Forlag: Hanser Verlag/Suhrkamp Verlag/C. H. Beck Verlag (Tyskland)

(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

Fortunately, the 50th anniversary of 1968 in Germany is not celebrated only as positive or negative mythology, as we saw examples of in the previous Ny Tid. Heinz Bude sees the key to 1968 in trying to free himself from a false world of unnecessary consumption, prosperity and stupidity. Already in 1995 he published a book about the 68s, with the title A generation is getting older. Book of the Year, Adorno for the toddler, is a "remix" and update. 1968 is an association complex with many elements. Bude has asked selected 68ers what they themselves emphasized.

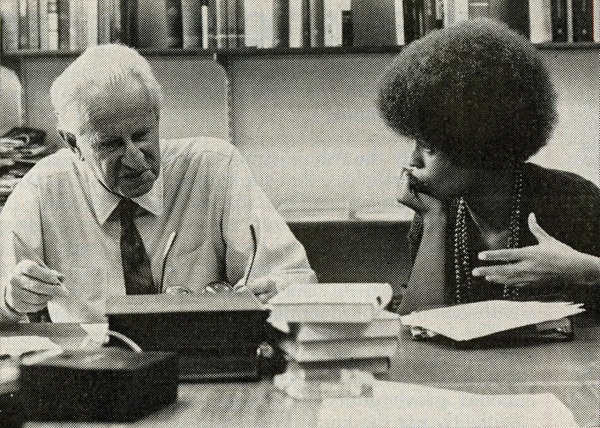

He has interviewed Peter Märtesheimer (born in 1937), who wrote the screenplay for Rainer Werner Fassbinder's film Maria Braun's marriage (1979). For him, the most important thing was getting the freedom to decide life for yourself. His father died at the front when he was three years old. Because he was small and thin, Peter was good at begging for food as a child. As a student in Frankfurt am Main, he was delighted by the lectures of the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno.

Klaus Bregenz (born in 1940) had working class backgrounds, but worked his way up to a position at the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, together with Adorno. His father was silent and drunk on the weekends. Bregenz perceived society as false and characterized by anxiety in relation to class, gender and generational differences. From Adorno he wanted to learn to survive.

Peter Gente, who founded the alternative Merve Verlag in Berlin, started reading Adorno as early as 1959-60 and lasted for ten years. Gente was 13 years old when he saw his father for the first time in 1951, when he finally returned from Russian war captivity.

feminists

feminists

Adorno was not as important to the women Bude interviewed. Adelheid Guttman (born in 1940) wanted to realize her own longing for transcendence and transformation. The Doors were more important than Adorno, Bude notes. Her parents were Nazis. She had felt leftist and cool (German: "customs") in -68. Now, in her old days, she considers herself a poster. Guttman became a feminist, separated from men and children, and joined the group Women and Film in 1974.

Camilla Blisse is one of the most important feminist theorists in Germany. Her father fell in the war, and she never needed a family. Blisse always experienced people who lived, or would live, in normal conditions such as stupid (German: "blöd") or boring. Now she plays Bach on the organ. The music was the rescue – not Adorno. She is disillusioned and complains that overarching political ideas have disappeared from the contemporary debate.

Fatless ruined children

In Germany, the 68th generation – which Heinz Bude confines to those born between 1938 and 1948 – had more traumatic war experiences than in a country like Norway. Many remembered the bombs, ruins and hunger from childhood. What is puzzling is how an abstract philosopher like Theodor W. Adorno could appeal to this generation of "ruin children". But he did, in fact, I have even spoken to people who claim that Adorno was the only one who broke with the rhetoric of "Germany's prosperity miracle" (German: "Wirtschaftswunder") in the early 60s.

Hodenberg will crush the notion of the loveless parents and the suffering sixty grandchildren.

In 1963, the social psychologist Alexander Mitscherlich wrote about the fatless society. He emphasized that fathers were absent in the home and did not serve as role models. But they were also literally missing. Gerhard Schröder never got to know his father, he fell at the front in Romania in 1944, the same year his son was born. Many of the fathers were missing or coming home as beaten men. They buried their past in silence and alcohol. A hard-to-reach philosopher that Adorno may have appealed to with his negative dialectics and the basic notion of "non-identity". For the philosophically interested, he put into words the emptiness many of the children of war felt inside.

