(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

What is immoral literature! Harmful literature! Destructive literature!

In my opinion, we live in a worldwide time of crisis, which requires all our awareness, honesty and thinking ability – and the answer comes from this: immoral, harmful, destructive is the literature that puts us to sleep, harmful and dangerous is the literature that works sedative and stupefying. Destructive and destructive is all harmless literature.

We are stupid, lethargic and sleepy enough in advance.

To me, this applies to art or cultural life or the entertainment industry over my head: if these things give a false, romanticized or deceived picture of reality, they are undoubtedly harmful. Examples are escapist "historical" novels, idiotic or not!

To me, this applies to art or cultural life or the entertainment industry over my head: if these things give a false, romanticized or deceived picture of reality, they are undoubtedly harmful. Examples are escapist "historical" novels, idiotic or not!

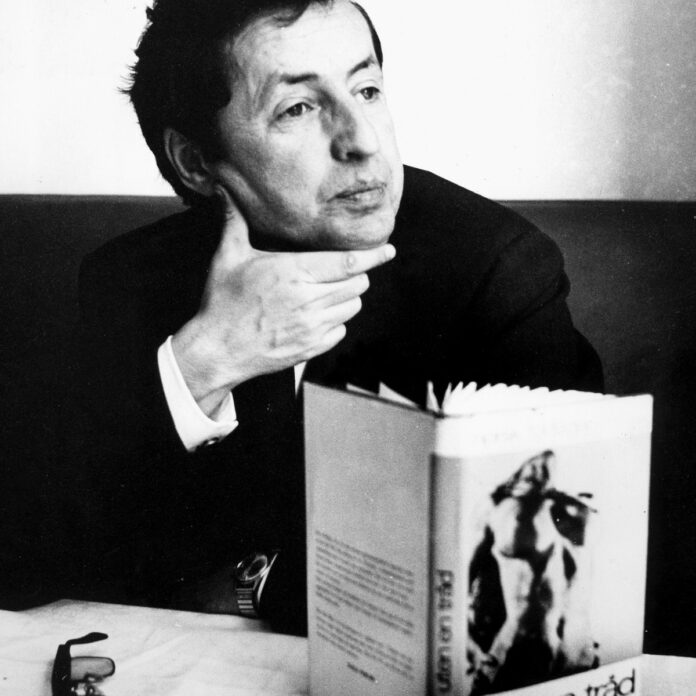

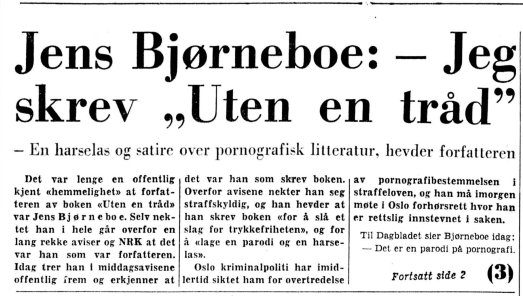

My own perception of the seized "Without a Thread" is, of course, that it is not idiotizing. Otherwise I would not have published it.

I have not a word more to say about the morality of the case. This is my case, and I am not responsible for anything other than my own conscience. If it is affected by the penal code, it does not bother me as a writer.

At one point I will be left in sincere debt to the prosecution; they have seriously asked me a question that no critic would demand a real answer to, namely:

Why did you write the book?

Pretty much depends on the answer, and one is forced to answer it. To be able to answer, I have to ask myself the question: what motives did you really have when you wrote and published the book?

If you look a little deeper at the matter, there is no doubt that this is in fact a grace for a writer; to be taken very seriously, and to be held accountable, forced to account for what he has written and why he wrote it. Of course know I do not.

It is probably extremely rare for one to be aware of one's true motives by an action. Some of them are partly in the light of day, at least apparently; others lie in twilight or completely in the dark. These unconscious motives are probably the strongest and the truly decisive.

Of nearby deliberate and conscious motives, the following immediately appears:

- Economic motives? – Certainly. I always have financial motives – maybe not so strongly while I work, but at least when the book is finished. As long as we live in a society where literature is a commodity, you will have to, whether you like it or not. When it comes to a book that is not idiotic, I must also be allowed to do so. I would like to make money, but that is not my main interest.

However, there is one aspect of the question that has validity far, far beyond my person, and this particular case. There is a tragic aspect, namely: the working conditions of a Norwegian author. Even when he has a relatively well-known name, even when he sells reasonably well, even when he is known outside the borders of this country. These are not purely financial terms, but they are probably financially conditioned.

For my own part, this is not about any radical economic misery; to be a writer I feel good. The case is also more complicated for other colleagues than that.

