(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

In every human being's chest there is inserted a principle which we call 'love of liberty'; it does not tolerate oppression, and it yearns for fulfillment. "

With these words about the longing for freedom, the poet Phillis Wheatley (1753–1784) introduced a universal human rights thinking to the North American colonies. The quote above is taken from her article in the Connecticut Gazette in March 1774. In the same text, she advocates for blacks' "natural rights", since "civil and religious freedom are so inseparably united that one gives little or no joy without the other" .

Wheatley had a certain background for launching such radical and universal ideas. She herself felt the unjust world order that prevailed: Due to her skin color, Wheatley had been kidnapped as an eight-year-old from her mother and father in today's Senegal-Gambia region of West Africa. Then she was forcibly sent across the ocean – before being sold as a slave to a white family in Boston.

Wheatley, on the other hand, developed an English writing art so dazzling that she could already as a 20-year-old go to London and get published Poems and Various Subjects: Religious and Moral (1773). This was the third collection of poems published by a woman from today's USA. When Wheatley returned, she was released. As a 22-year-old, in the fall of 1775, she sent a specially written poem to the future president, European-American George Washington. He thanked her warmly for the poem – in a letter in which he mentions her "great poetic talent" and her genius ("this new instance of your genius").

Wheatley was in practice the United States' first "court poet."

Washington passed on Wheatley's poetry, and in April 1776, three months before the United States Declaration of Independence, Enlightenment thinker Thomas Paines published her tribute poem in Pennsylvania Magazine. Paine stated that the poem was written by "the famous Phillis Wheatley, the African poetess, and presented to his excellent General Washington." In practice, Wheatley was the United States' first "court poet".

The parallel is so striking to what happened 245 years later, aptly enough in Washington DC itself, in January 2021. That is when the poet Amanda Gorman (22 years old, like Wheatley) performed her now legendary poem «The Hill We Climb» at the inauguration of President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris. Wheatley is then also among the authors that Gorman says she is inspired by.

African-American thinkers

It is at all striking to what extent the intellectual development of the United States, and thus much of the modern world, has been shaped by the experiences and contributions of the African-American people. And then often in contrast to the abuses and neglect of their European-American citizens.

In Wheatley's time, those with an African background made up over 21 percent of the United States' population – excluding those with an indigenous background. Today, the proportion of African-Americans has halved, due to the enormous immigration of white Europeans in the 1800th and 1900th centuries. Despite the African-American minority, we see time and time again how crucial they have been in developing America's modern history of ideas. This is not least evident in this spring's compact anthology African American Political Thought. A Collected History (Chicago University Press), edited by Melvin L. Rogers of Brown University and Jack Turner of Washington University. Here, the 30 most important African-American thinkers present in separate chapters.

The collection begins with the aforementioned Wheatley, before continuing with thinkers such as David Walker (b. 1796), the author of the anti-slavery appeal An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. The author and school founder Harriet Jacobs (b. 1813). The editor and oratorical gifted Fredrik Douglass (b. 1817), who delivered a crucial speech for white feminists during the Seneca Falls Conference in 1848. The feminist Anna Julia Cooper (b. 1858), who took a doctorate in history at the Sorbonne. Grave journalist Ida B. Wells (b. 1862), who documented the lynching and criminalization of blacks after the end of formal slavery. The legendary sociologist WEB Du Bois (b. 1868), with a doctorate from Harvard. And Zora Neale Hurston (b. 1891), the social anthropologist who is known for documenting racial struggle in the early 1900th century.

The collection begins with the aforementioned Wheatley, before continuing with thinkers such as David Walker (b. 1796), the author of the anti-slavery appeal An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. The author and school founder Harriet Jacobs (b. 1813). The editor and oratorical gifted Fredrik Douglass (b. 1817), who delivered a crucial speech for white feminists during the Seneca Falls Conference in 1848. The feminist Anna Julia Cooper (b. 1858), who took a doctorate in history at the Sorbonne. Grave journalist Ida B. Wells (b. 1862), who documented the lynching and criminalization of blacks after the end of formal slavery. The legendary sociologist WEB Du Bois (b. 1868), with a doctorate from Harvard. And Zora Neale Hurston (b. 1891), the social anthropologist who is known for documenting racial struggle in the early 1900th century.

