(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

China has changed. Therefore, we must do the same. This is the essence of political self-awareness in large parts of the Western world. Over the past decade, China has developed in an autocratic direction with both excluding and expanding features. The reason for the West's concern is that politically and economically we are so connected to the Asian giant that even a partial secession is highly problematic.

Under Xi Jinping, China has closed like an oyster and at the same time invaded the rest of the world with its 'Belt and road' initiative, its monitoring and control of the Chinese diaspora – and its cultural export of, among other things, 525 Confucius Institutes worldwide. China's violation of human rights has been an irritation among Western democracies for a long time, without it significantly disturbing business agreements with the country.

But all this changed quickly after Russia's invasion of Ukraine. It finally became painfully clear that the mixture of politics and commerce involves dangers. And now we are confronted with a mighty China. The naive hope that it would become more like 'us' has dwindled. Now what are we to believe, or, what can we know at all?

Into a modern state

There are plenty of Western China experts, but how much do we know about what is thought and said inside China? The fact is that these are questions they themselves ask and seek answers to, exemplified in an 874-page anthology that has been presented and translated into German by Sinology professor Daniel Leese and journalist Shi Ming. In Contemporary Chinese thought. Key texts on politics and society a group of Chinese academics elaborate on topics such as 'what is China' and 'where is China going'.

There are plenty of Western China experts, but how much do we know about what the Chinese themselves think and say?

To define oneself on the basis of a civilization several thousand years old, multiple dynasties and dramatic political upheavals could seem worthy of a Sisyphus. In the words of Ge Zhaoguang, professor of history at Fudan University in Shanghai: "Until now, neither the history of philosophy nor the history of spirituality has addressed this larger context, although it is of great importance." He then deals with the transformation process from a traditional empire to a modern state. It included the merging of 56 ethnic groups. In order to adapt to the nation-state model, the 'Chinese nation' – with the poetic term 山川河流 (mountains and rivers) – first had to be created. This should be complicated enough if Japan had not also interfered and wanted to seize Manchuria and Mongolia.

This is the People's Republic of China, with a territory of 9,6 million square kilometers and a population of 1,4 billion people.

The nationality theme

Several of the anthology's chapters deal with the great task it has been for the citizens to identify with this state. Ge Zhaoguang: "The Chinese civilization, which we thought had universal validity, was replaced by another civilization from a foreign continent, the Western one. We had become a regional civilization.”

"The enraged people are no longer intimidated."

Here lies the seed of an identitarian antagonism. Little is written about the fact that China's Marxism was a Western import. But many words are used for criticism of the type: "Western states exploit the issue of nationality to split socialist states […] they use the so-called human rights and 'people's right to self-determination' as a pretext to interfere in nationality matters in socialist states. In that way, they support – explicitly or implicitly – the separatist activities of ethno-nationalist forces…”

In texts like this, one senses how exhausting it may feel to be an 'intellectual' in a system that increasingly decides what should be the line of thought for all citizens, under the supervision of 'Uncle Xi'. The identity issues continue.

Who is the farmer?

