(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

The other day I saw the new documentary Marianne & Leonard – Words of Love, a film about the love story between Canadian songwriter Leonard Cohen and his Norwegian muse Marianne Ihlen. But it is also a movie about the magical time of the sixties on the Greek island of Hydra, about experimenting with life, body and nature. People went to the Greek islands to find other communities and a different life, start a conversation with place, people and nature. Of course, it got a kind of page with drugs and lonely children left to themselves.

But even today there is a longing to explore life and communities in new ways. Born of uncertainty in politics and economics as well as existentially – that we are all exposed. Also in recognition that our educational and cultural institutions are in crisis. A sense that communication and discourse struggles have lost the ability to express our contemporary. That we need alternative narratives that do not fall into nostalgia, concept and nation worship, need new tools to think about. New experiments to learn to watch. It is becoming clear to us that what surrounds us human beings is far more than human communities. That we are surrounded by nature, places, things, animals, machines, networks, sign systems. That we are involved in complex, temporary and flat systems for which we are responsible. We live a life in makeshift spaces. A life in multiple media, multiple places, all at once. A life of contemporaneity, a life of archival characters and images.

It is the collector's tale, the wandering, the feminine. The body as grassland.

That is in the light of all this we must see Mjøsa – an art project and the conference "New Territories? Decentralized art practice ”(Hamar, March 28). In a collaboration between seven municipalities, Mjøsa has created the basis for a hybrid knowledge building in which arts, technology, nature, economics, crafts and cultural communication have paved the way for a new type of social innovation. Thereby also a rare bridge between thoughts on life form and art on the one hand and cultural dissemination and documentation on the other.

Sense of place

To conclude a 5-year long knowledge building with art in the landscape around Lake Mjøsa, which is Norway's largest lake – over 10 kilometers long and a beach of about 40 kilometers – 12 artists have had 2 ½ years to choose, perform and edit. a work. Everyone has a special affinity for the place.

These are works that connect with the elements of the place, which use the elements of the place to think about: colonnade Helgøya (Espedal), making use of the site's vegetation; sculpture Prosthesis and visor (Olsen), who uses stones from Mjøsa's beach to show other ways to create repair and protection; sculpture The sky is cloudy (Kurd beer) located on the beach edge that explores the relationship between protection and belonging. Several of the projects confirm what I call a resonance between man and the non-human: that the work of art creates connections and relationships of strength between elements that were previously part of other connections: fragility and substance (handling, Österberg); time and the grief of history (The sound of tgo, Aagaard) and the earthquake (End of the world, Li Stensrud) – where both the elements and the time work together.

The relatively long period of creation has opened up an important conversation with the place around the lake. A conversation characterized by an "open situation" (Per Bjarne Boym), in which the way the place affects the artist, is at least as central as how the artist influences the place.

Today, many places have been transformed into abstract spaces (urban spaces, landscapes) endlessly reproduced. What we need is sense of place, an active acquisition of places, objects, smaller spaces, not the big horizons, but spaces in which we can practice sensing and experience – hence the title of Mjøsa's art catalog: After all, there was no horizon there.

The cultural carrying bag

The idea of «decentralized art practice» is partly to challenge the center and predictability of power (museums and cultural institutions) and partly to use the artwork to create new landscapes, new ways of looking.

Perhaps we might as well see Mjøsa as a bid for what American author Ursula K. Le Guin calls a carrier bag theory for art practice: “We've all heard all about all the jaws and spears and swords, the things you can hit and punch with , the long, hard stuff, but we haven't heard of the thing to put things in, the container of the retained thing. It's a new story. And yet old ”(Ursula K. Le Guin: The carrier bag theory of fiction, translated by Karsten Sand Iversen, Publisher Real 2017). She says we can easily see the artwork as a sack, a bag, a medicine rack that holds things in a particularly powerful relationship with one another. A showdown with the nostalgic linear narrative, the urban center search, the smooth facade, the demand for possession. It is the collector's tale, the wandering, the feminine. The body as grassland.

The poet has always addressed things and nature because the inquiry makes things, stones, trees, water, a responsive object to which you can speak.

We can relate to foreign bodies that affect our lives, extinct animals, things, plants, the teachings of their active power, their patterns.

We can rethink our place in the world, break down barriers, build a different sensibility.

We can ask ourselves if the constant focus on work, bustle and productivity removes us from a neighborhood of things.