To be able to carry out a larger, coherent work as a truly artistically ambitious novel or play, one must be able to work long periods in a row, several months, one year, two years. How do you feed yourself and your family during such a period? -

You can only do your best in a situation of profit, rested and with full force. You must be clear in your head, you must have job satisfaction to do good work. As you get older, two things happen; one does not have the same physical strength as before, and the artistic self-criticism and ambition rise. Since I started writing, I have been able to make money from it, enough to make a living. But how have I earned them?

You can only do your best in a situation of profit, rested and with full force. You must be clear in your head, you must have job satisfaction to do good work. As you get older, two things happen; one does not have the same physical strength as before, and the artistic self-criticism and ambition rise. Since I started writing, I have been able to make money from it, enough to make a living. But how have I earned them?

It's been fifteen years since I made my debut. Since then I have written and published fourteen books, the fourteenth coming during the autumn. In addition to these books, I have made a number of translations. In addition to my own books and translations, I have written over a thousand articles for magazines and the daily press, as well as some other things. In sheer amount of material, these articles and essays make up well over twice as many of the books. Even a selection of the best things would make up at least fifteen volumes. I have never had time to edit any essays or collection of articles together. But if I published half of them in book form, in fifteen years I would have written approx. thirty volumes.

I have felt the past fifteen years as a moral and social conscription, I as a writer had no right to evade.

Over the last few years I have translated and published in book form: a book from French, a play with songs from German, a great novel from German. I have published my own novel in German. I have published two of my own plays in Norwegian. I am also publishing a new novel in Norwegian. An earlier novel has been published in a new edition. I have had a theater premiere in Norway and one in Finland. There are four or five premieres in preparation in Norway, Denmark, Sweden and Germany. One of the plays has in a special version been played on tour in four Nordic countries. Together, the two plays have been sold to eight or nine theaters in about a year. In addition to this, I have also written some poems, among others

In total, this has brought in money, but no more than that I have had a working day of twelve to fourteen hours in the last six months, of course without any kind of holidays, Sundays, rest days or holidays. I want to repeat that I am one of the luckier among Norwegian authors.

It goes without saying that hardly any human being can continue such an overproduction or such a work pressure longer than from fifteen to twenty years. Due to time constraints and overtime, some of the books have hardly become what they could have been. Although I think there are two exceptions: the play that will be performed at the National Theater in November, "The Bird Lovers", and the novel that will be published in Gyldendal at about the same time: "The Moment of Freedom". I believe that these two things mean the absolute maximum of what I am able to perform today. (They have then almost all taken my life.) But that the last one was possible at all, is due to help from others, it is due to a government work scholarship, as well as advances from the National Theater, Gyldendal and from Fritz Berg, who is now with me charged with violation of size 1 § 221.

I do not mention this to complain; I have chosen this profession myself, and have to empty the cup to the last drop. I mention it to suggest how Norwegian authors' working conditions turn out, when they are particularly favorable.

In the opinion of the people, all people have the right and duty to think about making money, only writers do not have this right. Basically, it is both poignant and flattering that people have this view: it means that we are considered a select group of people who are committed to uncompromisingly following our conscience and our convictions: our calling.

It is completely indifferent to me, whether Without a Thread has literary value or not; the write-down and even more the publication of the book has in the long run been an artistic one

and morally indispensable necessity.

It is true that you get angry very often when we do it, but you expect it from us and you forgive after a few years. Today I am sure that schoolchildren have forgiven me "Jonas", that those responsible have forgiven me "Under a tougher sky", and I even believe that the police and prisoners have forgiven me The good shepherd og Many happy returns of the day.

But one would not forgive me a "speculation" in something that went against my convictions. Probably right.

This was a long answer to the question of "economic motives": they are certainly present, but not to such an extent that I regret them. It is of course possible that I lie both to myself and others, but in that case, then I lie so I believe it myself: a pious and classic self-deception.

With a certain right, one can say that "Without a Thread" has helped finance the first novel I have published with an artistically good conscience, "The Moment of Freedom". I almost do not care how good or how bad it is – the main thing is that I know that I have done my utmost. If it's obsolete in fifty years, it's a bad book.

What other conscious motives existed during the write-down and publication of Without a thread?

- Satire, harselas, parody? – Yes, probably too. Of course, it is possible that I rationalize them, but I do not think so.

- Political and cultural policy motives? – Definitely, and definitely visible to a not completely unconscious reader.

- Want to say something completely to such an extent that it is actually said once and for all, and done with it? – Yes.

- Need sensation and publicity? Hardly.

One could imagine several conscious motives, but I think they would be irrelevant. On the other hand, partly during the writing of the book, partly after the police seizure, I have become aware of absolutely decisive motives. I actually think I had to write the book, and I think it's an important book in the middle of a turning point in an authorship, and a personal development and maturation phase; in my current situation. It is possible that I have found two determining motives and it is possible that it is one and the same motive, only in different functions.

