(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

"My mom taught me that not only is it important to be considered, but also to be the one to be considered," Beyoncé told US Vogue in September. In her much-talked-about interview, she points out that "not only is an African-American on the cover of Vogue's most important monthly edition, but it is also the first cover photo in Vogue taken by an African-American photographer". A number of other magazines have also had colored women on the cover lately. And what's more: The chief editor of English Vogue, Edward Enniful, is – for the first time in history – a black man. All this just over the course of a year, where Hollywood has for the first time had a bestseller with a black hero, Black Panther (2018) – a movie set in Africa, where almost all the actors are dark-skinned, and where the film also has a dark director.

But isn't it the opposite that should really amaze us? How come it is only now, more than a hundred years after the film's invention, that the cultural industry hires African Americans and furthermore adjusts the photo techniques so that they can work for those with darker complexion as well?

The Conquest of the Louvre

It is in this context that Beyoncé and Jay-Z – the American pop idols who together go by the artist name "The Carters" – launch their latest projects: the album Everything is love and their On The Run Tour II. They have opened doors for their African-American artist colleagues, both younger and older. The tour poster is a direct reference to one of the most important African films ever made, Touki Bouki (1973) – a feature film by Sinhalese director Djibril Diop Mambety. Now they have conquered the Louvre – the temple of European culture – as the location for the video "Apesh ** t" from their album Everything is Love, and thus prepares the text for the audience: "I can't believe we made it".

It is in this context that Beyoncé and Jay-Z – the American pop idols who together go by the artist name "The Carters" – launch their latest projects: the album Everything is love and their On The Run Tour II. They have opened doors for their African-American artist colleagues, both younger and older. The tour poster is a direct reference to one of the most important African films ever made, Touki Bouki (1973) – a feature film by Sinhalese director Djibril Diop Mambety. Now they have conquered the Louvre – the temple of European culture – as the location for the video "Apesh ** t" from their album Everything is Love, and thus prepares the text for the audience: "I can't believe we made it".

In the past, Africa was often seen as a kind of eternal museum that had no history of its own, so Europeans could appear as the real bearers of history.

In the video, it is the Carter duo that has the power. They have occupied the elite's premises and challenge the expected way in which Africans have been viewed. As several critics eagerly noted, most of the works of art that appeared in the video were images depicting Africans – from Théodore Géricault's "Le Radeau de La Méduse" ("Medusa's fleet", 1819) to Marie-Guillemine Benoist's "Portrait d› une " négresse ”(" Portrait of a Negro ", 1800) – a picture that in its time was one of the few works of art that showed a dark person as the main motif. By putting themselves in a position where they are "considered", in parallel with the couple also assuming the role of viewer, they celebrate the beauty through an exquisite choreography and an extravagant appearance. At the same time, they are throwing away wreckage at the rigid museum institution and transforming the Louvre into a marker for their own success.

Africa as a meeting point for Europe's demons

Indeed, the appropriation of high culture is one of the most prominent creative strategies of contemporary visual culture. Many other artists have recently used the Louvre as a setting for their projects – not least Tony Morrison, who organized a poetry slam in front of the aforementioned painting by Géricault. Carters has already, though somewhat controversially, referred to works by prominent visual artists: Jay-Z to Marina Abramovic and Beyoncé to Pipilotti Rist.

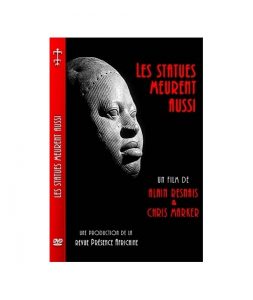

Behind this coincidence between popular culture and the elite that is celebrated in the exclamation "We made it!", There is another, more ambiguous aspect. The benevolent assumption that Carters with his presence in the Louvre in his "Apesh ** t" video has established himself as both heirs and outsiders, can be understood in several ways. This is themed directly in a much older and less popular film, Les statues meurent looks (Also statues die), produced in 1953 by the journal African Presence, directed by Alain Resnais and Chris Marker.

The two renowned French filmmakers had originally set out to make a film about African art that was little seen and appreciated in France in the 1950s, but in the run-up to the film they began to wonder (in Resnais' words) «why art from black Africa is located in the Musée de l'Homme (an anthropological museum), while Greek and Egyptian art are located in the Louvre? ».

