(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Alexander Kluge & Gerhard Richter:

Dispatches from Moments of Calm

Seagull Press, 2016

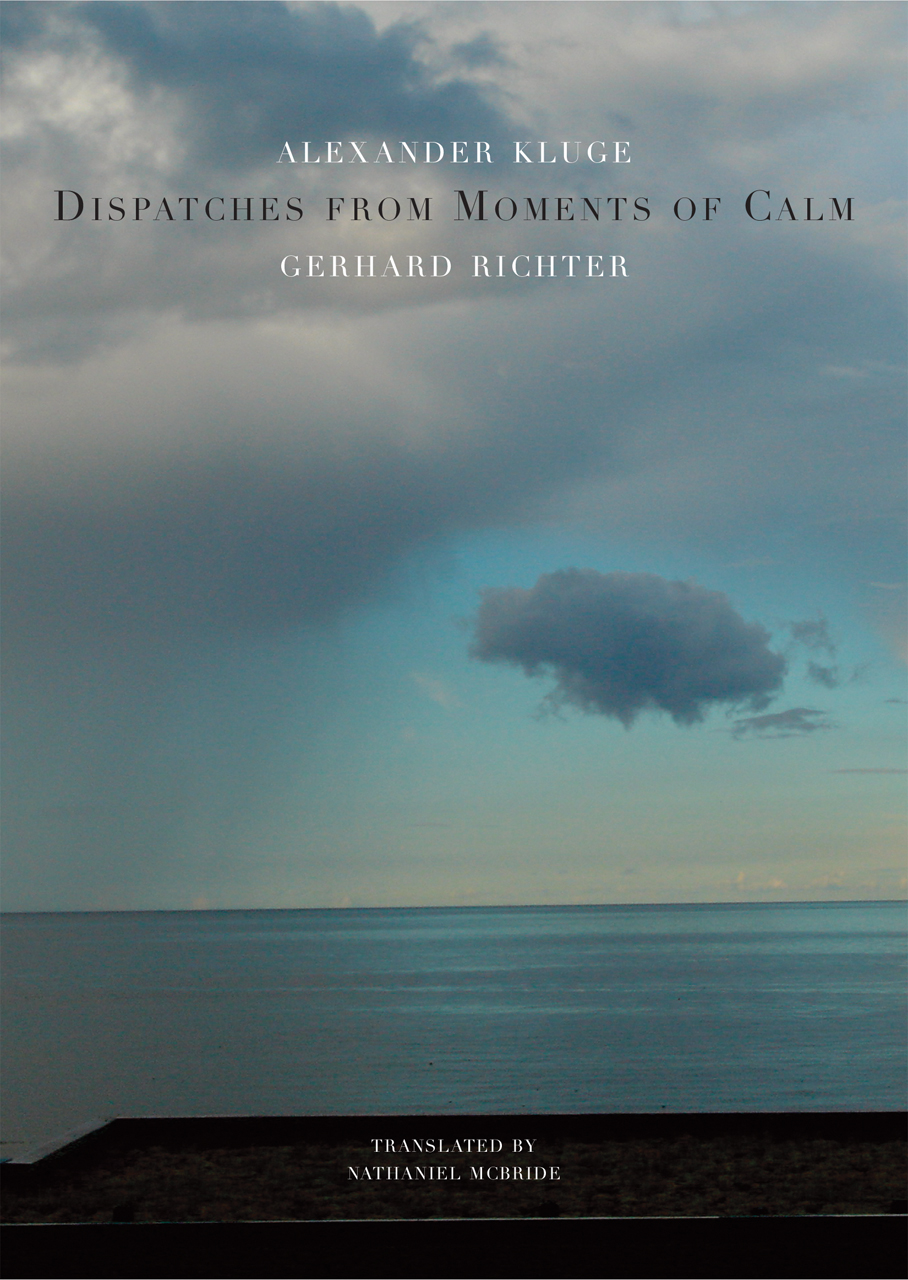

The 5. October 2015 the German newspaper Die Welt published their daily newspaper edition, but everything looked different. Quieter. The current news forgotten just as quickly as they were read was gone, replaced by a unique calm created with the care of contemporary chaos. The calm was created by the painter Gerhard Richter, who had been advised this day to fill the newspaper with his personal statement: Sent letters from quiet moments in troubled times. The pictures privileged the personal and concrete sensory impression that moves from the intimate to the abandoned houses and deserted landscapes. The pictures were like stops, small awareness exercises and fields that turned into a different reality. Even in the most personal way, Richter had come up with something substantial and therefore something general, common. With this printed newspaper on this day, he created a piece of mass art.

