(THIS ARTICLE IS MACHINE TRANSLATED by Google from Norwegian)

A young woman is moving around an uninhabited no-man's land, under the city of Bethlehem, which has burst into the air following an ecological disaster. Along the way, she has a conversation with a survivor from the past about memory, history and identity. The color gamut of the film is similar to viscous oil. A physical print and a picture on a heated globe. The 27 minute movie In vitro is the Danish contribution to the Venice Biennale, which has just opened and is created by the Danish-Palestinian arts Larissa Sansour. A powerful both poetic and political film that keeps disillusionment open as a way of life.

The film's action takes place under the Palestinian city of Bethlehem and revolves around the aftermath of the disaster, being in a limbo, neither condemned nor saved. Central to this is the conversation between an older woman lying in bed and a younger one who has grown up in the post-destruction era. For the elderly, life must be built on past and memory. For the younger, the past and the memory are only symbolic nostalgia. For the elderly, the city is a home, for the younger one an abstract claim of a broken world. The idea of a home is dispelled. The film's sci-fi grip allows for a different exploration of the conflicting geographical space between Israel and Palestine. Time is literally sinking into space like a prison. For how are we to understand tales of belonging and the past when everything is destroyed? With his film, Sansour casts a speculative sci-fi fiction into poetic-existential alloy – a particularly alien beauty. A prophetic but universal view of the Israel-Palestine conflict, about who we are, about belonging, about the uncertainty of what is to come.

In the room opposite stands a monument of lost time. A sculpture that exhibits darkness, the trauma, which absorbs all energy, which swallows the future, the time that seems to be lost all the time. But my first thought when I left the film in the Danish pavilion was: also a loss for us Danes who operate in a world without conflicts and wars in life, a world where we risk nothing and who has lost the sense of life's tragic sides. Maybe that's why we sit on clinker from Palestine while watching the movie, to feel the heaviness, the energy, the clash?

Melancholy, intimacy, horror

English Ed Atkins as part of a larger multi-installation (Old Food og Good man) created a series of computer-generated videos that portray himself and others affected by some kind of unexplained mysterious crisis. The half-artificial and half-real faces move their heads in strange twitches, while a viscous fluid-like cry runs down their cheeks. A seemingly endless cry. The digital sentimentality turned into an unheard of intimacy.

I was back twice to see these portraits. Why is man crying? Because otherwise it wouldn't be able to tell the truth? Because the truth must feel with the whole body before the true shows up before we can be true? Because true compassion also involves a readiness to feel pain? Even though these faces are haunted by horror, by spasms, by dummies.

Immediately far from and yet not yet hears Atkins' second video of impossible barley-self burgers assembled and collapsing in a creepy McDonald's advertising imitation. First the bread dips down, then the salad, then the cucumber, but instead of a steak it topples down with human bodies, babies, or facial skin similar to ham, then ketchup and chilli mayonnaise. The top loaf rises, along with the feed, after which it all collapses. Humans and babies mast to unfamiliarity as they fall, smoking down a bottomless hole, down, down. McDonald's turned into Dante's hell. We are far from Abuster and criticism of capitalism; it's horror.

But where did the art of painting come from? The few paintings on the exhibit look more like collage or comments on previous painters. Collections of things and fragments accompany most pavilions. For example, the Indian who tells the story of Mahatma Gandhi through collecting things, bone prostheses, Hindu chains, plows etc. More radical is Filipino Mark Justinianis Island Weatherwho, in an at once free-floating and underground gigantic installation of a box set full of strange things and objects, records the Philippine archipelago from a recognizable territory to a new enchanting earth. Staggering and cosmic.

Disaster and collapse

In the one room of the Giardini Pavilion has Teresa Margolles (Mexico) with Ciudad Juarez Wall exhibited a piece of concrete mortar from a public school in Ciadad Juárez (a border town known for the drug war and countless innocent victims) – with barbed wire fencing above and bullet holes all around. Re-installing the wall of the Biennial makes an impression, not least in light of Trump's xenophobic demands for a wall to separate the United States and Mexico.

In the room next door has the Chinese Sun Yan og Peng Yu with theirs Can't Help Myself placed a giant installation in a closed cube, a five meter long robotic arm that ends in a bucket. Around the floor of a circle is a thick liquid dark red liquid. As the machine restlessly bends back and forth in the transparent "cage", it immediately gives the impression of an industrial robot by an assembly line. But then it is as if it is starting to dance with its arm, "shaking its ass," while alternately shoving the blood-like fluid back into place in a sisyphoid-like motion. At one and the same time, creepy and poetic, and as we stand there watching for the second time, it comes to us: It's a dinosaur – a carnivorous Tyrannosaurus rex!

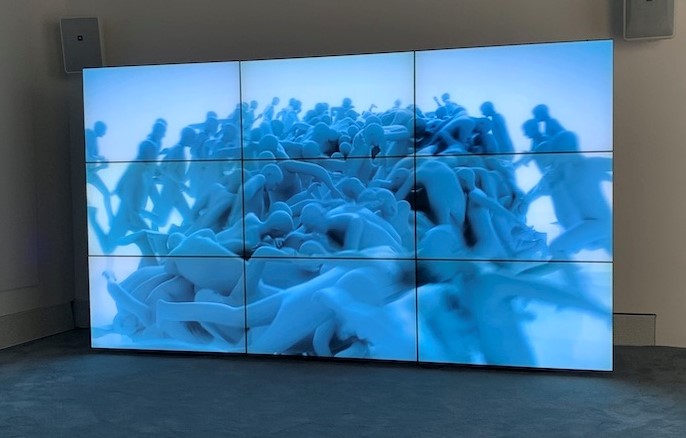

Next I see --Jon Rafmans Disaster under the Sun., where a group of digitized human-like dolls tumble around in an undefined landscape. After a while, they are pushed beyond the edge, pressed down into the crevices of the earth and away. Rafman asks questions like: What happens when man is no longer the center? Who are we and what are we made of? And is the collapse of time purely a consequence of climate and refugee conditions, or is it part of a broader discussion of what has happened to our civilization?

Thoughtfully, the climate issue at this year's biennial is not elevated to an independent theme, but part of a much broader reflection on what it means to be human in a new-technological age. AI and speculative fiction. For example, works exploring AI as a self-generating brain (Yusifova, Azerbaijan), as total control (China!), As future utopia (Hito Steyerl This is the Future).At Steyerl Milestone one moves among digital flowers whose sensuous shapes and colors dissolve on the screen in an algorithmic fantasy. The film explores the question of whether AI can predict the future and the answer is no. Technology is a false hope, AI can only shed light on what is growing out of pre-existing forms. Maybe because it is not a real sensory experience?