(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

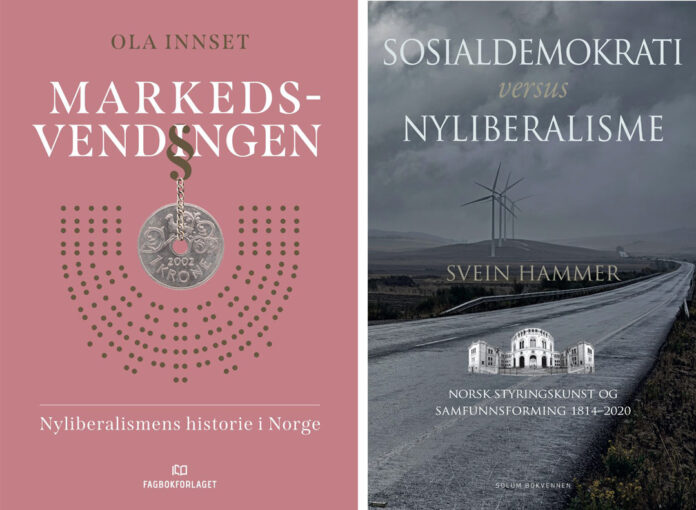

In December 2017 granted Fritt ord scholarship for two projects with many similarities. My first thought was, "Maybe they should be united into one book?" Now, however, there were two books, both published this fall. One is written by Ola Innset, and has been given the title The market turnaround. The history of neoliberalism in Norway. The other is written by me and is called Social democracy versus neoliberalism. Norwegian governing art and social formation 1814–2020.

Each of us has tried to say something wise about how Norway has changed from a social democratic to a neoliberal order. Where Innset is a historian with an emphasis on economic policy, I am a sociologist with an interest in a broader formation of society and people. Our eyes occasionally sweep in different directions, but no more than we often touch the same landscape.

We both criticize the notion that neoliberals want to release market forces completely free, and that they reduce man to a selfish, calculating being. This is a caricature, write both Innset and I. Instead, we see neoliberalism as a conscious project that shapes reality, rooted in the will to give market thinking and competitive mechanisms greater place in society. Many similarities, in other words, but also significant differences.

Two books with a common field of view

Ola Inset's book is divided into «Prehistory (1935–1967)», «The cover (1968–1980)» and «Reform (1981–2007)». Such step by step indicates that we are facing a historian who wants to tell what has happened, which actors and events have been important, how different actors have presented their arguments – and what ideas it has all been rooted in.

Neoliberalism is understood here as ideology, that is, a coherent set of ideas that form the basis of political action. This set of ideas is illuminated and clarified. At the same time, Inset acknowledges that history has not developed as consistently and unambiguously, as the concept of ideology suggests – and adds that neoliberalism can also be understood analytical, where economic policy has changed from the 1970s onwards. A development that has taken shape via various incidents, problems and proposed solutions – but there is still reason to say that the changes have had a neoliberal character.

My book is also divided into three parts. The history of the art of management forms a framework that I use to present «the social democratic Norway» and «the neoliberal Norway». The lines are drawn all the way back to old Eastern ideas about the power of the shepherd, and from there onwards from Jesus and the Catholic Church's intricate apparatus for leading people, to the birth of modern governing art. This opens up for other nuances than Inset's book.

We both criticize the notion that neoliberals will release market forces completely free.

In the book, the actors are toned down, I illuminate discourses rather than ideologies. A discourse is not defined as a fixed package of ideas, but rather as a moving flow that can arise through completely different ideas, concepts and ways of speaking temporarily interacting with each other. This makes it easier to understand the dynamic, complex reality in which both social democracy and neoliberalism are part.

Innset and I walk along many of the same paths, but I try to interpret how the two discourses for social formation work – via selected cases, with special emphasis on housing policy, environmental policy and knowledge policy.

An economic world?

Had it been possible to unite these two book projects? Ola Inset's most important contribution would then be that he goes closer to the actors, their ideas and intentions than I do. Concrete factors of importance for the neoliberal turn of economic policy are elucidated in detail.

He discusses the structure of the economics subject, what kind of professional filter the professionals wanted to produce knowledge through, and what goals they wanted to measure the economic development against. Along the way, we meet the Bretton Woods system and the OECD, Mont pelerin society, Chicago economists and winners of Sveriges Riksbank's prize in economic science in memory of Alfred Nobel as well as theoretical ideas related to monetarism, supply-side economics and Public Choice theory.

