(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

There is a contradiction in the genre designation "science fiction", which in a sense becomes clearer by the slightly corny Norwegian translations "science fiction" or "science fantasy" proposed by Wikipedia. It lies in the concept that science fiction is fiction, and perhaps more than any other type of fiction, this genre deals with the really big hypothetical questions and thought experiments. But at the same time, science fiction's fiction and fantasy are based on science. Not necessarily with all of the research's demands for logical validity and verifiable, but this implies just as much a stronger anchor in reality and contemporary than one might think of this sometimes very escapist genre.

Sci-fi at Cinemateket. This spring, the Cinemateket in Oslo (in collaboration with the National Theater's "Sci-fi at Torshov") launches a science fiction series that will last for the entire 18 months, divided by a sub-theme for each of the three half years. The first of these is man, afterwards comes samfunnet and finally universe. (The films from the program mentioned in this article appear in January and February. Other titles will be included in the upcoming theme titles, as well as several sci-fi related events and special screenings this spring.)

It then makes absolute sense to begin with man, then considerations about it the human In the face of ever-more advanced, often independent thinking, technology seems to be the foremost theme in science fiction films and television series of the time. Lately, not least HBO series Westworld received much and very well deserved attention, as a fascinating thought experiment on real people and real raw material. The series asks ethical and philosophical questions about artificial intelligence and our need for ever more extreme entertainment, as well as being a story of storytelling – with all that entails of dramaturgical obligations.

With its ability to fantasize over philosophical as well as technological issues, science fiction appeals to many of us from when we are children.

Contemporary Relevance. I will not go into much more detail on this series, which has already been extensively discussed in Ny Tid a couple of issues ago – but it can still serve as an example that science fiction often discusses issues related to its own time, even if they happy to unfold in the future. This also applies to the new one Rogue One – A Star Wars Story, who, with his portrayal of guerrilla troops on some sort of suicide mission, has some clear parallels to current conflicts – even though the film is primarily an entertaining and action-packed adventure from a galaxy far, far away.

In this context, one should also not forget that series Westworld is based on a feature film of the same title from 1973, written and directed by Michael Crichton, which appeared on Cinemateket as one of the first films in this recently begun series.

Artificial intelligence. For though robots and artificial intelligence have become central and widely discussed parts of the escalating technological development of recent years, this has been themed in science fiction films and literature from the very beginning. One of the first sci-fi feature films, Fritz Lang's massively influential one Metropolis from 1927, for example, is about a robot designed to pretend to be a specific human being. (Note, however, that the movie Metropolis which will be shown at the Cinemateket in late January is Japanese Rintaro's animated film from 2001, based on a 1949 multi-feature series with the same title – which in turn is only inspired by a still image from Lang's film.)

Created a monster. However, the science fiction genre emerged a good while before the movie medium, in many people's opinion with Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein (anonymously published in 1818, originally with subtitle The Modern Prometheus), which is just about a scientist creating artificial life, and the moral issues associated with it.

