(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Spain is one of the few countries where anarchism's struggle for freedom and solidarity gained a foothold for a period. At the time of the Spanish civil war in the 1930 century, there were around 11 millions working. Of these, eight million were landless poor laborers, industrial workers, miners and craftsmen. There were one million privileged government officials, clergy, officers, intellectuals and capitalists with larger properties. Between these extremes was a middle class of a few million traders, bureaucrats and business owners.

The privileged and the middle class had long stood for a politically repressive system, and therefore a radicalized working class. These were later further suppressed by the Spanish dictator franc. Fascists from that time have since held important positions up to our time.

As early as around 1860, there were circles among the workers who studied the anarchism and ideas of Pierre Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876) and Catalan federalists such as Francisco Pi y Margall. Some factions were formed that supported the ideas of Bakunin (Bakunism), who, according to Margall, wanted to "abolish capital, state and church rule, and establish anarchy, free federations, and free trade unions in their ruins."

“If anyone until they turn 45-50 years old, works 4-5 hours a day, man will easily produce what is needed to ensure the welfare that is needed. "

Spain achieved with Margall to become a republic in 1873 – for five weeks. The monarchy was reinstated, making it difficult for anarchists to operate for the next decade.

Around 1909 came another "tragic week" in which the anarchists' resistance struggle was bloodily suppressed, with government troops arranging mass arrests, death sentences and executions. In response, syndicalists emerged CNT ("The National Labor Confederation"), the largest trade union in Spain in the 30s.

With the later call in 1931 for a new Spanish republic, one could interestingly see the more pragmatic purpose of the anarchists: organizing from below; control of the means of production and extensive distribution to ensure the poor. Spanish thinker Diego Abad de Santillán expresses just before the Civil War in the book After the Revolution (1936):

"When it comes to a new economic and social system, combating the oppressive forces can only be achieved through conviction and practical experience.... We cannot use violence against those who have opinions and ways of life other than what we propose. Here, our respect for freedom must also be a respect for the freedom of our opponents to live their own lives. "

What was done?

In Catalonia where the CNT labor force dominated, the regional government was declared inoperative, and spontaneous anarcho-syndicalist labor committees were created instead.

Barcelona became the very symbol of the realization of revolutionary or anarchist ideas. A number of measures were implemented: free public transport by bus and subway; a number of directors were appointed; the railway was now collectively run by the unions (CNT / UGT), and the telephone, gas and electricity systems were taken over and far more efficiently run by committees. The same thing happened with the hotel and restaurant business as well as theater and the press. These were not "forced socialized" but run by their employees. Anarchists improvised by creating "folk kitchens" so no one would starve.

"Socialism can only emerge from the spirit of freedom and voluntary entities"

Small businesses were allowed to exist, but larger companies were collectivized. With over 20 employees, workers' unions were created. Business executives and business owners were redefined as "employees" and had to participate if they were to continue in the business. Around 70 per cent of all industry and crafts in Catalonia were socialized and run by wage earners. For example, the textile industry, where over 250 worked in 000 large companies. Or, where 400 per cent of Catalonia's 80 large agricultural holdings, with half a million workers, were allowed to collectively operate. They went away from operating on the basis of profits and abolished stock dividends. The anarchists chose to rationalize productions and merge unprofitable small businesses together. At the same time, wage differences between the companies were allowed.

The basis for the pragmatic-economic anarchism introduced in the 1930s was an attempt to allow the work to be characterized by solidary mutual aid. The economy was organized with mutual credit between companies – in accordance with the ideas of the anarchist Proudhon. Even coffee was free at the coffee houses and haircuts for free at the hairdresser, if you participated in these collective activities. One might ask why one could get free five liters of wine a week, but around 40 poor people received free clothes, medical care and medicine every day.

However, this new society was turned down, since Stalinists, Communists and Conservatives eventually succeeded in reintroducing the monarchy. The anarchists were in a way betrayed by the communists. As is well known, Marxist believers have long had a much greater belief in the importance of the state or party.