It is obvious that "Without a Thread" has contributed to the financing of "The Moment of Freedom". But there is another and far deeper connection between the two books: if I had not first written and published "Without a Thread", I would not have been able to overcome the inhibitions against writing The moment of freedom. It may sound completely ridiculous, but when you know the process from the inside, I have done the same thing with both books, only on two different levels: what is done in the sexual area in the first book, is done in the purely mental and artistic in the "moment of freedom", namely to be completely consistent, completely ruthless – and without a single thought of what people would say or mean.

It is embarrassing to be 46 years old, before one has understood that this is the only attitude that entitles a person to write and publish books.

It does not matter to me at all whether Without a thread has literary value or not; the write-down and even more the publication of the book has in the long run been an artistically and morally indispensable necessity.

The second, unconscious (which may be identical with the first) lies in the fact that there is something called å burn their ships.

If you as an artist and human being are to move forward, you must ensure that you have no way back.

I'll have to talk about my other books to explain what I mean. But first an example taken from the myths of a famous French painter: in the hallway outside his studio he had wallpapered the walls with a horrible collection of obscene drawings. He explained that they kept him out of touch and bored people from life, ie spared him from talking to people who met him on the wrong terms. He systematically destroyed his reputation for people who emphasized such things.

Much of what I have previously written has been morally covered and justified, so to speak, morally defended, in that I have incessantly dealt with other people's problems. I have been addicted to finding a moral defense for writing at all; I have thought about what others thought or wanted to think, believe and say.

I have written a number of semi-documentary novels of a socially critical, humanistic content. I have needed a moral pretext to do something as useless as writing. There is a stylistic, a mental and an artistic break in all previous novels, as well as in the first play, Many happy returns of the day!.

I do not regret or apologize for this socially critical or committed line I have followed. On the contrary, I'm glad I did. I have felt the past fifteen years as a moral and social conscription, I as a writer had no right to evade.

But one day you get over conscription age.

And I know that if I am to do any good for myself in the future, then this benefit will consist in me writing the truth that is uncompromisingly my own truth, the one that just me know – because only I am I, and only I can see the world in my way.

It certainly does not mean that I will switch to an ivory tower when I write in the future; both "The Bird Lovers" and "The Moment of Freedom" are political works, but they are in my way.

Of course, one can say that it is strange that a grown man must have external aids to dare to be himself, and to that I can answer that yes, I am so weak. But it was imperative to get rid of me the last remnant of a sympathy from a team that has felt this sympathy on false premises.

What I have left to say is of a kind that can only be expressed through a man who is completely independent of the opinions of others. I owe this to my readers, my children and myself.

There is a very visible bond between the two books. They have a common theme, which is so clear, that no one who read both books would be able to avoid discovering that they were written by the same author. "Without a Thread" was published anonymously, but anonymity had no chance of surviving November 1966 – that is, the publication of "The Moment of Freedom". These are the depictions of the "entertainment district" in St. Pauli, the Reeperbanen in Hamburg; – I did not give Without a thread from me, before I was pretty sure the book was signed this way. I was simply unable to give up.

Thus, the motivation for anonymity – at least for myself – begins to become almost opaque. Although a kind of system you still see: anonymity, the blank title page without author name, seems far more provocative than a normal pseudonym would do. The book calls for seizure, both through the title, through the cover and the lack of author names. This brings a third, unconscious motive into the picture: I must have the desired seizure, the desired indictment and the desired process. In short: I must have wanted exactly the situation that has arisen today.

And why?

Probably for a variety of reasons.

The situation that has arisen is absolutely excellent: it creates a starting point for a civilized and factual debate of principles on whether we should continue to maintain limits on freedom of expression in this country, and on where the boundaries should go. The question today is completely fluid; the most idiotic, pathological and outrageous depictions of blood and violence are allowed, as are picture sheets of an obscenity that can hardly be pursued anymore (eg close-ups in color photographs of the vagina and clitoris) – while books by a deeply serious, great author like Henry Miller is banned. There is a lack of logic, which approaches totally mentally weak. Police officers are set to study the flora, you will find this in order (the magazines are, among other things, regularly advertised in the daily press). Marquis de Sade can be bought fresh and blood-dripping in English, and is thus allowed for those who have a slightly higher education, but forbidden for those who only know Norwegian. Hyper-

pornographic images are allowed for children, serious literature is forbidden for adults.

The authorities' handling of the censorship regulations is completely arbitrary and left to pure chance, and to the discretion of the police.

The aspect becomes eerie, when one has the Emergency Preparedness Acts hanging in the background: when can we be arrested and prosecuted for treacherous opinions or reading of treacherous writings? – Police Constable Hansen decides it together with God knows who, with the detective and the public prosecutor?

Or who in the world is that?

We have the opportunity to take the debate now, and God help us if we do not.

Also read: From the convict's point of view

From our 20-page theme about Jens Bjørneboe in the autumn issue of MODERN TIMES.