These were some of those born during the 1800th century. Of the central 1900th century births that are given a full review in the book African Political Thought, are such as James Baldwin, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King jr., Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, Angela Y. Davis and Cornell West.

Common to all seems to be the opposition to human hatred and the struggle for human dignity – carried out in different ways against racism and white ideology of superiority. This is the relatively newly developed poison of ideas that destroys the fabric of society for most white people as well. In sum, these pioneers show that time and time again they have taken the lead before in practice they seem to have been "right" in the end: No one is free until everyone is free.

The white, privileged voices have seldom performed as well – especially not if the theory is opposed to practice and seen in the clearer light of historical hindsight. Rogers and Turner point out in the preface to the anthology that these most central African-American thinkers are often referred to as having "exercised a more thorough examination of the consequences of American citizenship than their white contemporaries, that they have been more truthful of the principles of the Declaration of Independence. they have provided a deeper form of understanding of American citizenship than can be found in their colleagues.

Activist Tarana Burke launched the concept of MeToo in 2006.

Part of the reason for the African-American intellectual success may lie in the WEB Du Bois, in the classic Souls of Black People (1903), called "double-consciousness". to look at oneself through the eyes of others. "Oppression and discrimination make it easier to see the world with one eye, not with one eye. One sees both oneself and others with" the eyes of others. "

Women's influence

In fact, the influence of African-American women is greater than the work African American Political Thought gives an impression of. And I'm not just thinking of key names like the activist Tarana Burke, who in 2006 was the one who launched the MeToo concept, which a decade later would go viral globally. Burke used MeToo as an expression after she had not been able to give a proper answer to a 13-year-old girl who had been abused. This is how she wanted to create awareness about sexual abuse and harassment, especially against young, black women from lower economic groups, such as Large Norwegian encyclopedia now so rightly points out in his article on MeToo. It's probably too early to include Burke in the canon. And the same goes for the three African-American women – Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi and Patrisse Cullors – who in 2013 launched the hashtag Black Live Matter to protest the unpunished killings of blacks (see investigation).

But one of the big names I miss in the anthology, and which in 2021 is not too early to include, is a chapter on Sojourner Truth (1797–1883, b. Isabella Baumfree). She has been named one of America's XNUMX Most Important People by Smithsonian Magazine. Truth was born a slave, but managed to fight free before publishing the book The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: a Northern Slave (1850). She is best known, however, for her speech at the Women's Congress in Akron, Ohio in May 1851. The speech is known as "Ain't I a Woman?", In which she declared to the White House, among other things: "You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear of taking too much, because we can not take more than our glass can hold. "

But one of the big names I miss in the anthology, and which in 2021 is not too early to include, is a chapter on Sojourner Truth (1797–1883, b. Isabella Baumfree). She has been named one of America's XNUMX Most Important People by Smithsonian Magazine. Truth was born a slave, but managed to fight free before publishing the book The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: a Northern Slave (1850). She is best known, however, for her speech at the Women's Congress in Akron, Ohio in May 1851. The speech is known as "Ain't I a Woman?", In which she declared to the White House, among other things: "You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear of taking too much, because we can not take more than our glass can hold. "

Both Angela Davis and Audre Lorde seem to me to live up to Truth's thinking and activism – as with Lorde's starting point in lesbian black feminism. It should be said that the reason why Truth was not included in African American Political Thought, was that a contributor did not provide his text.

Discriminated both as colored and as women

But law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw (b. 1959) Rogers and Turner had in any case not intended a chapter on. And then they miss the very central role she has been given in recent years, which only comes to light in the anthology:

With the professional article "Demarginalization the Intersection of Race and Sex" (1989), Crenshaw launched the now widely used term "intersectionality", or "crossroads analysis". She did this to explain how women of color are affected by discrimination both as people of color and as women – at the same time. Not unlike the message of Truth in the 1850s, she who fought for rights by being recognized both as a woman (among white women) and as an equal human being (in society in general).

How does a hierarchical skin color system work on a more structural, institutional and "invisible" level – which in practice ensures white realpolitik and realeconomic power in the United States?

Crenshaw was also instrumental in the development of "Critical Race Theory" (CRT). This was a concept she created by launching the workshop "New Developments in Critical Race Theory", in 1989 – a reaction to Harvard University refusing to hire a new colored academic after law professor Derrick Bell protested against Harvard's unwillingness to do research on how racial thinking characterizes the legal system. CRT thus does not study racism on an individual level. Rather, one looks here at how a hierarchical skin color system works on a more structural, institutional and "invisible" level – something that in practice ensures white realpolitik and realeconomic power in the United States.

