known to have passed away at death. In line with this, Curtis argues that the belief that one can govern society according to political ideas was first replaced by a cynical realpolitik (for which Kissinger was one of the foremost representatives), and then by a political climate where truth in itself is no longer relevant – neither for the governing nor the governing.

On the contrary, everyone knows that the government's portrayals of reality are not right, if one is to believe the British filmmaker. Such a case must have been in the Soviet Union, where everyone (again with reference to Yurchak's previously mentioned book) pretended to live in a well-functioning society, knowing full well the opposite.

Curtis does not, of course, think that our system is particularly similar to the old Soviet Union, but that we have a similar view that the leaders of society do not know how to deal with the challenges of, for example, the economy. We know they have no clue, and they know we know. But we accept this as normal, because we no longer know of any alternative.

Post truth. For the governing authorities, there is also no point in people believing what they say, says Curtis. Kissinger, in his day, wanted a "constructive ambiguity" as he pursued his divide-and-rule policy towards the Arab countries of the Middle East. A policy Curtis blames for Syria's fierce opposition to the West, which via Iran and Hezbollah led to the spread of suicide bombers, also called "the poor man's nuclear bomb". Reagan and his administration, however, felt that the conflicts in this region were in excess of complexity, and instead presented a simpler "narrative" in which Libya's leader Muammar al-Gaddafi willingly took on the role of the entire insane super villain of the globe.

But especially Russia under Putin (and his adviser Vladislav Surkov) should have introduced a policy – or perhaps a political theater – intended to create a feeling of powerlessness and confusion among people, without even pretending to present any kind of truth. Here, too, Curtis draws a parallel to the United States, and the future president's lack of need to root his statements and attitudes in fact.

In other words, it is as much about "post-truth" as about postmodernism, in a line of argumentation that cannot easily be summarized in a comprehensible way within the length limitation of this article. Curtis' film also lasts for 2 hours and 46 minutes, most of the time with the filmmaker's own layouts on the soundtrack. And it's not always easy to hang with when he explains it either, although the film is undeniably captivating and fascinating.

If Adam Curtis is to be believed, few care whether the preferred story reflects an actual reality.

Video essay. Adam Curtis, who has been called both leftist and neoconservative, taught politics at Oxford where he also began a doctorate, before leaving academia to make documentaries for the BBC in the 1980s. His films have a distinctive style in which he mainly uses archival material – primarily from the British broadcaster he works for, but also clips from feature films and other recordings that illustrate the points. They are also interspersed with one and another interview Curtis has done himself, often worked to look older, to better fit into the whole. But basically it's Curtis himself who tells how things are connected in voice-over, with room for many associations and jumps, and that makes his films a kind of subjective video essays.

Self-imposed authority. Like Curtis' previous film is distributed HyperNormalization only via the BBC streaming service iPlayer, which is limited to users in the United Kingdom. However, at the time of writing, it is also available on YouTube, albeit possibly without the producer's or filmmaker's permission. Either way, the online platforms feel right for the movie, which with its many collages and "remix" -like use of archive clips is close to YouTube's own expression. In addition, it is tempting to point out that the generalizing and partly conspiratorial qualities of Curtis' presentation also give it a certain anchor to the web, despite the fact that he obviously has more academic weight than the usual conspiracy theorists out there.

Nor does one escape from another and (even) more ironic synthesis between form and content in this documentary, where the filmmaker with great and self-imposed authority puts out how different power-holders present simplified and not necessarily true stories, preferably to create an illusion of stability and order. It is easy to criticize Curtis for doing the exact same thing himself, as the entire film is based on his claims and conclusions, without his particular interest in documenting them with anything other than anecdotal video clips. This irony – or perhaps rather the contradiction – is not to be taken lightly by initially stating that the film «will tell the story of how we got to this strange place» – a phrase that makes the subjective storytelling aspect visible, but which at the same time seems to emphasize the truthfulness of the story.

One of the mantras of postmodernism has been that the great stories are dead. Nevertheless, "storytelling" has become a buzzword, often associated with identity and how one wishes to appear. Here, I particularly aim at how communication advisers nauseatingly focus on "what story you want to tell", whether you are a private company, a charity or immigration and integration minister. And if Adam Curtis is to be believed, few in our hypernormal state care whether the preferred story reflects an actual reality.

It is undeniably a mesmerizing message, not to say an unpleasant truth – which in its ultimate consequence becomes a kind of catch 22. Because if he is right, one might wonder why we should react differently to Curtis' story.

Huser is a regular film critic in Ny Tid.

alekshuser@ Gmail.com