(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

"Today's laws on copyright and patents create an intellectual monopoly more than they secure intellectual property," Brink Lindsey and Steven Teles write in their recent book on the US economy. The concern that "overprotection" of intellectual property should be an obstacle to innovation and dissemination is not new. But it has become more prominent now that knowledge stands out as a competitive advantage and a dominant driver of economic activity.

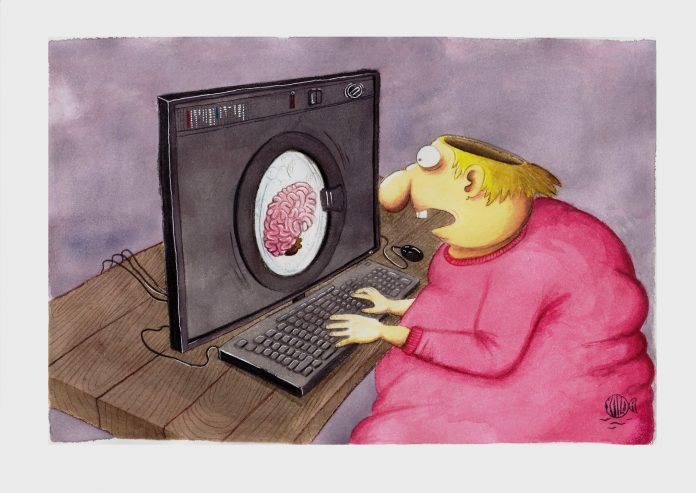

Digital technology has made the emergence of an "intangible economy" possible, based on soft assets such as algorithms and code strings, rather than physical assets such as buildings and machines. Under such conditions, intellectual property rules can create – or destroy – business models and transform societies by deciding how financial benefits are distributed.

patents

But the main elements of today's IP regime were established for a completely different economy. Patent rules, for example, reflect the tenacious assumption that strong protection provides an important incentive for companies to continue innovating. Indeed, new studies by, among others, Petra Moser and Heidi Williams find little basis for the claim that patents stimulate innovation. On the contrary: As they lock in the patent holder's benefits and drive the cost of new technology in the weather, this type of protection is associated with less new development and lack of subsequent innovation, weaker dissemination and increased market concentration. This has contributed to greater monopoly power, it has slowed productivity growth and led to increased differences in many economies over the last couple of decades.

Politicians should democratize innovation to stimulate innovation.

Patents also encourage significant lobbying and increased manipulation of financial and legal matters. The majority of patents are not used to produce commercial assets, but to create a defensive legal will that can keep potential competitors at a distance. As the system expands, patent fixing and litigation increases. Claims filed by patent litigants make up over three-fifths of all IP offenses in the United States, costing the economy about $ 500 billion over the years 1990–2010.

Some argue that the patent system should simply be abolished, but that would be a too radical approach. What is really needed is a complete overhaul of the system, with the aim of changing excessive or rigid rules of protection. The rules must be in line with the current reality and facilitate competition to stimulate more innovation and the spread of technology.

Re-form

A set of reforms that should be considered concerns the improvement of institutional processes, such as ensuring that those who hold the patents are not taken into account to an excessive degree. Other reforms apply to the patents themselves, and involve shorter patent durations and the introduction of "use the patent, or lose it" regulations, as well as stricter criteria for granting patents so that they are only granted for truly meaningful innovation.

The key to success may lie in replacing the "one-rule-fits-all" approach that the existing patent regime operates on, rather than introducing a differentiated approach that is better suited to today's economy. Patents have a lifespan of 20 years (copyright valid for 70 years or more). But while a relatively long patent term may well suit innovations in the pharmaceutical industry – which include lengthy and costly testing – it is less appropriate for most other developers in the business world. For developers of digital technology and software, for example, which require much shorter development time and which build on previous innovations in a stepwise development, a significantly shorter patent period would be more appropriate.

Of course, if those who are to regulate this decide to tailor patents to different types of innovations, they must be wary of complicating the patent regime to an excessive degree. Finding the right combination of reforms will inevitably require experimentation and close monitoring of the consequences, so that necessary adjustments can be made along the way.

But designing the right reforms is only part of the challenge: strong capital interests will make reforms difficult to implement politically. Fortunately, the circumstances could not have been more favorable for a reform of the decades-old patent system. If the system's defenders really want to promote innovation, they should welcome it into their own backyard.

The public

However, patents are not the only important element of the innovation ecosystem: The public sector also promotes innovation through direct funding of research and development (R&D) and through tax incentives. Changes are also required in this field. Public expenditure on R&D aims to help the general public benefit from basic research, which often produces a surplus of knowledge that benefits the entire economy. But in the United States, the government's commitment to R&D has fallen from 1,2 percent of GDP in the early 1980s, to half that level in recent years. This underscores the need to revitalize public research programs and ensure broad access to the findings they make.

In addition, R & D incentives for the business community – tax breaks, grants and the distribution of prizes – must be made available to companies in a fair way. A patent reform could complement this type of reform, for example by banning patents on publicly supported research, which should be available to all market participants.

Many innovation breakthroughs that have been commercially developed by private companies actually come from publicly supported research. Recent examples include Google's basic search algorithm, key parts of Apple's smartphones, and even the Internet itself. The authorities should consider how they can give taxpayers a share of such profitable results of publicly supported research, not least in order to be able to defend increased public R & D budgets. Here, the tax system has an important role to play.

In a broader sense – in an increasingly knowledge-intensive economy – politicians should make sure to democratize innovation to stimulate innovation and the spread of new ideas as well as promote healthy competition. This means overhauling the system that is supposed to preserve intellectual property, because as it is today, it is moving in the opposite direction.