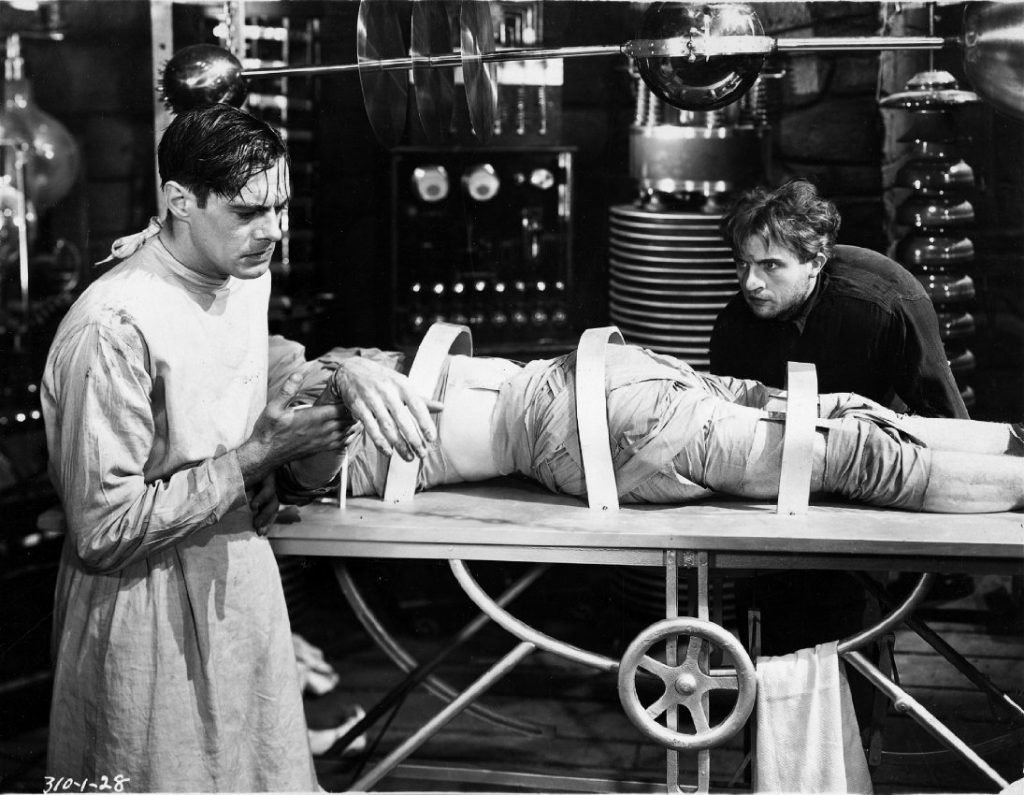

Suitably, the Cinematheque shows one of the many filmizations of the book, more specifically James Whale's classic 1931 version with Boris Karloff in the iconic monster role. The well-known story of the professor who creates a thinking monster was written during the industrial revolution, and can be interpreted as a warning against this development, or more specifically against tampering with nature. And with this, it establishes a striking feature of many science fiction stories: a distinctly optimistic belief in the potential of science, combined with a correspondingly strong pessimism for its consequences.

Social Criticism. The monster in Frankenstein is portrayed as a sensitive being, in a narrative that was also groundbreaking within the horror genre. Other sci-fi stories in the borderland against creepers make a point out of portraying characters without emotions, often based on the idea that emotions are an essential element of our humanity. The Cinematheque shows Don Siegels Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), which is about a small American city where more and more of the population suddenly change personality, first and foremost as their feelings disappear. The film can (among other things) be read as an allegory of what dreaded communism could do to the population, and is thus also a science fiction film that plays on currents and attitudes in its time.

A related movie is The Stepford Wives (Bryan Forbes, 1974), which also appears in the program series. Here is depicted another small town, where all the housewives are frighteningly perfect until the robotic. This is a film that obviously ironizes about the role of women in society, hardly regardless of the rise of feminism in the seventies.

One can see a tendency for the stories to no longer contain traditional monsters, but rather to discuss who the monsters really are.

Reason and feelings. More direct social criticism will probably be found in the film selection for the next theme section, which should therefore deal with samfunnet. In the first volume, issues related to artificial intelligence appear to be a more pervasive trait, which in a sense is natural enough for sci-fi films focusing on man. This time, though, Stanley Kubrick's masterful does not appear 2001 – a romodyssé, who with the computer HAL 9000 has been schooling for the genre's depictions of rational machines that invoke emotions. However, this is a movie that contains virtually all of the sci-fi genre's core components, and which may be just as relevant to show when looking at the universe.

A similar computer that tries to take control of its surroundings – and even acquire a progeny – is found in the more obscure Demon Seed (1977), an ever-so-small cult gem of a sci-fi horror directed by Donald Cammell (his first feature film since the hefty debut Performance from 1970, which in turn was co-directed by Nicolas Roeg). Artificial intelligence is obviously enough theme in Steven Spielberg's AI Artificial Intelligence (2001), the film project originally started by the aforementioned Stanley Kubrick – but also in Ridley Scotts Blade Runner (1982) and Alex Garlands Ex Machina (2015)

The latter is also a chamber game, and demonstrates that science fiction is as much dependent on interesting basic ideas as on advanced special effects. The same goes for Ducan Jones' Moon from 2009, which also asks big questions (in this case about cloning) with easy means.

Man as a monster. Furthermore, one can see a tendency that the stories no longer contain traditional monsters, but rather discuss who the monsters really are. This question seems to emerge more or less automatically with the premise that man can create life, which is then able to reflect on his man-made existence.

HBO series Westworld (where it certainly reappeared) is quite radical in that sense, as it eventually draws a picture of humans as the actual monsters, while sympathy seems to lie with the humanoid machines. But this is also an underlying issue in the aforementioned Blade Runner (by the way, another masterpiece within the genre), which also portrays human-like androids rebelling against their creators – and has undoubtedly been a source of inspiration for the creators of Westworld.

With its ability to fantasize over philosophical as well as technological issues, science fiction appeals to many of us from when we are children. One can probably also assume that most researchers have grown up with such stories, and that this has created a certain interaction between science og TV series: Fiction further dictates science, but science undoubtedly also draws inspiration from poetry. Currently, we are reportedly in an upheaval comparable to the industrial revolution, where machines are not only going to take over manually, but also a lot of intellectual work. In other words, it may seem that many of the elements that previously only belonged to science fiction are becoming part of our reality – which is met with both optimism and anxiety. And while it is tempting to say that life with this imitates art, I should just point out that developments have at least made such stories even more relevant to the time we live in.