"Pupp Assassination." When the students occupied a lecture room in Frankfurt in early 1969, Adorno called the police. Philosopher Herbert Marcuse disagreed with the decision and supported the students: “We cannot abolish the world the fact that these students are influenced by us (and certainly not least by you) – I am proud of that and am willing to come to terms with patricide , even though it hurts sometimes. ” (The correspondence between Adorno and Marcuse from 1969 is available online in English translation.)

Adorno had difficulty meeting himself in the door and perceived the demand for public self-criticism as pure Stalinism. He wrote to Marcuse that student actions exhibited some of the same mindless violence as fascism: students breathed life into fascism and mistaken revolution og regression. Adorno admitted that the student movement resisted the horror vision of "a thoroughly administered world," but also that the rebellion had a madness in it that pointed to the totalitarian.

The students turned to Adorno the same year he died. Among other things, the philosopher was subjected to a "puppet attack": Three students stormed the pulpit during the lecture and exposed their breasts. According to Hannah Weitemeier, who, unlike the other two women, has emerged afterwards, there was nothing political about the action. In an interview with Tanja Stelzer in Tagesspiegel (December 7.12.2003, XNUMX), she stated that Adorno's many women's stories were well known. A friend of hers had therefore suggested having "some fun" with Adorno's weakness for the other sex.

Consumption and violence

Alexander Sedlmayer's (born 1969) brick about consumption and violence in the Federal Republic convincingly documents how post-1945 marketing became an extension of the war by other means. The advertising used a military jargon: market offensive, advertising war, mass bombing, surprise attack. A basic concept at Sedlmaier is the "supply regime", a network of activities that connects consumption with power relations and prevents other forms of consumption and production. The book documents the connection between supply regimes and political protest.

Sedlmaier shows that "consumer terror" was already important in Ulrike Meinhof's journalistic work before the Rote Army Fraction (RAF) era. Many elements were included in the struggle against the consumer society: the Provo, which through actions tried to provoke violent responses through non-violent actions, and situationalism, which carried on the surrealist tradition and wanted to revolutionize everyday life. The assumption was that the working class was trapped by consumption and civilization. Already during an action in Munich in 1964, leaflets were handed out stating: "Love gave birth to the goods and paid tribute to them in false dreams and put them in a showcase so that people could no longer see their real wishes."

Burning department stores

After Munich, actions continued in Berlin. The student leader and Marxist Rudi Dutschke supported sit-ins in the warehouses as a form of late capitalist guerrilla practice. Growth in the German department stores in 1966-68 was over 20 per cent. The link between war, consumption and advertising is evident in Kommune 1 (a radical union of oppositionists) commenting that the largest Belgian department store burned down in May 1967, with 300 casualties: Under the heading "Why are you burning, consumer?" customers were compared to the victims of US napalm bombing in Vietnam. The fire was an advertising campaign: “A burning department store with burning people conveyed for the first time this crunchy Vietnam feeling of to join and burn with the others. "

Iconic images and single destinies have for too long characterized the German history writing about the 68s.

Herbert Marcuse's distinction between true and false needs was important. He wrote in Eros and Civilization (1955) that society's consumer compulsion prevents people from realizing life in a unique way. The system reduced man to work and consumption. Consumption was society's new ideology. There was even talk of "consumer fascism". The activist Dieter Kunzelmann had a background from Situationist International (SI), and the actions were obviously in agreement with Guy Debords (1931-1994) manifesto plays Society from 1967. Debord had already analyzed the riots in the Watts district of Los Angeles in 1965: The riots and looting were an attempt to break with the spectacular power of the goods. The essay was published with a photo of a burning department store in Watts on the title page.