Through this package of schemes, actors and theories, Innset establishes a backdrop for the movements that arose with the international economic crisis in the 1970s. Acute problems stimulated professionals to search for solutions adapted to a changing world. As Innset writes, there was a lot of groping in unknown landscapes, but the result was largely a turn in the direction of giving increased power to market processes – which were then brought forward through the 1980s and 1990s. It was not a straightforward process, but it had its consequences.

The factors Innset concentrates on open up for professional discussion: "The modern world is an economic world", he writes. My response is that he has too strong a will to embrace everything within the concept of economics. If we look at the development of national communities in the 1800th century, as well as globalization in recent times, much can be embraced via an economic filter – but we should not take this so far that politics, law, technology and society disappear into an economic conceptual apparatus?

Another topic Inset emphasizes more than me is democratization. His argument is that only when the labor movement won government power could the social economy be shaped democratically and with anchoring in the will of the majority of the people. His somewhat rhetorical point here seems to rest on a tacit premise that state power constitutes a pure tool for democracy, with the effect that a total opposition is established between the democratic state and market power. But it is hardly that simple, one sees this with roots in the French thinker Michel Foucault's analysis of the modern art of government and its varied power techniques.

Social democracy and neoliberalism

My most important addition lies in the use of the term "governmentality". This is actually a pun, which in both French and English weaves the two words "control" and "mentality" into each other. Through the pun, we become aware of how specific management techniques (for example planning instruments, tender schemes, performance measurements) are part of a mutual interaction with our thoughts and ideas about how a society is formed. At the same time, the concept of «governmentality» embraces something more, namely how modern societal development is shaped in the meeting point between the authorities 'management ambitions and various actors' management of themselves.

For example, national neoliberal measures to increase the share of electric cars will only succeed to the extent that people adjust their own consumption patterns.

Inset's utterance of "democratic, political governance" can appear as an idyllicization of state power.

Social democracy and neoliberalism shape both societies and people along their respective tracks. For example, I highlight how social democratic social formation has accommodated a clear "paternalistic" impact, a strong will to intervene and shape us all – from national welfare systems to how people furnished and used their house. It was a strong will to power that unfolded here, which legitimized itself through being democratic and serving the cause of good.

In light of this, Inset's presentation of "democratic, political governance" may appear to be an idyllicization of state power. I think my author colleague would have benefited from an in-depth study of the aforementioned Foucault analysis. Both Foucault's 1979 lectures on neoliberalism and the 1978 lectures on the changing path of governing art to classical liberalism.

Tender schemes and performance measurements

The insight suggests, for example, that the neoliberals' rejection of a rational, planned social development implies a break with the progressive, liberal ideals of the Enlightenment about man-made progress. But according to Foucault, a rejection of total rationality, overview and planning is the very beginning of the liberal art of government – as this allows for indirect government – at a distance and away. In today's neoliberal world, we encounter this in the form of, for example, tender schemes or performance measurements with the awarding of good results. Through such management techniques, the authorities lead us all into a «competition order», where the actors' own assessments and profit-maximizing choices are expected to shape societal development.

This is how a web of state and market is developed. The state forms the space within which the market mechanisms operate, at the same time as these mechanisms represent a continuous impulse to change the way the state functions. Rather than simple divisions between state and market, democracy and capitalism, one must enter into the analysis of governmentality to understand how neoliberalism is also a complex "management technology".

The insight concentrates most on economic policy. But we are facing two societal shaping projects: The ambitions of social democracy have embraced man in all its facets. The neoliberal management techniques, in turn, spread the competition mechanism into every nook and cranny of society – the effect is that more and more situations (whether we are in the housing, environment, school, kindergarten or health field) are embraced by the logic of calculation.

Is the conclusion here that Innset and I should have written a joint book?

State power and governance techniques

Is the conclusion here that Innset and I should have written a joint book? We could probably do that, but at the same time it is clear that we not only look at slightly different things, but also that our respective eyes are differently calibrated.

The insight is oriented towards ideas, actors and concrete processes and, through its appreciation of political governance, suggests a strong belief in (democratic) state power. I am more oriented towards discourses, governance techniques and projects for societal formation – and have a liberal, perhaps a little anarchist impulse in me which means that I do not give myself completely to the talk of political governance.

Our two books contain an appropriate distribution of meeting points and differences and should therefore be well suited for further discussion about how our current reality should be understood.