This is thematized directly in a much older and less popular film, Also statues die, directed 1953 by Alain Resnais and Chris Marker

In his poetic text which is the narrative trace of the film, Marker was critical of the colonialist view of African art as primitive and European art as classical. He argued that African art fades when taken out of its original context, but he nevertheless did not try to restore an original perspective. Instead, he used the film language to give a new life to the art objects. In the past, Africa was often seen as a kind of eternal museum that had no history of its own, so that Europeans could appear as the real bearers of history. But this film – which showed different images of Africa from different historical periods – defined Africa as a continent with its own history. Objects from Black Africa, which in the movie are presented from different angles and through sequences of close-ups that move and live their own lives (a technique Marker develops to the full in La Jetée (1962) – a film that consists almost entirely of still images). At this point in the film, where Africa appears in all its diversity and variety, Marker's text also becomes critical of colonialism's racial practices – from seeing Africa as a projection of Europe's demons, to the exploitation of traditional art – yes, to and with their dark bodies as athletes and musicians in popular culture. The film ends with black African masks and a celebration of unity, for as Marker wrote, "there is no rift between African civilization and our own." The faces of the black art were drawn from the same human face, such as the skin of the snake. "

A mark of the unknowable

With its fast movements, more and more bubbly and ecstatic, the cinematic display of African masks feels at the end of Also, statues die, as a predecessor to the "Apes ** t" video. Indeed, the "Apes ** t" video itself appears as a mask: a symbol that, with the two stars in the video's official name, marks the unknowable and covers the obvious at the same time. The dance sequences and Carter's ever-changing outfits and style open up a carnival-like space, pointing to another legendary blend of popular and elite culture, where apes emerge in the title: See Jungle! See Jungle! Go Join Your Gang Yeah! City All Over, Go Ape Crazy. Bow Wow Wow's first studio album was produced by legendary punk producer Malcolm McLaren, who used carnivalesque elements in a more direct political way, and is close to Bachtin's interpretation of carnival's role in medieval Europe. Once a year, the carnival allowed the people to criticize their superiors freely. The record cover showed the band in it recreating Édouard Manet's "Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe" ("Breakfast in the Green", 1863) where singer Annabella Lwin poses nude. She was 14 at the time, and the band was accused of exploiting a child with immoral intent. For the band's fans, however, this was a form of ironic identification, a provocation, just like McLaran's previous punk projects, which mocked the hypocrisy of the powerful in the community, and exploited the sexuality of teenagers when they needed it.

With its fast movements, more and more bubbly and ecstatic, the cinematic display of African masks feels at the end of Also, statues die, as a predecessor to the "Apes ** t" video. Indeed, the "Apes ** t" video itself appears as a mask: a symbol that, with the two stars in the video's official name, marks the unknowable and covers the obvious at the same time. The dance sequences and Carter's ever-changing outfits and style open up a carnival-like space, pointing to another legendary blend of popular and elite culture, where apes emerge in the title: See Jungle! See Jungle! Go Join Your Gang Yeah! City All Over, Go Ape Crazy. Bow Wow Wow's first studio album was produced by legendary punk producer Malcolm McLaren, who used carnivalesque elements in a more direct political way, and is close to Bachtin's interpretation of carnival's role in medieval Europe. Once a year, the carnival allowed the people to criticize their superiors freely. The record cover showed the band in it recreating Édouard Manet's "Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe" ("Breakfast in the Green", 1863) where singer Annabella Lwin poses nude. She was 14 at the time, and the band was accused of exploiting a child with immoral intent. For the band's fans, however, this was a form of ironic identification, a provocation, just like McLaran's previous punk projects, which mocked the hypocrisy of the powerful in the community, and exploited the sexuality of teenagers when they needed it.

Other wins to win

Similarly, Carter's exclamation "I can't believe we made it" is not just a joyous celebration of their own success. It is an ironic identification, and as such it is also a recognition that beyond personal success, there are other struggles to be won. The appropriation of the high culture and the self-referential reference to the monkeys are two common features of the two songs. But there are also the bodies – the bodies of workers, the bodies of teenagers, the bodies of dark-skinned people – who in a carnival-like manner celebrate their freedom and the liberation from oppression. The references to the apes, to the animals, imply an oppression in which the humanity of the oppressed is deprived. And it is the oppression, according to Marker, that unites color and white: oppression is what we have in common.

“It would not be something that could prevent us from standing together – heirs of two pasts – if such a similarity could be resurrected in our own time. Unless it is anticipated by the only equality that benefits everyone, being oppressed. " Therefore, it is necessary to look behind the mask and look for what the unknowable can tell us.

"Apesh ** t" is not "ape crazy". Ape crazy is, as in the title of the first Bow Wos Wow album, a pure celebration. "Apesh ** t" as in "Have you ever seen when people get Apesh ** t" in Carter's song – to quote directly from the slang dictionary: "When someone gets so pissed that it's just before they start to as much as monkeys do. " Anger. Beyond this, once again in Marker's words: “We sense the promise, common to all great culture, of man overcoming the world. And whether we are white or black, our future is brought about by this promise. "