The Classics

Let me mention five classic anarchists who can shed light on the history and ideas behind today's CDR and the protests in Catalonia:

by Mikhail Bakunin inspired as mentioned the anarchists of Catalonia. The Catalans today might like to repeat his: "rather from below and up, through free federations." And Bakunin once wrote that "without solidarity, freedom would remain stupid forever ... while without solidarity, freedom would never have existed." He regarded man as "a complete material being" and rejected the phenomenon he saw coming – that Marxism with Lenin and Stalin became an oppressive regime. Already a century before the revolution, he criticized the all-inclusive party with its all-powerful bureaucracy and apparatus of terror.

by Mikhail Bakunin inspired as mentioned the anarchists of Catalonia. The Catalans today might like to repeat his: "rather from below and up, through free federations." And Bakunin once wrote that "without solidarity, freedom would remain stupid forever ... while without solidarity, freedom would never have existed." He regarded man as "a complete material being" and rejected the phenomenon he saw coming – that Marxism with Lenin and Stalin became an oppressive regime. Already a century before the revolution, he criticized the all-inclusive party with its all-powerful bureaucracy and apparatus of terror.

For Bakunin, freedom is first and foremost an individual task, then society comes, but: “Freedom is in no way isolation, but mutual recognition […] only in a society with other people can I see myself as free […] only through all the common tasks of society become man a human being. "

And considering Karl Marx with the main street named after him in Berlin (see mainly), Bakunin also writes: “Marx is an authoritarian and centralist communist […] He strives to introduce economic and social equality through state power, through a very strong and so to say despotic temporary government – that is, through a denial of freedom. "

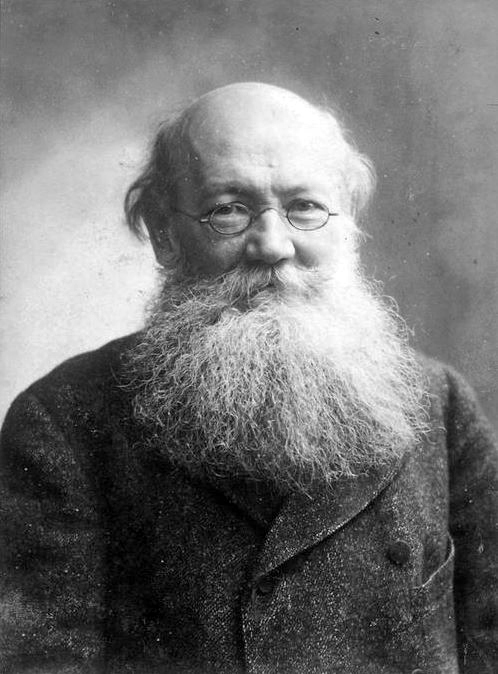

Russian Pjotr Kropotkin (1842-1921) wants the means of production to be the centralized common property. State power must be transferred to free municipalities. He also emphasizes mutual assistance as a moral solidarity foundation. In addition, he believes that technological developments will lead to an abundance of goods and more education for ordinary people, and that automation (mechanization) can reduce the working day for most:

Russian Pjotr Kropotkin (1842-1921) wants the means of production to be the centralized common property. State power must be transferred to free municipalities. He also emphasizes mutual assistance as a moral solidarity foundation. In addition, he believes that technological developments will lead to an abundance of goods and more education for ordinary people, and that automation (mechanization) can reduce the working day for most:

“If anyone until they turn 45-50 years old, works 4-5 hours a day, man will easily produce what is needed to ensure the welfare that is needed. " He recommended that the people take over large private properties – as we saw this happening in Spain in 1936.