The dynamics of capital

The first action of Baader and Esslin was the fire in the Schneider department store in Frankfurt in April 1968. In RAF's action against a department store in Frankfurt in 1968, we see the unity of the attack on consumption and against the Vietnam war. Consumption was perceived as a form of terrorism. "Consumption is terrorizing you. We terrorize the item. We terrorize the goods so you end the terror that makes you consumers. " Consumption corresponded in domestic politics to imperialism in foreign policy.

Most of Sedlmayer's book pursues political actions against the consumer community in various forms in protest of increased fares on public transport, house occupations and looting of shops, up to import boycotts of goods from South Africa and Israel, actions against the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, against sex tourism and fair trade actions against exploitation and child and women's labor in low-cost countries. These modes of action show the continuity from -68. But consumer criticism now argues more ecologically – one fights to a lesser extent against the product character as such.

The gender struggle was more important than the generational conflict in the 68 uprising.

It has been a tradition in Marxism to regard criticism of consumption as petty bourgeois, what one should focus on is production. But before one is given power to decide production, it can be controlled indirectly through consumer criticism and consumer power. However, trade based on fair trade principles, organic products and products with a low carbon footprint does not change the market economy system. Capital is frantically searching for new markets, new innovation, new and better products and new areas for consumption. The dynamics of capital's pursuit of profitable investments cannot be controlled solely by consumer power. Unfortunately, it shows the Sedlmaier's book to the full.

Fact-based demythologization

Historian Christina von Hodenberg adds The other -68 facts on the table that change the picture of some of the basic stories of the 68 rebellion. A common myth is that the rebellion is due to a displaced Nazi past on the part of the parent generation, who then came to the surface through the rebels. Hodenberg convincingly documents that this is a myth. She is based on one of Bonn's student leaders, Hannes Heer, who was made hereditary by a father with a Nazi past. But then she shows that such a conflict belonged to the exceptions: In a survey of 22 student activists from Bonn, only two mentioned that professors and politicians' NS past had contributed to their political awareness. More important was police brutality when it came to turning down student demonstrations.

Consumption was perceived as a form of terrorism.

Most of the student activists had not revolted against their Nazi fathers: There was little talk of such things at home. The young people failed to ask for consideration and closed the gaps in their parents' biography through imagination and empathy. Many of the activists came from socialist, communist or pacifist homes. Those with parents with a NS background tended to perceive them as innocent runners and not actual war criminals.

A broader perspective

Contention, breakage or emotional cold in the home was rare. The students knew little about their parents' background. Through selective narratives, and consequent tendencies, the myths gained freedom. The students combined an abstract understanding of Nazism with an apologetic takeover of family myths, Hodenberg writes. She wants to crush the notion of the loveless, mute parents and the helpless, suffering sixties. Certain iconic images and individual fates have for too long been characterized by German history writing about -68, she claims. In addition, the grandparent generation was more rigid than the 68's parents, so a three-generation perspective is needed. Hodenberg has come to the conclusions through a unique material, hundreds of hours of interviews of people of different generations done over 50 years ago under the auspices of the Psychological Institute in Bonn, which in the 1960s was the leader in age research and which Hodenberg has reinterpreted in light of the 68 rebellion.

Feminist tomato throw

The lifestyle changes were the most important result of -68, says Hodenberg. But the iconic portrayal of Rudi Dutschke, Rainer Langhans, Dieter Kunzelmann and other rebel heroes of this era, in Hodenberg's view, reveals that important things were happening in the privacy field. In the 60s, it was common for women to quit their studies and get married. Even those who were politically active were played on the sidelines as soon as they had children. They had to do the housework and often interrupted their studies because there were no nursery places. The men were keen to discuss politics, but less interested in housework.

Adorno was the only one who broke with the rhetoric of "Germany's prosperity miracle".

Feminism was initiated when Helke Sander presented himself as a member of the Action Committee against the oppression of the woman at a meeting of the German Socialist Student Union (SDS). When leading theorist Hans-Jürgen Krahl refused to answer the play, Sigrid Damm-Rüger (1939-1995) threw tomatoes at him. This action in Berlin in September 1968 gave the start of a new feminist wave in Germany.

Hodenberg concludes that the gender struggle was more important than the generational conflict in the 68 uprising.