The 5. October 2015 the German newspaper Die Welt published their daily newspaper edition, but everything looked different. Quieter. The current news forgotten just as quickly as they were read was gone, replaced by a unique calm created with the care of contemporary chaos. The calm was created by the painter Gerhard Richter, who had been advised this day to fill the newspaper with his personal statement: Sent letters from quiet moments in troubled times. The pictures privileged the personal and concrete sensory impression that moves from the intimate to the abandoned houses and deserted landscapes. The pictures were like stops, small awareness exercises and fields that turned into a different reality. Even in the most personal way, Richter had come up with something substantial and therefore something general, common. With this printed newspaper on this day, he created a piece of mass art.

Blast the present. One of those who paid tribute to this work was the German film director and writer Alexander Kluge, who accompanied by Richter's image, began writing small stories. This book brings together Kluge's 89 small stories with Richter's 64 images. The result is a strange, beautiful and meditative book – but it is also more than that: it is also an attempt to give an idea of what it means to understand the story, something that has always occupied Kluge. The story is not just the linear news story, which often coincides with the history of the elite and the rulers. Sent letters about quiet times pulls the emergency brake in a turbulent time, in the linear time of progress, and brings a contemporary to the day that is bursting between a lived and unlived experience. Richter's pictures made Kluge stop, think, wonder. None of Richter's images are sensational or recognizable, but neither are they abstract. But as invitations to wonder, to be amazed, to get lost, as if this was the most enlightening thing. Like the eye that sees the blue tit using 23 attempts to salvage a biscuit that really looks like it's thinking along the way about every single detail. Like the dog Leica (from the camera) lying in the morning sun, who is probably a dog, but who has nothing in common with the space traveler Laika. Also it lay quietly in the space capsule, trained as it was to withstand stress. It died, as you know, from overheating before the poison pill that was supposed to send it to death worked. Kluge slices that «this noble dog could never be said to lie quietly in his basket in his circle around the earth 18 000 miles per hour. The dog lying there in the morning sun has nothing in common with the dead space traveler, neither fate nor name ».

At «se». In 1946, the Russian astrophysicist Gamov, who in 1946 flew around the United States and Canada to give lectures – and suddenly looks at a noisy café in New York with his own eyes, in one of the few quiet moments he has, rotations of atoms and subatomic particles, their spin, the constant revolution of molecules and particles, the rapid spin of galaxies. He experiences this snapshop as one unified movement as a complex piece of music, which, like something he had heard in Venice's cathedral in the 1930s, which he had been allowed to visit by Stalin. Rudolf Steiner was once asked what he understands by the case, the incident, but avoided the question on which Kluge comes to his rescue: In the summer of 2002, a group of children from the Russian city of Ufa, who had been honored with a trip to Spain on because of their good looks, not their planes that arrived late in Moscow. They all died in the unauthorized flight used for their final destination. But shortly before boarding, two Ufa representatives arrived to take their children off the plane. They refused the children to fly a plane that had not originally been arranged for the trip, and took the two young people disappointed back to Ufa, where they were subsequently received with open arms (the accident had meanwhile taken place). Kluge writes that «in anthroposophical science this is an example of a sense of the case […] They know about these (future events), not because they can trace their cause, but because they can« see »the density which signals a danger» .