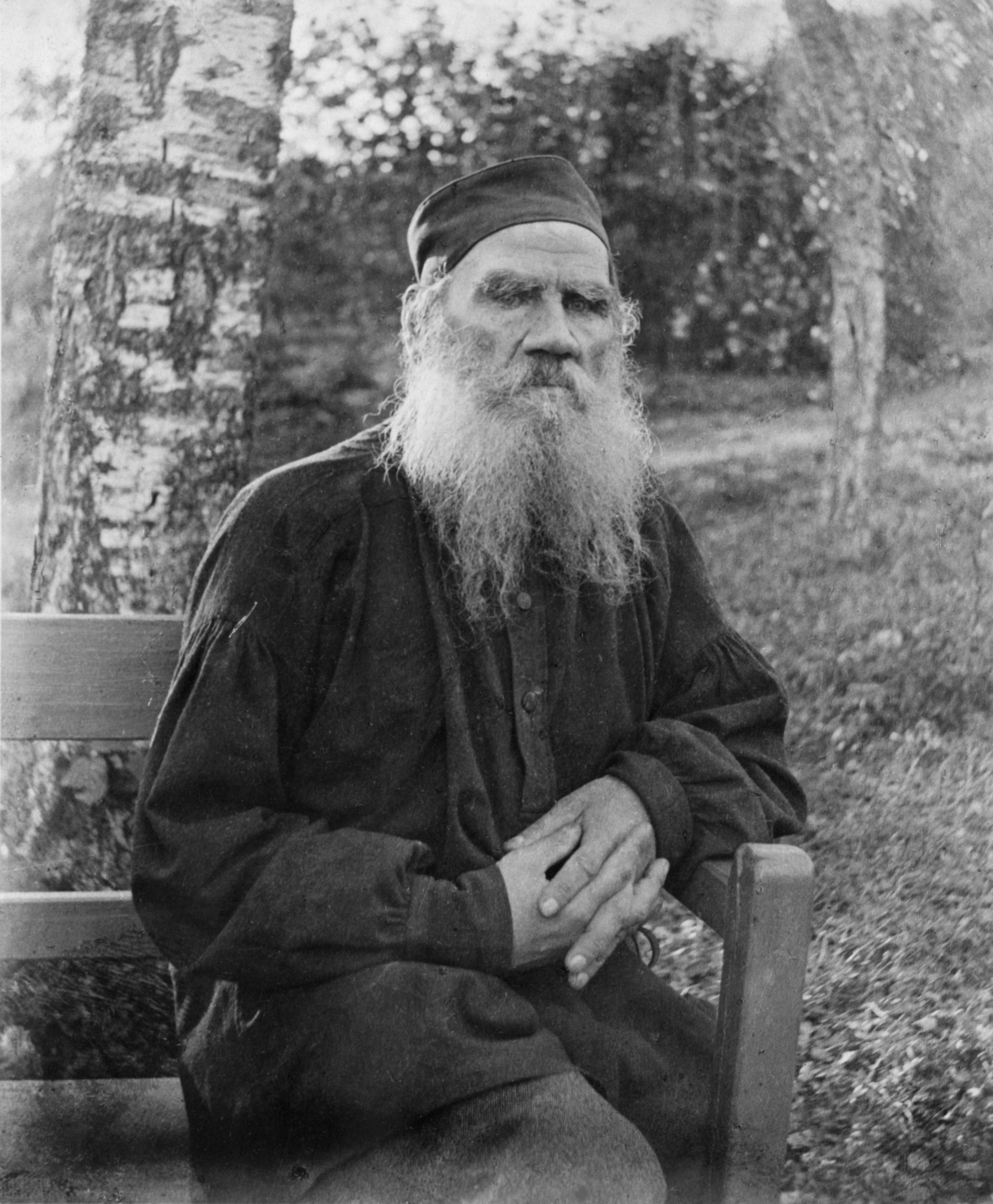

The Russian Leo N. Tolstoy (1828-1910) called the state the "founding devil". Understood with practical sense, he envisions a "kingdom of God on earth" – being freed from the hassle, oppression, addiction and violence of everyday life. Tolstoy prescribes voluntary, agreements and reciprocity. Central governments – including their cooperation with capital and the press – he describes as a "terrible machine of power" in which the majority suppresses the minority.