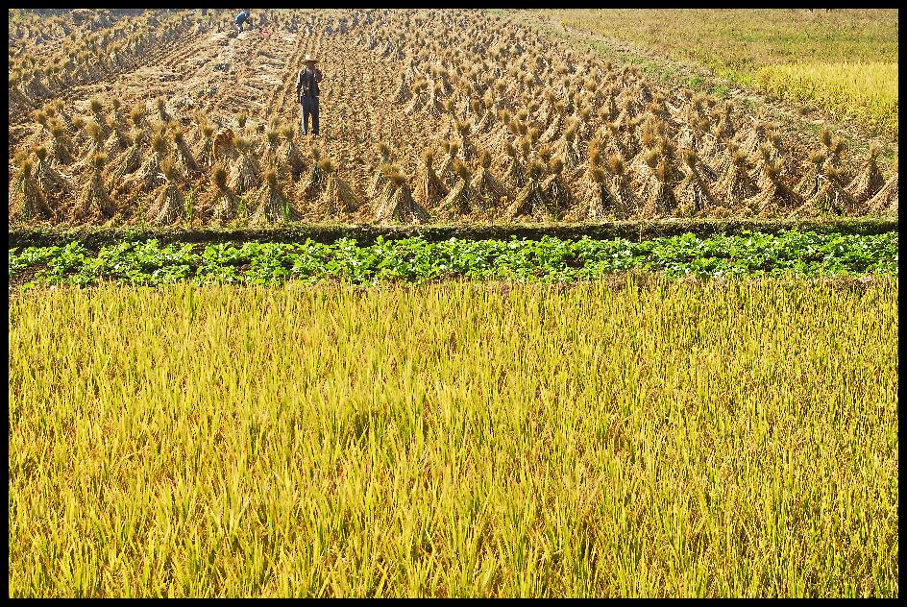

The peasantry gets plenty of space. He Xuefeng, a sociology professor at Wuhan University, states that since the peasants make up the largest part of China's working population, "most of them have made a gigantic contribution to the People's Republic". Nevertheless, they are still poorly paid and suffer from "multiple disadvantages". Nor are they a uniform group. Some own the land, some are only tenants. Some are ordinary small farmers who cultivate their own "contract land", some are "core farmers", who work under verbal agreements, some are state-financed family businesses, some are "professional farmers" who will take over responsibility for agriculture and phase out the weakest groups. All in all, a vulnerable group. The sorting continues until the end of the last chapter, with the sentences "Who is the farmer? Faced with this question, we should at least keep a cool head." A good start.

Female workforce

Another 'vulnerable' group is the women. There are very few female names in the text collection. One of them is Song Shaopeng, professor at the People's University in Peking. We are set in the period of Deng Xiaoping's reform and opening-up policy in the late 1970s. It was called "neoliberalism with a Chinese face". The policy garnered a lot of criticism with its privatization of the means of production, but not with its 'privatisation' of the family. It meant that the 'reproduction-related' work, especially birth, upbringing and care, was delegated to family members. During the "optimization using the regrouping of the workforce", female labor was first eliminated, explained with reference to (lack of) personal quality and competence. State enterprises no longer paid for their employees' 'human reproduction'.

Song wants gender equality based on business redistribution, cultural recognition and political representation.

As Song Shaopeng writes: "The reputation as inferior labor has led to a cultural devaluation and general rejection of women." What Song wants is gender equality based on business redistribution, cultural recognition and political representation. It is a valid wish but a long way to go.

Until the 1900th century, the feet of Chinese women were bound and deformed

- that is, those women who were not needed to provide (unqualified) work, for example in agriculture. Women achieved the right to vote in 1953. Still – in 2020, almost 42 per cent of applicants for doctoral degrees were women. Song's text appeared in Open Times magazine , in 2012.

"Conceptless tyrant"

A clue to China's academic freedom can be found in the years of publication. Most of the candid contributions were written in the period 2003–2005. After that it tightens. Around 2015, it is being feverishly discussed which political future one should bet on. Neo-Confucianism is widely supported, as is the government's algorithm-driven management, which is predicted to play a global pioneering role, with terms such as "the instrumentalization of credit data within surveillance capitalism". 'The digital personality' is praised as a victory. In line with the role models of the "magnificent Xi Jinping era".

Then – a bang. Xu Zhangrun, until 2020 professor of law at Tsinghua University, writes: "The enraged people are no longer intimidated." A frontal attack on Xi Jinping. His pandemic treatment is based on "spreading lies", and the political system is "morally bankrupt". The people are nothing more than a "source of looting", which the "internet police" does everything to support. At the top sits a "conceptless tyrant". The letter circulates on social media and abroad, while Xu is placed under house arrest.

See also the case Wang Huning – influential intellectual.