And what happens when there are no real objects for politics and art, but only what we can think of them ourselves? Palmyra, Aleppo, the Bamiyn Buddhas, things, objects that have been destroyed in recent years. And every day there are people who can feel that something is breaking in them too. The special neighborhood of things is the bearer of clues, stories, distance and proximity. Places that, together with those who visit them, are the bearers of a story that individually stores or unfolds something.

Immigrants and refugees

The panel discussions at the event at Mjøsa last spring talked about how to make art viable, how to ensure dissemination and documentation. Mjøsa has taken up the fight against the strong cultural institutions and museums, and the municipalities would like to follow up with documentation to preserve this narrative. But, as always, limited funds and special interests are at stake.

A radical rethink can involve a more non-state anarchist approach where the contractor and avant-garde meet to do it themselves.

With inspiration from a meeting I had a few days before at the State Museum of Art in Copenhagen, about the working conditions of artists, I proposed to the curators and municipal staff at Mjøsa to give free space to more refugees at the arts and cultural institutions. Throughout the 20th century, immigrants and refugees have always formed a vanguard in the avant-garde. Those who cross borders that create shakes and new exchanges have always been part of the crucible. Sometimes you have to go untraditional. And perhaps the uncertainty of time, the political, economic and existential vulnerability we all feel, calls for radical rethinking? A more non-governmental anarchist approach where the contractor and avant-garde meet to do it yourself.

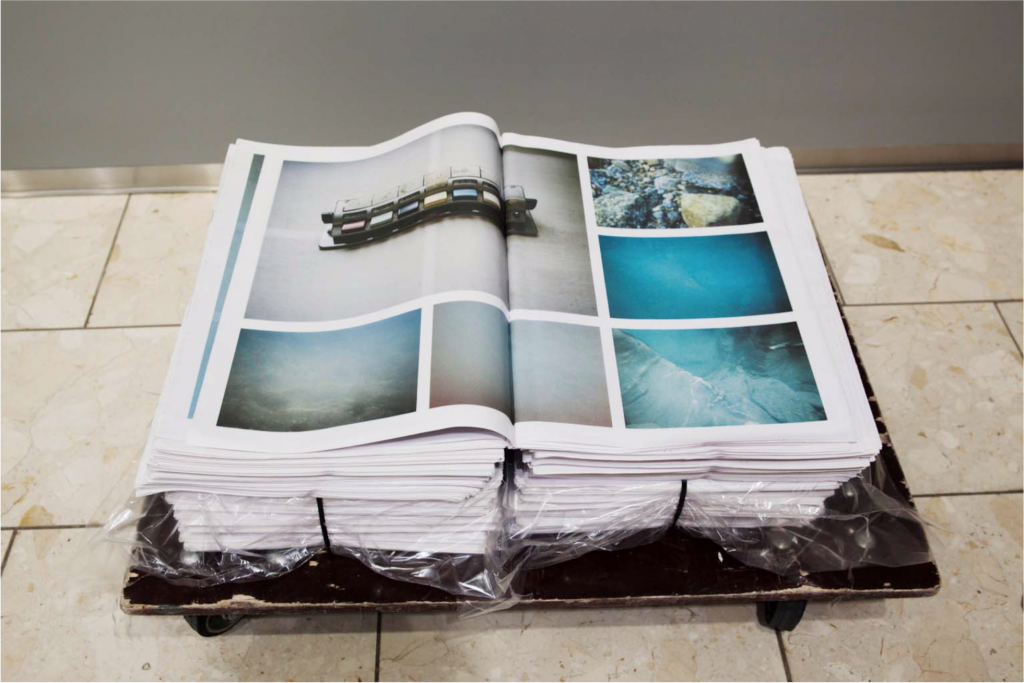

PHOTO: PER ERIK FONKALSRUD

The message today is clear: If you want something new, do it yourself. New thinking and new initiatives have difficulty penetrating the established institutions, whose money often seems earmarked for experiential economics, optimizing quality of life or investment potential. And as I said in my lecture, it is as if established art criticism and social criticism (post-Marxism or critical theory) has lost its ability to capture and accommodate our contemporary. The old theories are totalizing and do not have the tools to break the discourses, to create entirely new conversational spaces and yes, to think and implement change.

The municipal manager of the Mjøsa project, in his closing speech, was not at all dismissive of my proposal for more refugees for refugees! Either way, Mjøsa should become a role model and inspiration for other cross-cutting art initiatives around Scandinavia.

Mjøsa – an art project took place at Norway's Great Lake, where 12 artists worked from 2016 to 2018 and in exhibition spaces around the entire lake created works that can be permanent or temporary in the landscape. The conference last spring was based on this project.