The Russian Leo N. Tolstoy (1828-1910) called the state the "founding devil". Understood with practical sense, he envisions a "kingdom of God on earth" – being freed from the hassle, oppression, addiction and violence of everyday life. Tolstoy prescribes voluntary, agreements and reciprocity. Central governments – including their cooperation with capital and the press – he describes as a "terrible machine of power" in which the majority suppresses the minority.

He may not have been that far from the truth, knowing today that there are more dictatorships and authoritarian policies than democracies in the world. Over 100 years ago, he suggested that ordinary people "fear bombs and anarchists, but not such a terrible device."

Like Kropotkin, Tolstoy believed at the time that technological advances would create more freedom, an "awakening from the sleepy conditions the government holds people in". Unlike the revolution, which he considers violent, he prescribes an individual revolution in which the self is to be developed, changed, and perfected. He also rejects consistent violence.

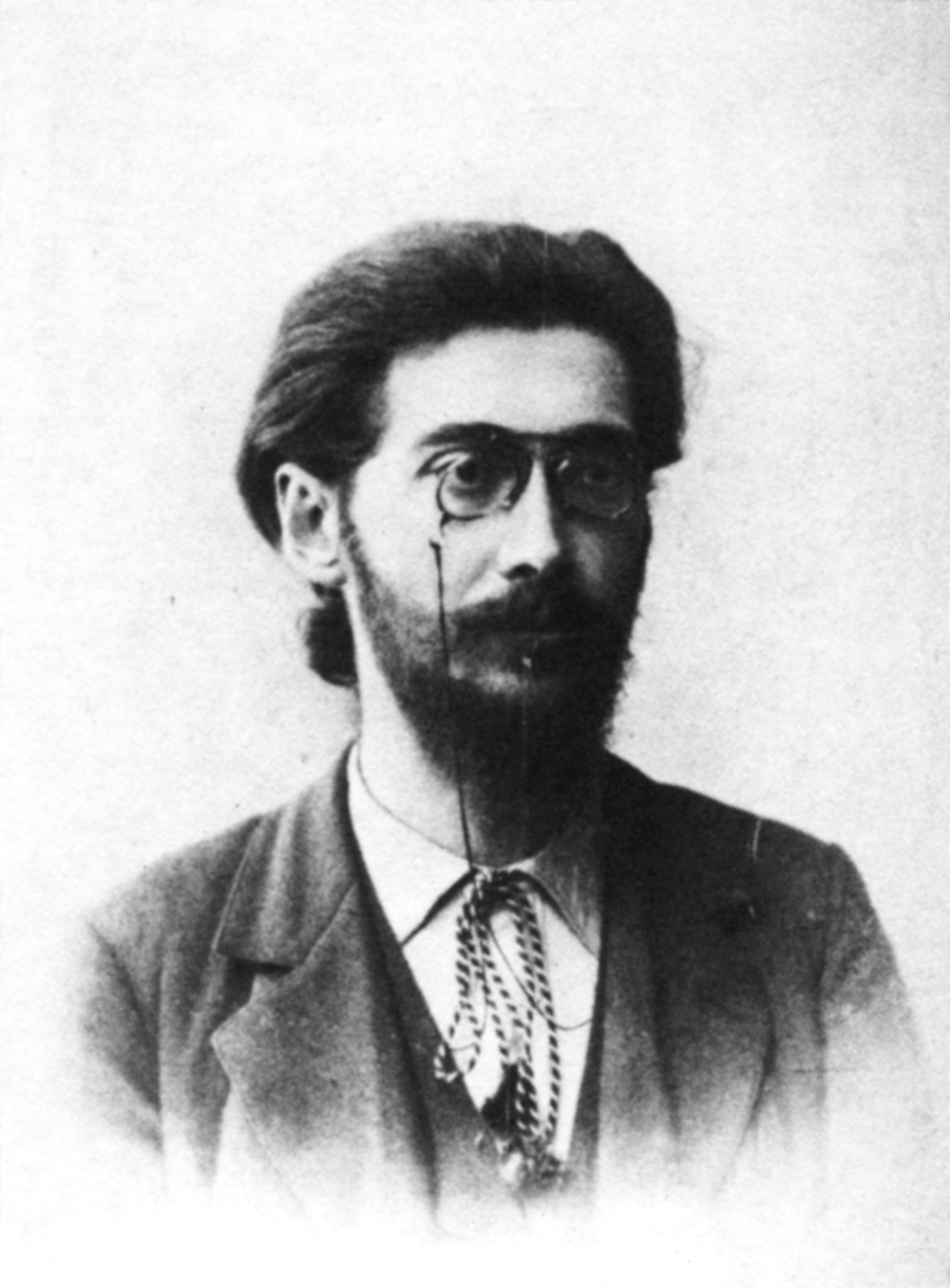

German Gustav Landauer (1870-1919), in turn, mentions Marxism "as the professor who will rule ... and proletarize large, monstrous and near infinite masses." For Landauer, "true socialism is a contradiction to the state and the capitalist economy. Socialism can only emerge from the spirit of freedom and voluntary entities. ” One should exercise one's sense of justice. His economic decentralization is similar to Kropotkin's with voluntary communities, and he is a strong opponent of violence.

German Gustav Landauer (1870-1919), in turn, mentions Marxism "as the professor who will rule ... and proletarize large, monstrous and near infinite masses." For Landauer, "true socialism is a contradiction to the state and the capitalist economy. Socialism can only emerge from the spirit of freedom and voluntary entities. ” One should exercise one's sense of justice. His economic decentralization is similar to Kropotkin's with voluntary communities, and he is a strong opponent of violence.