The circus tamer of the case. On the whole, this feeling for something in the middle of time, which also has to do with the random and unexpected, is a recurring theme. Kluge quotes Walter Benjamin's statement calling the members of the Bauhaus "the circus dumpsters of the case" because they relentlessly train to master the case so they can also let go, surprised so that something extraordinary can happen. A tension between discipline and being out of control. Opera singer Leonard Warren, known for never saving himself, was to open Verdi's Opera in 1960 La Forza del Destino at the Metropolitan in New York. Warren sings the role of Don Carlos, brother of the unfortunate Leonoras, and he seems to have trouble with his aria. As if for a moment he is breathing a little too deeply, after which he falls forward with his head down on the floor. The decline was only too real, as Kluge noted. There was a hiss through the audience. The singer playing Alvaro shouts, "Lennie, Lennie!" The hands grip the falling one. The blood runs out of the broken nose. Great confusion. One tries word-of-mouth method on the lifeless man, but without success. The play's director steps onto the stage and addresses the audience: “This is one of the saddest moments in the history of the theater. May I ask you to rise up. I'm sure you understand that the play cannot continue. " Only then is the great baritone singer carried off the stage. The critic of the Washington Post wrote that this evening in the theater, which ended at the same time as the opera would have ended, has moved him more than any other opera would be able to. Kluge: "Warren's total dedication – ready to sacrifice his life – had a decisive effect on the person who has so unfairly criticized him."

The book pulls the emergency brake in a turbulent time and brings a contemporary to the day that is bursting between a lived and unlived experience.

Seize the case. During the last exercises for his behavior of Europas 1 & 2 at the Frankfurt Opera House in 1987, John Cage, the man who became famous for his music concerts without music, lived at the Hotel Frankfurter Hof. When he received the news that a fire had broken out in the opera house where his own piece of music was to take place, he took his tape recorder with him and filled his pockets with microphones and hurried off. Firefighters had to wait to put out the fire until the roof fell down. The acoustic power and reverberation of the fierce firestorm, the flames' suction of oxygen from the surrounding air and the falling roof produced a sound Cage had not heard before. For the actual behavior that had been postponed for a few weeks, Cage used the footage from the fire of the opera house along with some previous footage of an airstrike on Beirut. Cage combined this with a number of other explosion recordings and included it in the last act of Bernd Alois Zimmermand's opera The Soldiers, which the members of the orchestra were to play on instrument, but on the basis of their own chosen principle of chance. The finished tape version, unmarked and unprofessionally tied together, was mistaken for rubbish by a hotel assistant and thrown in the bin.

Shortly before his death, a friend of Cage's had to perform a performance using one of Cage's old recordings. Followed by a long telephone conversation with his partner who had acquired a violent flu, Cage wrote Short Concerto for Cough – Deep in Bronchials, Sniffling and Selected Notes by Bach, Schönberg and Myself. The recordings consisted of various coughing noises and not least the irritations caused by a cold. Cage argued that nowhere else is there such a rich variation as air forced out of the abdominal region through the vocal chords and up into the head, all accompanied by a bronchitis tube. For him, these sounds surpass the voices of an opera singer. They have significantly more harmony. After a conversation with his friend Heinz-Klaus Metxger, he gave the play the German title: Rotz und Wasser – «Snot and water».

While the Titanic sinks. During an attack in the Lebanese war, the Eldorado cinema was hit and destroyed by the bombs. The couple who ran the cinema had removed the rubble and erected a tent on the bare ground. Here they set up a projector that they had saved before the cinema collapsed. While people were watching movies, the soundtrack of the movie mingled with the sound of the fights around which alternately approached and disappeared. The "cinema-goers" were safer under the tent than they would have been in a solid building, as another attack on a ruin was seldom carried out. “Guests found this‘ emergency cinema ’encouraging. Here they sat surrounded by their father. It didn't matter what movies were playing as long as the projector was running. "

History postcards. Richter and Kluge's collaboration shows life as something that moves in several directions at the same time. Kluge's texts are not printed below or next to Richter's images, but appear to be random. The reader is left with the impression that other stories could also have been told. The indeterminate nature of the images keeps the imagination open. The current news piles up the information, but makes us more storyless. The book's slow postcard expands the space of the present and brings it into contact with multiple times, making more pastes present.