(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

The collection of essays Capitalism and the Camera explores the relationship between photography and capitalist accumulation and exploitation. Editors Kevin Coleman and Daniel James place the emergence of photography between the publication of Adam Smiths The prosperity of nations (1776) and Karl Marx 'and Friedrich Engels The Communist Manifesto (1848) and claims that there is an "inherent link between camera one and capitalism". Cameraone can "enable a critical understanding of capitalist conditions of production" because of its ability to reveal the "constructed aspect" of our social world. GALLERYGraphics can help us recognize "political and economic structures" in our own time and hopefully also give us the opportunity to imagine new structures.

The book consists of a number of essays with different approaches, positions and reflections on the relationship of photography to capitalismn, but I choose to highlight three of the most compelling for the purpose and length of this review:

The looting of the empire

In "Towards the Abolition of Photography's Imperial Rights", author Ariella Aïsha Azoulay claims that "photography was conceptually built up by the plunder of the empire", thus suggesting that the advent of photography is closely intertwined with colonialism.

According to Azoulay, photography was essential to "collect, archive and preserve" the empire's plunder of the colonies, and it joined the imperialist ideology of "documenting and registering from an external position." In this way, photography was not only a registration, it also reproduced the extraction of natural resources and human capital within the territories of the empire.

Before the invention of photography, it was sketches and drawings that met the need to document and record what already existed "before the eyes of the empire". Photography arose out of this need. The photographic apparatus is thus a technology that is both inherently imperialistic and which cannot be decolonized without first abolishing the imperialist practices that pervade our contemporary society and culture.

By placing the photograph in the year 1492 (which, according to Sylvia Wynter, is the year imperialism gains a foothold), Azoulay rejects "the imperialist linear temporality" that separates past, present and future, in order to challenge the histories and theories that reject photography's importance in the colonial project.

A technology that is inherently imperial.

She also argues that an imperialist act exists in the relationship between the documentary/community photographer and the person(s) being photographed, since the photographer gains "ownership of photographs that are generated through an encounter with others", and can reproduce and capitalize on the effects of the imperialist the project, which is the reason the photographs were taken in the first place.

The author defends the view that those photographed should claim rightful ownership of photographs of themselves or their ancestors, as exemplified in the lawsuit against Harvard University and the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology: The plaintiff, Tamara Lanier, requested the rights to the daguerreotype [precursor to the modern photograph, editor's note] of one of his ancestors, Renty Taylor (fig. 1), a man who was kidnapped in Africa and ended up as a slave in the United States. The lawsuit was dismissed, but is proof of how the assets of the colonial powers are protected behind the walls of our cultural institutions.

A despair over the world in general

In "Capitalism without Images", however, TJ Clark puts forward the following hypothesis: What if "the world of images in our current society" begins to "fail to direct our needs and grease the wheels of consumption"? In other words, what if photographs don't convince us to consume? This would involve a "crisis in the image world", but as Clark puts it, capitalism is not only in a permanent crisis, but also thrives precisely in "moments of social proliferation and massive destruction of its own productive forces". This is because under "the ramified social and cultural forms of capitalism" our different ways of life are experienced as an eternal crisis.

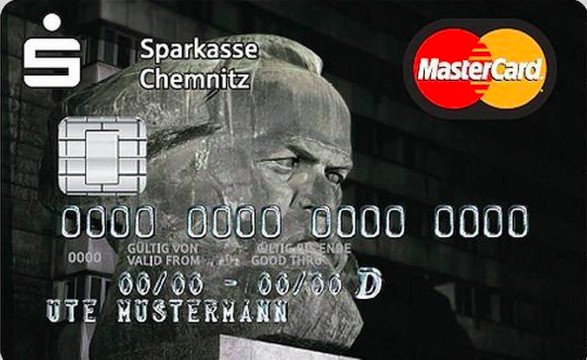

His hypothesis is presented through the examination of an image of a credit card with a picture of Karl Marx (above), from the bank Sparkasse Chemnitz, issued in 2012. Seen in light of the economic recession, this object reveals something about the world we live in, as it literally "puts Karl Marx under the cardholder's thumb", demonstrating that any resistance against capitalism is useless – not only can the resistance be "neutralised", it can also be exploited in the context of consumption.

Those photographed should claim rightful ownership of photographs of themselves.

The argument is in line with my understanding of the moment when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez wore a white dress with "Tax the Rich" in red letters at the Metz gala (see below). The image demonstrates how anti-capitalist expressions are reduced to insignificant gestures and become symbols for social media's immediate consumption. The context, in which the message of the dress was thoroughly disseminated and analyzed, reveals something more than just a dissatisfaction with the "image world", it says something about a "despair of the world in general".

In his conclusion, Clark argues that the riots in London in 2011 after the police shot and killed Mark Duggan were in accordance with the logic of consumption – albeit magnified and parodied – and thus conveyed the dissatisfaction and despair of living in such a "world of images". Whether this dissatisfaction can lead to real resistance, "only time and dystopia will tell", writes Clark.

The production of images

In the epilogue, titled "The Mirror and The Mine: Photography in the Abyss of Labor," Jacob Emery argues that what supports the notion that anyone can take a picture is the belief that photography adds no "labor value" to the world it represents.

However, the "totality of human labor" is implied in the production of images, explains Emery. Considering the now ubiquitous smartphone, Emery argues that "the structure of global capitalism" contributes to the existence of such "photographic devices".

This is because the production of images requires the work of everything from "the camera lens grinder in China, the programmer in the Bay Area, the miner in Africa who procures the minerals, the crews of container ships on every sea" and "the farmers who fed them, and the parents who raised them, and so on ad infinitum until every single worker and all their ancestors are included”.

Here, Emery moves towards what the American Fredric Jameson calls "cognitive mapping" when he gives an overview of the outsourced global work that goes into the production of all images. Emery's epilogue points back to the camera's ability to capture the totality of the capitalist system.

In a similar way, the variety of essays in this collection provides a holistic understanding of "the capitalist image world" and a hope that it can become "readable in its entirety for a viewer also in the future".