Finally, let's mention Emma goldman (1869-1940) who, among other things, worked for birth control, women's rights and against militarism. She was one of America's most important anarchists. Unlike Tolstoy and Landauer, she allows violence as a backlash to violence when "miserable living conditions offered no other option." But first and foremost, she considers people with a strong will and freedom of thinking as those who must lead a freer and better world for all.

Interestingly enough, she writes that the people are not the solution, as we may be used to thinking in Norway: She criticizes the people as a "compact mass" that "never works for justice and equality", but suppresses people's freedom of expression and spirituality. The people make "life monotonous, gray and monotonous like the desert." The people, according to Goldman, deny individuality, free initiative and originality.

Interestingly enough, she writes that the people are not the solution, as we may be used to thinking in Norway: She criticizes the people as a "compact mass" that "never works for justice and equality", but suppresses people's freedom of expression and spirituality. The people make "life monotonous, gray and monotonous like the desert." The people, according to Goldman, deny individuality, free initiative and originality.

Goldman is also known for promoting free sexual morality and having been opposed to the monogamous marriage – especially where the sex life becomes "socially beneficial within the marriage encroachment." For her, state and ecclesiastical morals are paralyzing, a skin morality that should make people compliant. She travels to Russia after being deported from the United States, but becomes even more disillusioned with their freedom struggle, as she puts it in 1922. The Bolshevik revolution she often considers more brutal than the way the Tsar treated the people, something both Stalin and history righted her in.

Despite all the setbacks and disappointments every anarchist has been confronted with over the years, Goldman was convinced that anarchism would one day become a reality.

Today, anarchism (in its more modern pragmatic forms) exists in a variety of minority communities, eco-collective or community-based, and lives well locally or in the small – without striving for a goal of state power, popular majority or the formation of political parties.

See Spanish separatists and anarchists are still fighting

Images from Wikipedia. Quotes have been taken from Hans Jürgen Degen / Jochen Knoblauch, Anarchismus. One introduction. (2008, Butterfly Publishing)