"Critical Legal Theory" (CRT) is such an in-depth analytical tool for analyzing systemic racism in society (a more concrete project than Derrick's Critical Legal Studies (CLS) from the 1970s).

Trump and Fox News

Critical race studies, for example, can be useful for understanding how 53 percent of white women, and 57 percent of white men, voted for President Donald J. Trump in 2020. Incredibly, white women's voting increased by six percentage points on Trump compared to 2016. Without a huge effort from African-American voters, and especially from the If women responded with 95 percent Biden support, Trump would still be president.

In practice, a ban on quoting from, and learning from, mainly African-American academics.

It is therefore no wonder that Trump in September 2020 knocked through a presidential order banning state education on structural racism and discrimination – also known as critical race theory (CRT). In practice, this was a ban on quoting from, and learning from, mainly African-American academics. Trump's order is further proof of how necessary Bell's and Crenshaw's critical race theory is. The CRT ban, which this year was quickly overturned by Biden, is a good example of how systemic racism is implemented by the public sector.

How could an anti-intellectual like Trump believe that the research articles on structural racism were a threat to the United States and the world? Yes, from July 2020 he had listened to Fox News presenter Tucker Carlson and his repeated interviews with conservative activist Christopher F. Rufo, who had used the corona pandemic to follow online conversations against racism. In this way, Crenshaw's critical racial studies became a favorite object of hatred for Trump and right-wing radical culture fighters during the 2020 election campaign.

At the same time, The New York Times' "The 1619 Project" about the significance of slavery for the creation of the United States – a project for which the African-American researcher Nikole Hannah-Jones won the Pulitzer Prize for writing the introduction – is also banned. One will thus simply ban information that there is racism – implied by whites. Much like Russia, Hungary and Poland now prosecute those who provide information on homosexuality and LGBTQ +.

Norwegian quasi-intellectual debate

It is also frightening to see how large sections of the Norwegian public have copied this right-wing narrative from the United States – this notion that critical race theory, ie academic knowledge, should be a "societal problem". This year, "critical race theory" has until the beginning of August been mentioned over a hundred times in Norwegian publications (registered in the media archive Retriever) – without precision and in-depth presentation being particularly prominent.

Torkel Brekke claims in Morgenbladet that critical racial theory and anti-racism are "a threat to academic freedom", and a "totalitarian threat".

The first time critical race theory was mentioned on public websites in Norway, appears to be an article from Nina Hjerpset-Østlie in the Human Rights Service (rights.no) in the autumn of 2016.

But it only took off in Norway after the Civita-affiliated researcher Torkel Brekke published the Morgenbladet text «Parts of the anti-racist movement are reminiscent of a religious revival»In July 2020, just over a month after thousands of Norwegians gathered in front of the Storting to protest against human hatred against, and the harassment of, people of color. Brekke claims that critical race theory and anti-racism is "a threat to academic freedom", a "totalitarian threat": "I believe that the research tradition that is the primary intellectual inspiration for today's revival is Critical Race Theory (CRT) […] . »

This is how the narrative from Tucker and Rufo was copied over from Fox News and straight into the Norwegian quasi-intellectual debate. But we have seen similar phenomena for a long time in Europe: the increasingly totalitarian Viktor Orbán in Hungary began his struggle against gender studies several years ago, a study he had removed from the country. In Poland, social anthropology has become a favorite object of hatred, and historians there are no longer allowed to freely research Polish citizens' contributions to the Holocaust – because only German Nazis were behind it.

In Denmark

In May, a variant of this intolerant contempt for knowledge also appeared in Denmark: A clear majority in the Folketing, including the Social Democrats, adopted almost a threat to Danish universities: They must not let go of African-American thinkers and their critical racial theory. In practice, this is how the introduction to the decision can be understood, albeit in coded language: «The Folketing has the expectation that the universities' managements continuously ensure that the self-regulation of scientific practice works. That is, there is no unification, politics is not disguised as science… »

A main point of view from white politicians and academics has long been that black academics "only" pursue "politics disguised as science". Ironically, this decision comes from politicians in a country that has itself supported anti-scientific racial theories for a couple of centuries. And as if today's colonized canon at Danish universities cannot be described as both a national and a political project (speaking of "politics disguised as science").

The next sentence in the Danish parliament's resolution shows who stands for an illiberal attitude and a counterfactual understanding of history: "Universities are originally a distinctive feature of Europe, with roots in the Middle Ages."

But of course that's not the case. "Originally", universities and higher education institutions were more of a hallmark of Arab countries than of European ones in the "Middle Ages". Today's modern European universities are first and foremost this: a modern phenomenon. Medieval monastic studies have little to do with Harvard.

Ironically, in today's media debate, it is relatively powerless students who are portrayed as a "threat". The reason is that they challenge today's educational institutions and want updated syllabi from the 21st century. While those who designate the students for the Threat itself are the powerful politicians and academics who ban or ban textbooks that are not written by those they are "used to" (in practice, white academics).

White power, racism and critical race theory

Another example is that Minister of Education Henrik Asheim (H) in July appointed a new "freedom of expression committee" for academia. In an interview with Aftenposten, the minister justified the committee's establishment by pointing out that students at the Oslo Academy of the Arts (KHiO) last year had criticized what they thought were «racist structures in the curriculum and learning at the school». Instead of praising students for being critical and academically up to date, the minister stated that such anti-racism is to "gag" teachers, that criticism from below is to have "a lot of power": "In these cases, a few students get a lot of power over the employees. ”

Minister of Education Henrik Asheim is not alone in such a delusion.

The Minister is not alone in such a delusion. Just before the summer, I participated in a strange professional conversation, which I have in mind on the page. Some of Scandinavia's foremost social scientists took part in an online interview, and there was a somewhat limited diversity in the assembly, but still: Suddenly, one of the researchers, who took it for granted, stated that the campaign for Black Lives Matter is the same as "identity politics". And no one is protesting. That's when I realize that I have ended up on the wrong planet. Ideas and performances that a few years ago were in the fringes of American discourse, on right-wing TV channels, have become a natural part of the Scandinavian academic environment.

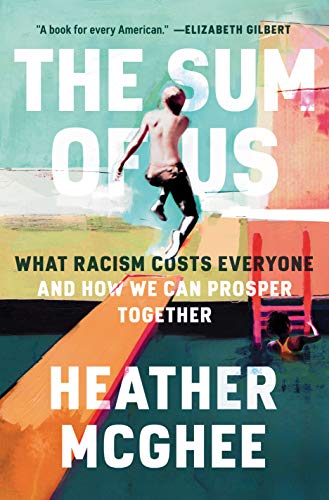

So there is no hope? Can not the dominant academic and intellectual tradition in Norway be reconciled with updated research on white power, racism and critical race theory? Yes, but maybe if we stop looking at history, the curriculum and media access as a "zero-sum game". This is the message in the new book from African-American Heather McGhee, chair of the board of Color of Change, the United States' largest online organization for rights between people of different skin tones. IN The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together (Penguin, 2021) she shows how the idea that blacks 'rights are at the expense of whites' rights is false.

McGhee shows that it is rather in everyone's common interest to understand each other as best as possible – and work for the good of the community. She does not refer to Sojourner Truth's speech in 1851, but she could have done so. So let me rather transfer Wheatley's, Truth's and McGhee's message to Norwegian conditions in 2021:

McGhee shows that it is rather in everyone's common interest to understand each other as best as possible – and work for the good of the community. She does not refer to Sojourner Truth's speech in 1851, but she could have done so. So let me rather transfer Wheatley's, Truth's and McGhee's message to Norwegian conditions in 2021:

There is no threat if students and minorities want to be "woke up", ie beware of the injustice that does not only affect themselves. It's not dangerous if someone wants to read critical race theory, The New York Times, Phillis Wheatley – or to challenge the existing. Rather, it is perhaps the way we best move forward. By listening more. By condemning less.

Or by doing as America's four-star top general Mark Milley. In June, he told a Republican in Congress when the politician threatened to cut support because the Pentagon had critical race theory (CRT) on the West Point curriculum: "What's wrong with understanding, having a certain contextual understanding of the country we are here? to defend? […] Our people should be open-minded. "I myself want to understand 'white rage', and I am white", Milley told US politicians.

Sometimes generals can be more intellectually inclined than academics – and more politically conscious than politicians. The legacy of Phillis Wheatley lives on.